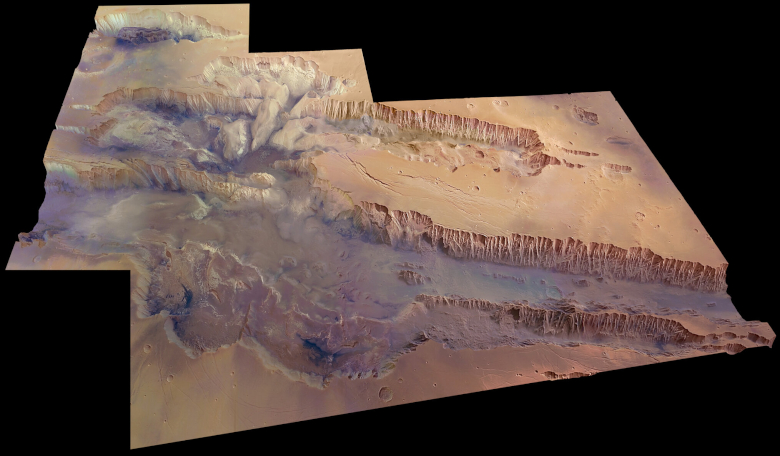

The ESA-Roscosmos ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), which has been searching for signature gases in the Martian atmosphere since 2016, has spotted significant amounts of water at Valles Marineris; a 4000 km (2500 mile) long canyon system that runs along Mars’ equator.

The water, ESA says, lays hidden in the uppermost metre of Mars’ soil and covers an area about the size of the Netherlands and stretches as far Candor Chasma, a deep valley in the northern part of Valles Marineris.

“The reservoir is large, not too deep below ground, & could be easily exploitable for future explorers” ESA say via Twitter.

This water-rich region was found by the TGO’s FREND instrument. FREND, which stands for Fine Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector, is designed to map hydrogen on the martian surface down to a metre deep to help reveal deposits of water-ice near the surface.

“With TGO we can look down to one metre below this dusty layer and see what’s really going on below Mars’ surface – and, crucially, locate water-rich ‘oases’ that couldn’t be detected with previous instruments,” says Igor Mitrofanov of the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, Russia and principal investigator of FREND.

According to Mitrofanov, who is also the lead author of the new study detailing this research, as much as 40 percent of the near-surface material in the colossal Valles Marineris canyon system appears to be water. This is based on the assumption that the hydrogen seen by FREND is bound into water molecules, he adds.

How those water molecules are stored though still remains debatable, and so far there are two main contenders; they could either be partially associated with chemically bound water of hydrated minerals or they could be held as subsurface water ice. This is much like Earth’s permafrost regions, where water ice permanently persists under dry soil because of the constant low temperatures.

Chemically bound water is observed in many spots on the martian surface by near infrared spectrometers from orbit, whereas water ice, the most abundant form of water deposits found on Mars, is generally detected at the planet’s frigid polar regions.

Like Earth, Mars’ equator is warmer than at the poles, so water ice is not expected to exist near the surface here as temperatures are not cold enough for it to remain to be stable – instead it usually evaporates.

However other observations suggest that minerals seen in this part of Mars typically contain only a few percent water, much less than is evidenced by these new observations, says Alexey Malakhov, also of the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

As such, the team think the water more likely exists in the form of ice, says Malakhov, but for it be present in such large volumes, some special, as-yet-unknown mix of conditions must be present in Valles Marineris to preserve the water – or that it is somehow being replenished.

At ten times longer and five times deeper than Earth’s Grand Canyon, Valles Marineris is arguably one of Mars’, and perhaps the Solar System’s, most dramatic landscape.

Mitrofanov and colleagues suggest that it could be due to very special geomorphological conditions within the canyon that is preventing the water from escaping. It could also be accumulating even now due to the condensation of sparse water vapour from the atmosphere.

“This finding is an amazing first step, but we need more observations to know for sure what form of water we’re dealing with,” adds study co-author Håkan Svedhem of the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC).

“Regardless of the outcome, the finding demonstrates the unrivalled abilities of TGO’s instruments in enabling us to ‘see’ below Mars’ surface – and reveals a large, not-too-deep, easily exploitable reservoir of water in this region of Mars.”

The team's study, “The evidence for unusually high hydrogen abundances in the central part of Valles Marineris on Mars”, is published in the journal Icarus.