It has been a busy year already this year for satellite firms wanting to establish their global internet networks in space. Earlier in January, SpaceX launched 60 more satellites of its Starlink mega-constellation into a low-Earth orbit (LEO) and currently sat at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, is a Soyuz-2.1b booster loaded with 34 satellites for OneWeb’s global Internet network due for lift off on Thursday.

This is just the first in a sequence of up to 20 launches from three countries to deploy nearly 650 satellites for OneWeb’s global Internet network; a figure 41, 000 short of the number of satellites SpaceX want to ultimately launch as part of Elon Musk’s Starlink endeavour. And it is a couple of thousand less than the 3,236 satellites planned as part of Jeff Bezos’s Project Kuiper network.

This sheer volume of satellites expected to dominate our skies in the next few years has now prompted a group of astronomers to call for legal action to stop these launches until their impact on the night sky can be assessed.

“Depending on their altitude and surface reflectivity, their contribution to the sky brightness is not negligible for professional ground based observations,” say the group of Italian scientists advocating for action to mitigate the effects of the rising population of small satellites.

Astronomers measure the sky in square degrees and there are over 40 thousand square degrees in the sky. If the satellites were spread out evenly throughout the skies, it can be viewed that for every square degree on the sky, one or more satellites from these new mega-constellations will fill it. “This will inevitably harm professional astronomical images,” the astronomers write.

So far, only one of these super-sized space internet projects have been authorised (to some degree) by the US Federal Communication Commission (FCC) say the Italian team; SpaceX’s Starlink project.

Satellites in this initial constellation are expected to be visible after sunset and before dawn with brightnesses between 3 and 7 magnitudes.

For comparison, Polaris, the North Star has an apparent visual magnitude of +2, the faintest stars visible in an urban neighbourhood have a magnitude of +3 and the faintest stars observable with a naked eye under dark skies have magnitudes of +6.

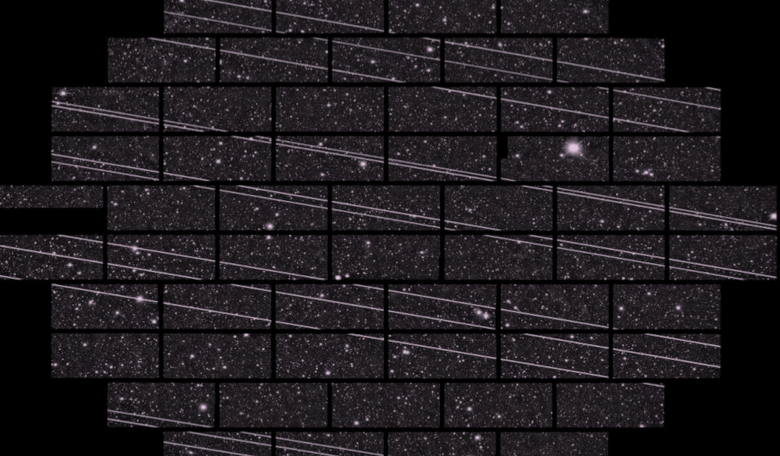

“All satellites will leave several dangerous trails in astronomic images and will be particularly negative for scientific large area images used to search for Near Earth Objects (NEOs),” say the team.

But its not just telescopes that search in visible light that will be affected. The Italian team state that detectors used in radio-astronomy are already swamped by satellite communication signals from space stations as well as from the ground and this situation will be only compounded when these mega-constellations come to fruition.

“Until 2019, the number of such satellites was below 200, but that number is now increasing rapidly, with plans to deploy potentially tens of thousands of them. If no action will be put in place, several problems will soon arise in Astronomical observations,” argue Stefano Gallozzi, Marco Scardia and Michele Maris; the astronomers behind the legal proposal.

And this is not some distant threat: it is already happening warn the astronomers.

To halt this assault on the skies, a case could be brought to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which can be called into question whenever there is a dispute of international jurisdiction or between member states of the United Nations, to argue that the night sky in its natural state is a shared human right, like “the right to breath unpolluted air, drink clean water or sleep in a quiet environment during the night.”

This protection is key to the World Heritage Convention, which holds that; the deterioration or disappearance of any item of the cultural or natural heritage constitutes a harmful impoverishment of the heritage of all the nations of the world.”

“The harm here is damage to our cultural heritage, the night sky, and monetary damages due to the loss of radio and other types of astronomy,” say the Italian group.

This protection is also echoed in the 1994 Universal Declaration of Human Rights for Future Generations, which specifies: “Persons belonging to future generations have the right to an uncontaminated and undamaged Earth, including pure skies; they are entitled to its enjoyment as the ground of human history of culture and social bonds that make each generation and individual a member of one human family.”

The astronomers point out that according to the Outer Space Treaty, only governments can operate in outer space. As such, it is the US government that is responsible for the harm caused by SpaceX’s satellites in orbit.

Accordingly, under this international law, any country that suffers harm by Starlink can sue the United States government in the International Court of Justice. “The pretext for appealing to the United Nations and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the loss of scientific value of the investments made for ground based projects,” write Gallozzi and colleagues

Although the International Astronomical Union (IAU) has also expressed concerns about light and radio pollution produced by artificial satellites, the chances of legal action being successful are slim, but there is an argument that could be made, says Chris Johnson, a space law advisor at the Colorado-based pressure group the Secure World Foundation, in an interview with New Scientist.

“It’s time for the larger space community to think what means more: ground-based astronomy and traditional views of the night sky, or cheaper internet from space,” he says.

Gallozzi and colleagues state it is absolutely necessary to put in place all possible measures to protect the night sky and as such, the team have suggested that Starlink launches (and other projects) be put on hold in the meantime until the situation is properly assessed.

In the meantime, to advance this cause, an international appeal/petition from astronomers has been launched and, at the time of writing, say Gallozzi and colleagues thousands of astronomers involved with astronomical observatories and facilities, have subscribed to the appeal.