using the Okayama Astrophysical Observatory, Xin-glong Station, and Australian Astronomical Observatory. The central star known as HD 47366 is larger than the Sun (1.8 solar masses) and is classified as a K1 giant (compared with the Sun which is classified as a G2 star). It is also of solar metallicity meaning that is has the same chemical composition as the Sun.

The planets in question are also on the large side - nearly twice the mass of Jupiter and the two are thought to have an orbital period ratio slightly smaller than 2. Planetary orbits are often characterised according to their mean-motion resonance, which can give an indication as to the stability of the system in question. These resonances most probably arise from evolutionary processes as migrating planets forming in the protoplanetary disc become trapped. In our Solar System for example, it is known that Neptune and Pluto have a 3:2 resonance, meaning that Neptune will orbit the Sun three times in the same time that it takes Pluto to orbit the Sun twice.

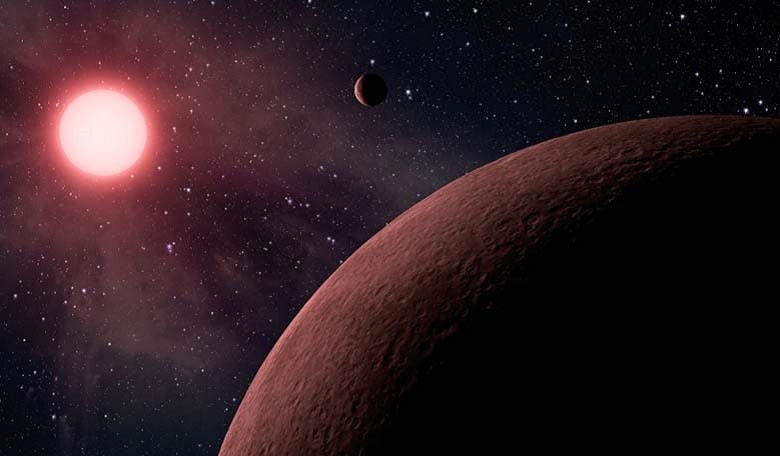

The discovery, while not unique, is relatively uncommon in exoplanet detections as relatively few multiple planetary systems have been found around evolved giant stars so far. It is the multipleplanet systems around ageing stars that are of particular interest in terms of formation and evolution, as one day our Sun will evolve to be a red giant.

The authors of the paper state, that to date, radial-velocity surveys have discovered about 120 substellar companions around such evolved stars and that interestingly, almost all of the giant-planet pairs (with period ratios smaller than 2) are preferentially found around evolved intermediate-mass stars. The reason for this is unclear, however, it could simply be a product of stellar evolution, whereby mass-loss from the evolving central star disrupts the planetary orbits causing them to migrate outwards. It is also possible that the star might have harboured a third planet that was engulfed as the star expanded, causing the current orbital configuration of the remaining stars - a scenario that may one day shape the orbit of planets in our own Solar System.

The researchers who have discovered the double-planet system state that although it is likely that that both of the planets have nearly circular orbits, it is not known if the orbits of the planets are stable. Planetary systems with near circular orbits have better chances of survival because in these configurations, the bodies might interact gravitationally, but at any epoch they will be distant enough to not get too close to their neighbours to cause significant disruption.

The number of multi-planet systems found to date, regardless of the central star’s status is around 506 systems and about 280 of these have only two confirmed exoplanets. Taking into account the strong bias against low-mass and/or long-period planet detection, and the increased difficulty of fully characterising systems with more than one planet, the number of known multi-planet systems is certainly still a lower limit. It is suggested that a higher fraction, if not the majority of planets detected around stars are likely to be part of a multi-planet system rather than isolated, single planetary companions, as is often found.

The different techniques for detecting extrasolar planets shows that planetary systems appear to be very frequent in all kinds of stable configurations, with systems found to orbit around stars with different ages, including binaries and even pulsars. Nevertheless, multiple planetary systems around evolved giants, appear to account for a very small fraction of the planets detected so far. The

Further information on the discovery can be read here www.arxiv.org.