Space has never been a subject left out of April Fool's gags, although some of the jokes resulted in some quite real consequences. Here are just some of the many April Fool's jokes that brought space a little closer to Earth.

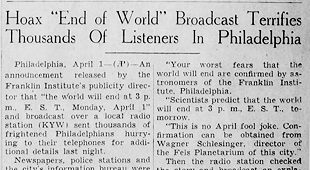

On March 31, 1940, Philadelphia (USA) KYW radio station broadcast the following message: “Your worst fears that the world will end are confirmed by astronomers of Franklin Institute, Philadelphia. Scientists predict that the world will end at 3 P.M. Eastern Standard Time tomorrow. This is no April Fool joke. Confirmation can be obtained from Wagner Schlesinger, director of the Fels Planetarium of this city.” The public's reaction was manifold – hundreds of concerned citizens appealed to the police.

KYW issued a public apology, but noted that as it had received the announcement from William Castellini, press agent at the Franklin Institute, they had read it in good faith, believing it to be true. Castellini in turn claimed that the announcement was a publicity stunt for a lecture at the planetarium, entitled “How Will the World End?” and not meant to be taken seriously. Soon afterwards, he was dismissed from the Franklin Institute.

Two decades later, on April 1, 1958, W.D. Loy of Charlotte, North Carolina (USA) heard a loud bang followed by a series of beeps coming from his front year. Upon investigation he found a silver cylinder shaped like a missile with an antenna at the top on his lawn. Living in the middle of the Cold War and the Space Race, Loy understandably assumed that the object was a fallen Soviet satellite, similar to Sputnik. He sent his family to hide in the basement, called the police, and carried the mysterious object into the center of the road.

As the police arrived and unscrewed the bolts on the outside of the object, they found a beeping electric bicycle horn and a note that read, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. April fool!”.

Officer K.K. Scott posing with the device

Officer K.K. Scott posing with the device

Only a year later, an April Fool's joke inadvertently became the basis for a new scientific theory. Walter Scott Houston, professor of English at Kansas State College and editor of the Great Plains Observer, published an April Fool's article claiming that a Dr. Hayall at the University of the Sierras had reported that the moons of Mars are actually artificial satellites or even space stations, sent up by an unknown and possibly extinct race. Both Dr. Hayall and the University of the Sierras were fictitious, however, soon afterwards, a Soviet scientist, Dr. Iosip Shklovsky, advanced the theory that Phobos, one of the moons of Mars, was hollow and potentially man-made. Although Shklovsky's theory has since been disproven and Phobos' density confirmed (Viking probe images have additionally confirmed that Phobos is a natural object), Shkolvsky's theory did spur further Mars exploration and inspire many a Soviet scientist, proving that no joke is ever just a joke.

Europe is no stranger to April Fool's space jokes. In 1967, a Swiss Radio broadcast announced that U.S. Astronauts had just landed on the moon. The broadcast began with a news flash that interrupted the regularly scheduled show and included staged elements, such as correspondents in cities around the world, interviews with experts, slamming doors and sounds of newscasters running in with breaking bulletins. The announcement generated so much excitement, that telephone exchanges in many places became jammed, as people started calling everyone they knew. Americans vacationing in Switzerland hosted celebrations. The broadcast also claimed that the spaceship would leave the moon at 7pm and listeners were advised to find a high vantage point from which they watch it return home – which in turn resulted to a rush of people who tried to get out of Zurich and get to the top of the nearest mountain. And of course, although this was an elaborate hoax staged by Radio Zurich newscaster Hans Menge, U.S. astronauts really did land on the moon only two years later, in 1969.

On April 1, 1976, in an interview with BBC Radio 2, British astronomer Patrick Moore announced that at 9:47 am, the planet Pluto would pass directly behind Jupiter, creating a combined gravitational force and a stronger tidal pull, which would temporarily counteract the Earth's own gravity and make people weigh less. Moore called this the Jovian-Plutonian Gravitational Effect.

Moore told listeners that they could experience the phenomenon by jumping in the air at the precise moment the alignment occurred. If they did, he promised they would feel a strange floating sensation resembling weightlessness. At 9:47 Moore commanded the jump, and only a minute later calls began flooding the BBC switchboard from people claiming the experiment had worked. While most callers were happy to have experienced the lack of gravity (reports included a party of 11 seated around a table, all of whom began to ascend, including the table itself), at least one caller called with a complaint - apparently he had risen from the ground so quickly that he hit his head on the ceiling.

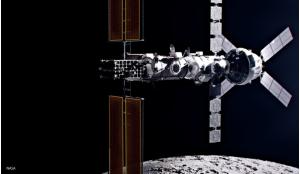

The jokes kept on coming in recent decades. In 2004, they announced that they were accepting applications for positions at Copernicus Center, a new “lunar hosting and research center”. Applicants had to be “capable of surviving with limited access to such modern conveniences as soy low-fat lattes, The Sopranos and a steady supply of oxygen.” The center was to house 35 engineers, two massage therapists and a sushi chef.

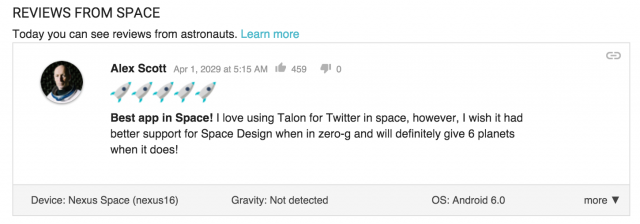

This year, they have launched a new “Space Reviews” section in their developer console, meant to show space reviews sent from outer space with space phones.

No matter the decade, the generation,the country, or the holiday, it seems that here on Earth, space is never too far away!