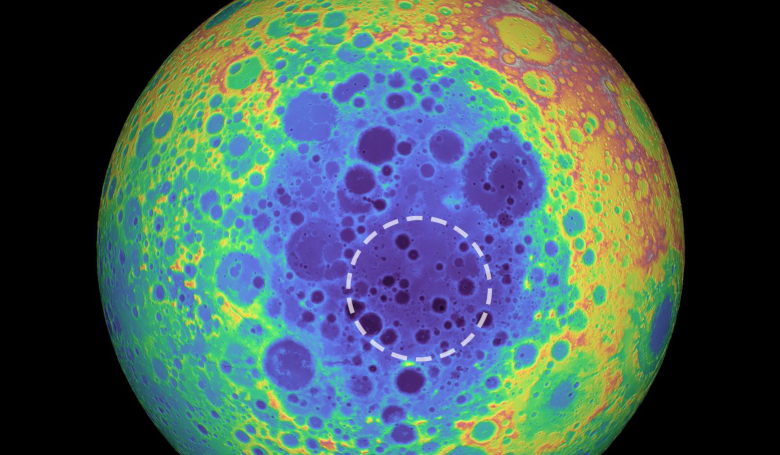

At roughly 2,500 kilometres (1,600 miles) in diameter and 13 kilometres (8.1 miles) deep, the South Pole–Aitken basin on the far side of the Moon is one of the largest known impact craters in the Solar System, and now scientists have found a mysterious large, possibly metallic mass of material five times larger than the Big Island of Hawaii hiding under it.

The anomalous mass, which instantly conjures up conspiracy theories involving hidden alien bases, was discovered by researchers measuring subtle changes in the strength of gravity around the Moon. The data used had been collected by NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission; twin spacecraft dubbed Ebb and Flow that launched in 2011 and orbited the Moon for nearly a year. Flying in tandem, the duo mapped differences in density of the Moon's crust and mantle to generate the highest resolution gravity field map of any celestial body.

"When we combined that with lunar topography data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, we discovered the unexpectedly large amount of mass hundreds of miles underneath the South Pole-Aitken basin," said Peter B. James, assistant professor of planetary geophysics in Baylor's College of Arts & Sciences and lead author of the recent research published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The deep structure, which is dragging down the floor of the basin by more than half a mile, is most likely a remnant of what created the crater in the first place; the iron-nickel core of an asteroid that dispersed into the Moon’s upper mantle (the layer between the crust and core) during an impact.

"We did the math and showed that a sufficiently dispersed core of the asteroid that made the impact could remain suspended in the Moon's mantle until the present day, rather than sinking to the Moon's core," James said, after him and his team ran computer simulations to understand the effects of large asteroid impacts.

There is a chance that the mysterious mass is something else altogether and the team have suggested another possible explanation; a concentration of dense oxides that formed in the final stages of cooling when the moon was covered in magma oceans billions of years ago. However, as reasonable as it might sound, even the researchers cannot fully explain how such a layer formed here and nowhere else.

The South Pole–Aitken basin is however "one of the best natural laboratories for studying catastrophic impact events” said James, due to its high level of preservation. Collisions between planets and smaller rocky or icy objects were rife throughout the Solar System in its early history, even on Earth, but not many traces of larger impacts remain on our planet due to our ever-shifting terrain. If any feature can reveal more information on cataclysmic events such as these, then this is the place to look.

And, with this relatively unknown region on our nearest celestial neighbour becoming the target of interest for many up and coming missions to the Moon, it is perhaps possible that the precise nature of this mysterious mass could be uncovered in the next decade, if not before.