Scientists from the U.S. and Taiwan have captured the first clear image of an accretion disk around a young star. According to most commonly accepted theories, young stars feed on accretion disks as they grow. The disk may also make up the material that would eventually turn into planets. The image captured by the ALMA radio telescope in Chile is the first clear image of an accretion disk – earlier technology was not able to obtain clear images. ALMA was able to zoom in on a star named IRAS 05413-0104, part of a system believed to be just 40,000 years old, and take an image of its rotating accretion disk.

ALMA, the most expensive radio

telescope ever built, was completed only four years ago, and has

since steadily provided clear-resolution images of unprecedented

quality. This new image of the accretion disk disproves the theory

that the magnetic core of a young star would prevent the accretion

disk from spinning and therefore prevent its ability to gather matter. The image clearly shows that the disk is, indeed, spinning.

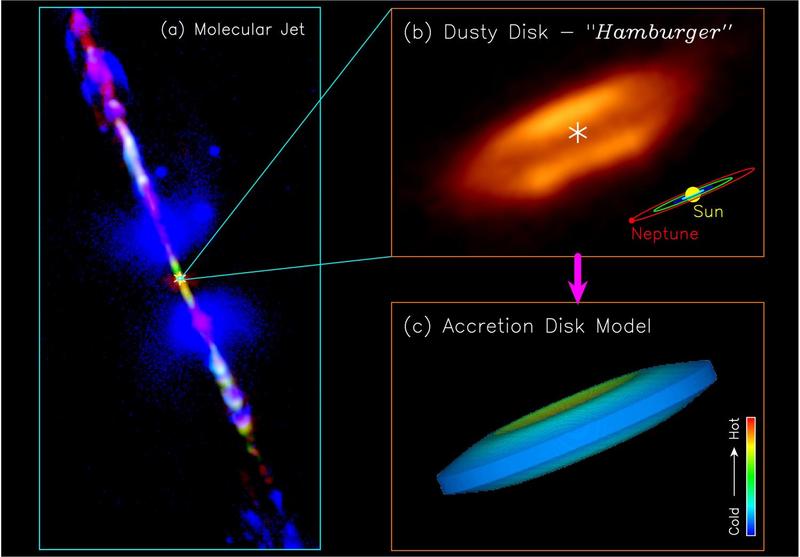

Jet and disk in the HH 212 protostellar

system: (a) A composite image of the jet, produced by combining

images from different telescopes. The orange image around the center

shows the accretion disk at 200 AU resolution. (b) Close-up of the

center of the dusty disk at 8 AU resolution. Asterisks mark the

possible position of the central protostar. A dark lane is seen in

the equator. Our solar system is shown in the lower right corner for

size comparison. (c) An accretion disk model that can reproduce the

observed dust emission in the disk. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Lee

et al.

Jet and disk in the HH 212 protostellar

system: (a) A composite image of the jet, produced by combining

images from different telescopes. The orange image around the center

shows the accretion disk at 200 AU resolution. (b) Close-up of the

center of the dusty disk at 8 AU resolution. Asterisks mark the

possible position of the central protostar. A dark lane is seen in

the equator. Our solar system is shown in the lower right corner for

size comparison. (c) An accretion disk model that can reproduce the

observed dust emission in the disk. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Lee

et al.

Accretion disks are most likely made of silicate, iron, and other interstellar matter. Due to their triple-layer appearance, the research team has described the accretion disk as very similar to a hamburger.

The complete

study of the accretion disk image, “First detection of equatorial

dark dust lane in a protostellar disk at submillimeter wavelength”,

was published in Science Advances on April 19, 2017.