Within the coming decade, organisations – both public and private – from various countries will carry out operations on the Moon. The infrastructure that allows them to do this will be vital and, in this article, Michael Castle-Miller presents the Lunar Development Cooperative as a potential solution that would allow them to all work cooperatively and mutually benefit from the Moon’s resources.

The settlement of the Moon, and space more broadly, will be one of the most transformative steps in the history of our species. Ultimately it has the potential to transform our relationship with Earth by moving much energy production, mining and heavy industry off the planet, allowing us to greatly slow the effects of climate change and restore biodiversity. It will also transform the way we think about our own humanity and shared responsibility to each other and to nature, if phenomena like the overview effect are any indication. The future of Earth depends on our future in space.

The frameworks we establish now to support the settlement of space will have an incalculable effect on whether and how this transformation takes hold in future generations. Service delivery is a crucial component to these frameworks. If services are either unaffordable or exclusive, then space may become the province of only a few rich and powerful individuals and nations, and we will fail to realise the full benefits space offers.

The key to making services for space settlement affordable and inclusive lies in effectively channelling the economic rents resulting from activities in space. ‘Economic rents’ are increases to a person’s wealth that are caused by other people’s productive activities, rather than by the efforts of the person whose wealth grows. On Earth, if a city builds good infrastructure, schools and services in a neighborhood, property will increase in value, making the owners there the beneficiary of economic rents. They did not earn this extra wealth, but they can cash in anyway.

Future lunar infrastructure supporting living and working on the Moon.

Future lunar infrastructure supporting living and working on the Moon.

Economic literature suggests that this sort of unearned income is enormous in society and that, unless redirected, it mostly goes to the already well-off. Space will be no different. A thriving society of industries and communities on the Moon will generate huge increases in economic rents that, in the long run, will be more than enough to repay - and generate a dividend on - the investment in services to support that society. The challenge is to channel economic rents toward these services rather than toward those who do not earn them.

A way forward

Any individual on Earth could become a shareholder with a minimum investment threshold affordable by global standards

The Lunar Development Cooperative (LDC) is one model for doing this. It would be an organisation that finances and delivers affordable and value-generating public services through location-based service-access fees. These fees would not only enable the LDC to provide services but incentivize it to maximise the environmental, social and economic wellbeing of the Moon.

The LDC does not require an international treaty or regime to get started but instead can evolve from the bottom up and adapt to changing circumstances. It supports the existing 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST), helping prevent territorial appropriation of the Moon and promoting international cooperation. It also aligns well with recent laws and initiatives promoting the commercial use of space, such as the Artemis Accords. As a voluntary cooperative, membership would be open to anyone. Moreover, the LDC’s revenue model imposes no economic cost – neither on lunar or Earth-based parties – because its revenue would come only from the value the LDC creates.

In the early years, the LDC would be the equivalent of a mining town, supporting and managing the development of resources on the Moon. Later, it would grow to support large, thriving cities.

By utilising private and public-sector investment capital, the model would be structured as a public-private partnership corporation in which 51 percent or more of the voting power is held by diverse, non-state investors and 49 percent or less by governments from around the world. Countries would not need to redirect scarce funds from their annual budgets to take part. They could, instead, use their investment capital, such as from sovereign wealth funds, since the LDC generates a return on investment. Limitations on how much voting power any one public or private investor has would prevent capture by the narrow political or commercial interests of any one particular shareholder.

Under the plan, developing countries would be able to invest in space as shareholders in the LDC. Stock options might enable participants to achieve a larger share in the cooperative than they could otherwise afford in the near term.

In principle, any individual on Earth could become a shareholder with a minimum investment threshold affordable by global standards. There would also be mechanisms for participation of indigenous peoples, including through an LDC Board of Advisors, to help guide decisions and provide accountability.

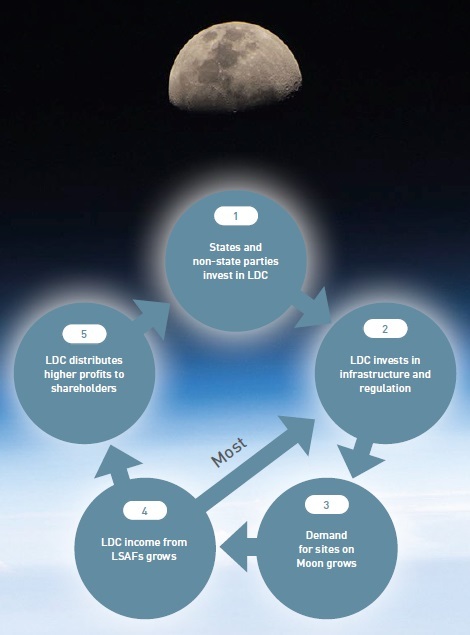

LDC Virtuous Cycle - smart investments in public services on the Moon lead to increased revenue for the LDC. Most of this revenue is re-invested in still further improvements to services (which increases revenue further), and the rest results in a return for investors, which in turn mobilises more investment.

LDC Virtuous Cycle - smart investments in public services on the Moon lead to increased revenue for the LDC. Most of this revenue is re-invested in still further improvements to services (which increases revenue further), and the rest results in a return for investors, which in turn mobilises more investment.

The LDC’s business model is structured so that it generates profit in proportion to the overall well-being and value of the lunar economy, society and environment it helps create. This gives it a strong incentive to invest and manage its services in ways that promote the responsible and inclusive use of the Moon.

To support lunar development, the LDC would make continual investments in the quality of infrastructure and services

Both state and private parties from any nation can benefit from LDC services by becoming members of the cooperative. Membership would include service-access licenses for the locations of the Moon members decide to use, which entitle the members to receive a bundle of LDC services at their chosen locations.

Members would be contractually obligated to not interfere with other members at other locations. This obligation would effectively establish safe zones and help with the development of international norms of non-interference and shared use. It would be enforced through sensible regulation and infrastructure (such as protective berms around launch pads), as a value-added service for members.

To support lunar development, the LDC would make continual investments in the quality of infrastructure and services. These investments would lower the cost and technical barriers to reaching and operating on the Moon. Lowered barriers, in turn, would stimulate demand for service-access licenses, especially at locations where the LDC delivers its best services. Development will then likely cluster into settlements or cities where shared services can be delivered most efficiently.

Service access license fees

Members can select how long they would like the service access license for a particular site to last, with terms up to 40 years. Each of these years would have a fee associated with it. The fees for the initial 5-10 years would be set at close to zero. After that initial period, however, the fee would gradually rise in proportion to the estimated growth in market demand for LDC services at that particular site.

Each time a license expires, the fees for subsequent years would be re-adjusted to the estimated market values for those years. If the area is remote from LDC infrastructure or has fewer attractive natural characteristics, the rate would remain very low. Licenses at better serviced, more desirable locations would have much higher rates.

There are several possible ways of determining the market rate for each year of a license. The best approach is not yet clear because it is unknown how much market data will exist at this point. However, it is possible to describe the approach under two different scenarios.

First, LDC members are allowed to sell the remaining years of their license to other members. If there are many such transactions of licenses, it may be possible to use these transactions as a basis for an estimate. For instance, if there is a thriving ecosystem of startup lunar enterprises, there may be a high failure rate. In this scenario, many initial license holders would, after going under in five or 10 years, sell the remaining years of their license to another party, enabling the new license holder to access LDC services at the site until the term expires. With enough such transactions, there may be sufficient data to reliably estimate the appropriate fee for many of the licenses when they enter the next license term.

On the other hand, if there aren’t many transactions, a few options exist for determining a market rate based on the member’s own, self-assessment of value. One such approach would be to set the rate by auction. In an auction, all parties who wish to utilise the services at the site will submit bid schedules that set out what they are willing to pay in fees for each year of the license. These payments would likely rise over time if the users expect the sites to become more useful over the years.

The highest bid would be based on the net-present value of the sum of payments. If the existing license holder wants to hold onto the license and continue receiving LDC services at the site, the license holder would bid in this auction, perhaps receiving a 10 percent discount relative to the highest bid.

A future lunar base.

A future lunar base.

Avoiding coercion

There are plans to create LDCs at experimental space habitats in various locations

The LDC would not be a landlord, but a service provider. It wouldn’t claim to own areas of the Moon and force occupants to pay rent for being there. Instead, it would charge license holders for the right to access its services.

So, in theory, a person without an LDC license might utilise a site, choosing not to use the cooperative’s infrastructure or services. If this happens, the LDC could not force that person out of the site or use other coercive measures. This restriction on coercion forces the LDC to stay competitive and prevents abuse of power.

That being said, there is a real risk that these non-license holders could interfere with the ability of license holders to use sites effectively, since they would not be bound to the same contractual obligations of non-interference as license holders.

To address this possibility, there are a number of strategies that could be adopted to mitigate the potential problem, such as:

- Offering services that reduce the costs of operating on the Moon so much that they are widely considered indispensable, so almost everyone becomes an LDC member

- Concentrating services early in high-demand areas of the Moon (north and south poles, nadir points below L1 and L2, major lava tubes, etc.) so they become at least locally indispensable

- Not building infrastructure near places that are already utilised by non-LDC license holders.

- Working towards the adoption of international norms of non-interference on the Moon so that parties that do not have LDC licenses at least do not interfere with LDC customers.

Why it works

The critical component of this model is reliance on location-based service access fees (LSAFs) for revenue. LSAFs are the annual fees members pay for their service-access licenses.

Since LSAFs are driven by the level of demand the LDC’s services create at particular sites, they will grow dramatically relative to the cost of service provision the easier it becomes to operate on the Moon. LSAFs have far greater long-term return-generating potential than if the cooperative were to simply charge separate usage fees for its services. An example could be drawn from infrastructure projects in the US like the Erie Canal and the Trans-Continental Railroads. These projects had a far greater long-term financial impact on demand for space in New York City and the American West, respectively, than they ever could have ever earned from freight or passenger fees alone. The LDC would use the demand it generates at locations on the Moon, rather than usage fees, to fund the infrastructure to get there.

One example of an LDC prototype would be simulated space habitats on Earth

Therefore, once its short-term revenue needs are satisfied, the LDC will increasingly lower its prices for individual services and rely almost exclusively on LSAFs for revenue. It will, for instance, provide some services at cost price or make them completely included in the LSAF. This approach helps lower the barriers to operating on the Moon as much as possible, which both benefits the LDC’s bottom line by further stimulating demand and helps promote important global aims like more inclusive access to the Moon.

As a policy matter, LSAFs are the most economically efficient form of revenue to support lunar public services. LSAFs effectively only collect a portion of the value that the LDC itself creates through its services, not value created by lunar occupants themselves. They are not a tax and therefore do not diminish economic productivity or take away the value that people earn on the Moon. Rather, they finance public services with money that would have resulted in economic rents for lunar occupants.

The LSAF approach also strongly aligns the LDC’s incentives with the overall well-being of wthe lunar society and environment. LSAFs will tend to rise or fall in proportion to the quality of services the LDC provides and overall conditions on the Moon. In other words, a deteriorating lunar environment, society or economy will greatly reduce demand for service access licenses, thus harming the cooperative’s revenue. Conversely, thriving and healthy conditions will raise demand, boosting LDC revenue.

An advanced future lunar base as envisaged by artist James Vaughan.

An advanced future lunar base as envisaged by artist James Vaughan.

Next steps

To get this paradigm-shifting model up and running, a Lunar Development Cooperative Working Group has been established. Members of the group will be involved in delivering various initiatives that ultimately lead to creating a prototype of the cooperative here on Earth; and this will help ascertain what works and what needs to change.

One example of an LDC prototype would be simulated space habitats on Earth that provide a supporting framework and common-use services that enable both commercial activities and scientific research. Another prototype idea is a multi-player online game that simulates the LDC model to test how players would act as different types of participants (or non-participants) in the LDC.

Finally, steps are being taken toward formally creating the LDC. This includes research and development on the initial techniques for delivering power and other services on the Moon. It is anticipated that this technology will be rolled out through a power station and multi-use base at a location on the Moon for use by LDC members.

About the author

Michael Castle-Miller is a governance consultant who has served as an advisor to governments, international organisations, civil society and private investors in over 25 countries. He specialises in the legal and public policy frameworks for special economic zones and new cities that serve as experiments in reforms. He is the Founder and CEO of Politas Consulting, which provides innovative legal and policy solutions to help cities and special jurisdictions achieve inclusive growth. He is also co-creating the Lunar Development Cooperative Working Group.