The first science results from NASA’s Juno mission have been released and Jupiter doesn’t disappoint; along with a gigantic but lumpy magnetic field, this complex, turbulent world has Earth-sized polar cyclones and storm systems that reach deep into the heart of the largest planet in the solar system.

Launched on 5 Aug, 2011, Juno took just under five years to reach the gas giant, before entering its orbit in July of last year. These early findings are from the first data-collection pass, when the spacecraft soared around 4,200 kilometres (2,600 miles) above Jupiter’s cloud tops.

"We are excited to share these early discoveries, which help us better understand what makes Jupiter so fascinating," said Diane Brown, Juno program executive at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “There is so much going on here that we didn't expect that we have had to take a step back and begin to rethink of this as a whole new Jupiter,” added Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio.

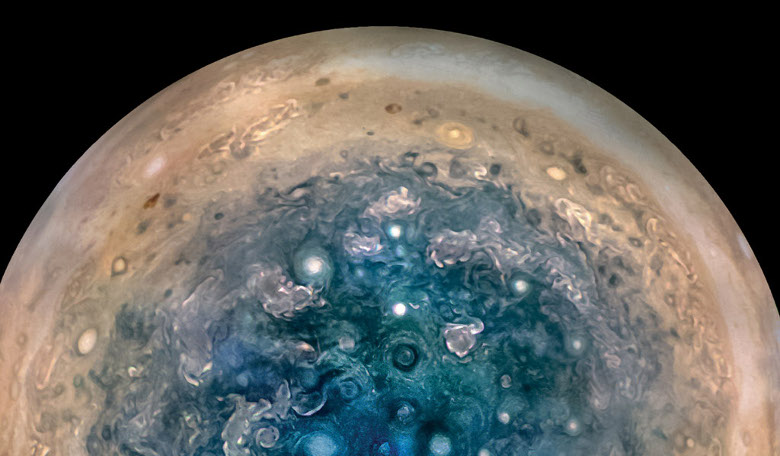

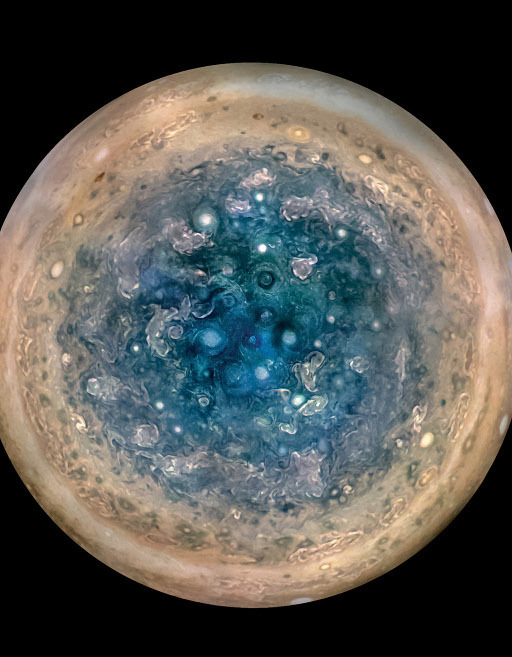

Some puzzling features that has come to light is why both of Jupiter’s poles look different and what is the nature of the Earth-sized swirling storms that are densely clustered around both of its poles that appear to be rubbing together.

"We're questioning whether this is a dynamic system, and are we seeing just one stage, and over the next year, we're going to watch it disappear, or is this a stable configuration and these storms are circulating around one another?" said Bolton.

More revelations have been gleaned from Juno’s Microwave Radiometer (MWR) which allows the instrument to see a few hundred kilometres down into the depths of Jupiter’s atmosphere. The sampled MWR data indicates that Jupiter’s mysterious belts and zones are living up to their name, as the belt near the equator is evident all the way down, while the belts and zones at other latitudes are not so steadfast and seem to transform into other structures. The data is being interpreted that the ammonia which makes up much of Jupiter’s layered cloud system is quite variable but continues to increase as far down as can be seen with the radiometer.

Data on Jupiter’s magnetic field is also getting an overhaul. It was already known that Jupiter had the most intense magnetic field in the solar system, prior to Juno arriving at the gas giant, now measurements taken with Juno's magnetometer investigation (MAG) instrument, indicate that planet’s magnetic field is about 10 times stronger than the strongest magnetic field found on Earth and is also irregular in shape.

"Already we see that the magnetic field looks lumpy: it is stronger in some places and weaker in others. This uneven distribution suggests that the field might be generated by dynamo action closer to the surface, above the layer of metallic hydrogen. Every flyby we execute gets us closer to determining where and how Jupiter's dynamo works,” said Jack Connerney, Juno deputy principal investigator and the lead for the mission's magnetic field investigation at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

At the moment, Juno will be flying around Jupiter in a polar orbit where it remains at a reasonable distance from the planet. However once every 53 days, Juno whizzes down the gas giant from the north to south pole over a two hour period. During the transit, Juno collects around six megabytes of data, which takes around 1.5 days to download.

Juno’s next flyby will be on the 11th July and it will be a widely anticipated venture to study an instantly recognisable feature of this enigmatic planet. "On our next flyby…we will fly directly over one of the most iconic features in the entire solar system – one that every school kid knows – Jupiter's Great Red Spot. If anybody is going to get to the bottom of what is going on below those mammoth swirling crimson cloud tops, it's Juno and her cloud-piercing science instruments,” enthused Bolton.

Jupiter in all of its glory.

Jupiter in all of its glory.