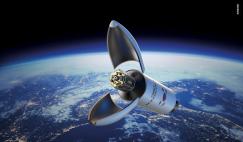

ESA’s Cheops mission lifted off on a Soyuz-Fregat launcher from Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, at 09:54:20 CET on 18 December on its exciting mission to characterise planets orbiting stars other than the Sun.

Signals from the spacecraft, received at the mission control centre based at INTA in Torrejón de Ardoz near Madrid, Spain, via the Troll ground tracking station at approximately 12:43 CET confirmed that the launch was successful.

Cheops, the Characterising Exoplanet Satellite, is a partnership between ESA and Switzerland, with important contribution from 10 other ESA Member States. ESA’s first mission dedicated to extrasolar planets, or exoplanets, it will investigate known planets beyond our Solar System and provide key insight into the nature of these distant, alien worlds.

Scientists had long speculated about the existence of exoplanets until the discovery of 51 Pegasi b, the first planet found around a Sun-like star, which was announced in 1995. The discoverers, Didier Queloz and Michel Mayor, shared the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics for their breakthrough finding, which marked the beginning of a new era of investigation and turned exoplanet research into one of the fastest growing areas of astronomy.

Over the past quarter of a century, astronomers using telescopes on Earth and in space have discovered more than 4000 exoplanets around stars near and far, most of which have no counterparts in our Solar System. This widely diverse assortment extends from gassy worlds larger than Jupiter to smaller, rocky planets covered in lava, with the most abundant exoplanet type found in the size range between Earth and Neptune.

“Cheops will take exoplanet science to a whole new level,” says Günther Hasinger, ESA Director of Science.

“After the discovery of thousands of planets, the quest can now turn to characterisation, investigating the physical and chemical properties of many exoplanets and really getting to know what they are made of and how they formed. Cheops will also pave the way for our future exoplanet missions, from the international James Webb Telescope to ESA’s very own Plato and Ariel satellites, keeping European science at the forefront of exoplanet research.”

Cheops will not focus on the search for new planets. Instead, it will follow-up on hundreds of known planets that have been discovered through other methods. The mission will observe these planets exactly as they transit in front of their parent star and block a fraction of its light, to measure their sizes with unprecedented precision and accuracy.

Cheops measurements of exoplanet sizes will be combined with existing information on their masses to derive the planet density. This is a key quantity to study the internal structure and composition of planets and determine whether they are gaseous like Jupiter or rocky like Earth, whether they are enshrouded in an atmosphere or covered in oceans.

“We are very excited to see the satellite blast off into space,” says Kate Isaak, ESA Cheops project scientist.

“There are so many interesting exoplanets and we will be following up on several hundreds of them, focusing in particular on the smaller planets in the size range between Earth and Neptune. They seem to be the commonly found planets in our Milky Way galaxy, yet we do not know much about them. Cheops will help us reveal the mysteries of these fascinating worlds, and take us one step closer to answering one of the most profound questions we humans ponder: are we alone in the Universe?”

For some planets, Cheops will be able to reveal details about their atmosphere including the presence of clouds and possibly even hints of the cloud composition. The mission also has the capability to discover previously unknown planets by measuring tiny variations in the timing of the transit of a known planet, and can also be used to search for moons or rings around some planets.

Cheops is the first ‘Small’-class mission implemented in the Cosmic Vision 2015–25 programme, the current planning cycle for ESA's space science missions, and the first mission in the programme overall to be launched. As a Small-class mission with a relatively short time – only five years – from project start to launch, it entailed several challenges, making it necessary to use technologies that have already been tried and tested in space, and driving several aspects of the satellite design.

“Both Cheops instrument and spacecraft are built to be extremely stable, so as to measure the incredibly small variations in the light of distant stars as their planets transit in front of them,” says Nicola Rando, ESA Cheops project manager.

“For a planet like Earth, this amounts to the equivalent of watching the Sun from a distant star and measuring its light dim by a tiny fraction of a percent.

“Now we are looking forward to the first part of the operational activities, making sure that the satellite and instrument perform as expected, ready for scientists to perform their world-class science.”

Cheops shared the ride into space with the Italian space agency ASI’s Cosmo-SkyMed Second Generation satellite, which separated 23 minutes after liftoff.