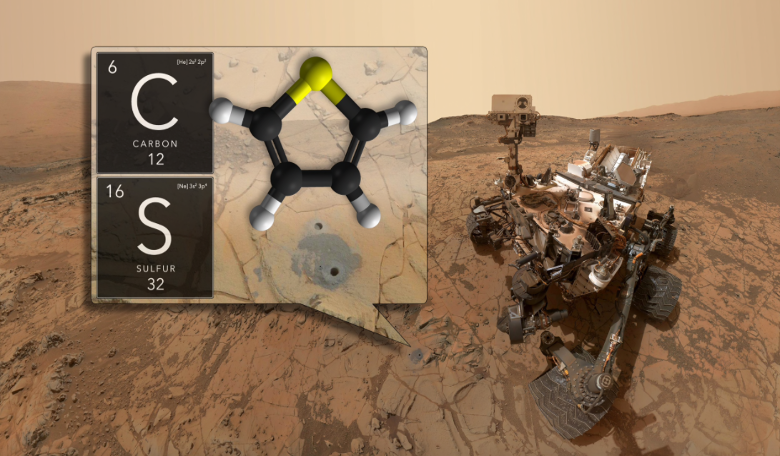

The Curiosity rover which is currently trundling around the Gale Crater has found organic material in samples of mudstone, that once upon a time sat at the bottom of an an ancient lake. Coupled with new evidence of seasonal methane variations in the martian atmosphere, these new findings are an hopeful indicator that life might have once survived on the Red Planet.

The organic material was unearthed in 3-billion-year-old sedimentary rock samples extracted by Curiosity’s Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument suite and then heated to 500 degrees Celsius to release its molecular constituents.

SAM found a number of compounds in the samples including sulphur, carbon, thiophenes, benzene, toluene, and small carbon chains, such as propane or butene. Thiophenes are the simplest sulphur-containing aromatic compounds (aromatic refers to how the molecules are bonded together) and it occurs with benzene in coal tar.

Carbon, which is the primary ingredient of coal was also found to be in roughly the same quantities as those observed in Martian meteorites found on Earth, and about 100 times greater in concentration than prior detections of organic carbon on Mars' surface.

While the discovery is one of the most tantalising searches yet to indicate that biological processes were (or maybe still are) responsible for these organic materials, it is not definitive proof of life on Mars.

"Curiosity has not determined the source of the organic molecules," said Jen Eigenbrode of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who is lead author of one of the two new Science papers. "Whether it holds a record of ancient life, was food for life, or has existed in the absence of life, organic matter in Martian materials holds chemical clues to planetary conditions and processes."

Looking not just to the ground for answers, scientists have also been studying the Red Planet’s tenuous atmosphere for clues and have found seasonal variations in methane levels around the Gale Crater region.

The study, which has been in place for around six years (the equivalent of nearly three martian years), shows that low levels of methane within the crater repeatedly peak in warm, summer months and drop in the winter every year. This in stark contrast to previous detections which showed large, unpredictable plumes deposited in the atmosphere.

"This is the first time we've seen something repeatable in the methane story, so it offers us a handle in understanding it," said Chris Webster of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, lead author of the second paper. "This is all possible because of Curiosity's longevity. The long duration has allowed us to see the patterns in this seasonal 'breathing.'"

Again, while water-rock chemistry might have generated the methane, scientists cannot rule out the possibility that the gas was produced by biological processes. "Are there signs of life on Mars?" said Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA's Mars Exploration Program, at NASA Headquarters. "We don't know, but these results tell us we are on the right track."