Three years after the creation of the Artemis Accords, after months of silence on the topic, India became a signatory to the international US-led initiative to work together with other countries on space exploration and research on 21 June 2023, bringing total sign-ups to-date to 27 nations. But why did India do this, what was in it for the USA and why did it happen now?

India’s signing of the Artemis Accords came only days ahead of the launch of the nation’s Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft with an orbiter, lander and a rover, which arrived at the Moon in late August and, if the mission is successful, makes India only the fourth country to achieve a lunar soft landing.

The name (in Greek mythology Artemis was the twin sister of Apollo) and the underlying intent of an international, peaceful and sustainable future in space, was originally inspired by the fictional Star Trek television series in which the ‘Khitomer Accords’, signed in 2293, secured peace between the Federation and the Klingon Empire.

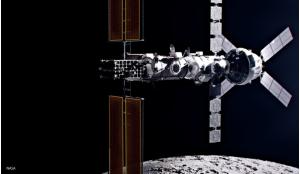

The Artemis Accords framework is associated with the Artemis Program, a US-led endeavour to return humans to the Moon by 2025. Unlike the Apollo missions of the 1960s and 1970s, the Artemis Program is international from the outset with a strong contribution from the private sector.

The Artemis Accords framework is a non-binding bilateral agreement established by NASA and the USA State Department. Ostensibly consistent with the United Nations 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST) but entirely independent of it, they specify 10 principles for international cooperation in the civil exploration of the Moon, Mars, comets and asteroids. They were announced on 13 October 2020 during the 71st International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Dubai.

The initial eight countries (Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States) have gradually grown and on 22 June 2023, India brought the total to 27 countries.

Partnership

The Accords require all signatories to abide by a number of principles when operating in space. The 10 principles are:

- 1. Peaceful uses: cooperative activities are exclusively for peaceful purposes and in accordance with international law.

- 2. Transparency: commit to broad dissemination of information regarding their national policies and exploration plans. Agree to share scientific information with the public on a good-faith basis consistent with Article XI of the Outer Space Treaty (OST).

- 3. Interoperability: agree to develop infrastructure to common standards for space hardware and operating procedures that include fuel storage, landing systems, communication, power and docking interfaces.

- 4. Emergency Assistance: commit to offering all reasonable efforts to render assistance and comply with the rescue and return agreement as outlined in the Outer Space Treaty.

- 5. Registration of Objects: registration of space objects (on the surface, in orbit or in space) by signatory nations can help to mitigate risk of harmful interference.

- 6. Release of Scientific Data: commit to open sharing of scientific data arising from space exploration missions. Not mandatory for private-sector operations.

- 7. Preserving Outer Space Heritage: undertake to ensure new activities help preserve and do not undermine space heritage sites of historical significance.

- 8. Space Resources: signatories affirm that extraction of resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the Outer Space Treaty.

- 9. Deconfliction of Space Activities: undertake exploration with due consideration to the United Nations guidelines for the long-term sustainability of outer space activities as adopted by the UN Committee for Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) in 2019. Activities, where potential harmful interference could occur, should be restricted to pre-identified ‘Safety Zones’. The size, location and nature of operations in a Safety Zone should be notified to all signatories and the UN Secretary-General.

- 10. Orbital Debris: signatories agree to limit harmful debris in orbit through mission planning that includes selecting flight orbital profiles that minimise conjunction risk, minimising debris release during the operational phase, timely passivation and end-of-life disposal.

Mutually beneficial

Why would countries want to sign up to the Accords? The current and next decade will see multiple nations arriving at the Moon, near-Earth asteroids and comets for space exploration and commercial exploitation. The Accords define a set of guidelines, principles, and a common norms and behaviours that are mutually beneficial when operating missions far from Earth.

But why not simply sign up for the Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Treaty?

While the Outer Space Treaty, established in 1967, has 113 signatories, only 18 parties have agreed to be bound by the Moon Treaty (1979). India is one of those 18 but has not yet ratified it.

Why have so few nations signed up to the Moon Treaty? It is all to do with the legal status of extracting resources from the Moon. Article I of the OST describes outer space, which includes the Moon and other celestial objects, as being the “province of all mankind” and “not subject to national appropriation”.

Further, article II in the Moon Treaty explicitly forbids any part of the Moon from becoming the property of a nation, a private organisation or a person. Countries don’t sign up to the Moon Treaty because they consider it will restrict their future commercial operations in space and especially on the lunar surface.

Resource extraction

The Artemis Accords ostensibly offer a workaround by affirming that extraction of resources “does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the OST.” In other words, you can extract and own the resources but have no claim of ownership of the place from which they came. How legally robust that is only time will tell but the Artemis Accords already has many more signatories than the Moon Treaty.

There is another reason why nations may join the Artemis Accords. As the name suggests, Artemis Accords signatories can join the already international, ‘Artemis Program’. What that actually means for each nation will depend on the capability each nation brings to the table.

Even small nations, like new entrants Romania and Rwanda that have minimal capability will have access to and opportunities for cooperation. A key benefit of any club membership is access to other members of the club.

Competition

Why has India waited until now to join? One answer is that the Artemis Accords have a competitor. In March 2021 Roscosmos and the China National Space Administration (CNSA) announced the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), a planned lunar base designed for conducting scientific research. It will include all support facilities on the lunar surface and in lunar orbit and transport between Earth and the Moon and is “open to all interested countries and international partners.”

Two years on, only Pakistan and the UAE have joined China and Russia. India has a long history of cooperation in space with both the USA and the USSR/Russia. It has always remained non-aligned but has pragmatically pivoted to wherever its interests were best served at the time. India’s first rocket, launched into space in 1963, came from the USA. Its first satellite and first astronaut went to Earth orbit on Soviet launch vehicles.

Over the last five years, Russia has been assisting ISRO with its Gaganyaan (Human Spaceflight) programme. However, sanctions imposed on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine have severely diminished its space capabilities. Right now, and in the foreseeable future, India sees more opportunities with the USA than with Russia.

The geopolitical and economic landscape of mid-2023 was just right for the USA to invite India and for India to accept. It was in the USA’s interest to get India onboard. The more countries sign up for the Accords, the closer they get to becoming a de facto standard.

Benefits for India

Recognising the importance to the USA of India signing the Accords, India was well placed to extract significant concessions that included space and non-space related benefits including:

- a NASA/ISRO joint mission to the ISS in 2024 (this does not necessarily imply that an Indian astronaut will visit the ISS in 2024 but support for its Gaganyaan mission is likely included)

- support India’s membership of the Mineral Security Partnership: establish a joint Indo-US mechanism between industry, government and academia for artificial intelligence, information science and quantum information.

- a new public-private cooperation forum for the development of advanced communication using 5G and 6G

- a multimillion-dollar investment to establish a semiconductor ecosystem which will include semiconductor assembly and test facilities in India.

In addition to collaborative activities in space, and bilateral economic opportunities, perhaps the most significant concession was the four-day state visit by India’s Prime Minister to the USA and the opportunity to address a joint meeting of the US Congress. An important vindication from the president of the most powerful democracy to the prime minister of the largest one. Particularly useful for a prime minister looking to win a third term in elections in 2024.

India’s membership boosted the future success of the Artemis Accords and the Artemis Program. However, the Accords are not legally binding. They do not form a treaty or agreement and there is no compliance or enforcement mechanism.

China

The principles of the Accords are said to be “grounded” in the OST and the Moon Agreement, but the Accords are not a United Nations product but a product of the US State Department and NASA.

Despite the Accords having their roots in one country, currently they are the only framework that can offer practical value and tangible benefits to all nations with space missions beyond Earth. In the USA, the Wolf Amendment (2011) legally restricts how NASA can collaborate with Chinese space missions. While the Wolf Amendment does not legally prohibit China from signing the Accords, in practice that is the effective outcome.

Over the last decade, China checked off some astonishing accomplishments in space. A highly successful human space programme, a space station in Earth orbit, a lunar rover on the far side of the Moon and a soft landing of a rover on the surface of Mars.

China sees the Artemis Accords as an instrument to sustain US dominance while undermining China’s space ambitions. All this while Russia’s space programme has experienced a significant decline resulting from the sanctions following its invasion of Ukraine. Russia may be associated with the heady days of Sputnik and Gagarin but now China has surpassed Russia and is second only to the USA.

Whilst the Wolf Amendment remains, it is unlikely in the short term that China will join and it may thus prevent the Artemis Accords from being adopted as a global framework for responsible behaviours in space.

Just as in Star Trek, the Khitomer Accords of 2293 were followed by the Second Khitomer Accords in 2375, so as the Artemis Accords attain wider engagement over time, they too will need to develop. The existing Artemis Accords should be considered only as an initial starting point.

The Accords will evolve as an increasing number of countries and businesses take exploratory steps beyond Earth orbit. That the Artemis Accords is a product of one country, the USA, is its major drawback. To succeed in its ambition to be a global “common set of principles to govern the exploration and use of space” the Artemis Accords require a significant political transformation. In a decade or two when the Artemis Program exists only in the rear-view mirror or history, it could finally become the global governance framework for all nations exploring and exploiting space beyond Earth orbit. The framework in essence would be identical, but politically transformed with a new name and placed under the auspices of the United Nations. That is a real possibility albeit a remote one at the present.

About the author

Gurbir Singh is a UK-based cyber security consultant and non-fiction writer specialising in space. He studied science and computing and holds a science and an arts degree. He was one of 13,000 unsuccessful applicants responding to the 1989 advertisment, ‘Astronaut wanted. No experience necessary’, to become the first British astronaut. Helen Sharman was eventually selected and flew on the Soviet space station Mir in 1991. Gurbir holds a private pilot’s licence for the UK, USA and Australia. He is the author of several books including The Indian Space Programme (Astrotalkuk Publications, 2017).