Needing less power than a pair of 100-watt light bulbs to perform its mission, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft makes history, again, by getting within 3,500 kilometres (2,200 miles) of the icy world known as Ultima Thule; a 30 kilometre remnant from the birth of our solar system.

At over 6.5 billion kilometres (4 billion miles) away from Earth, the rendezvous makes it the most distant ever exploration of an object in our Solar System; a feat that comes with a small downside for an eager mission crew waiting for news back on Earth. New Horizons can't talk to NASA and point to take observations at the same time, so controllers had to wait an agonising six hours after the post-flyby signal was sent by New Horizons to confirm it had reached its objective.

But the wait has been more than worth it, and after picking up the radio message sent by the spacecraft to one of NASA’s big antennas, in Madrid, Spain, mission crew at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland were thrilled to report they have a “healthy spacecraft” on the border of the Kuiper Belt.

"New Horizons performed as planned, conducting the farthest exploration of any world in history — 4 billion miles from the Sun," said Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. "The data we have look fantastic and we're already learning about Ultima from up close.

The probe has already collected gigabytes of photos and other observations during the fly-by and a few are expected to be released to the public shortly.

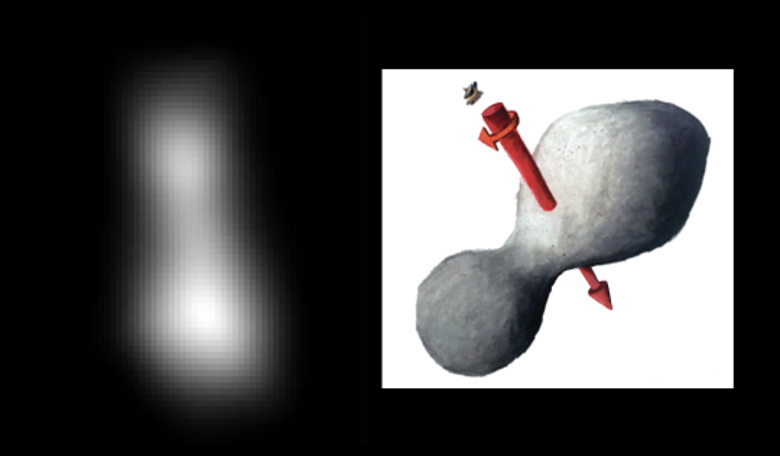

Designated 2014 MU69, but nicknamed "Ultima Thule,” which means "beyond the known world,” this irregular-shaped distant object has been affectionately described as a spinning chicken drumstick, or a bowling pin. Either way not a lot is known about Ultima, except that it is reddish in colour, and that it receives only about 0.05 percent of the light from the Sun that Earth does.

However frequent fly-bys planned for New Horizon will soon change all of that. Although the first of the very highest resolution pictures are expected to be received by ground crew in February, work to decipher the rudimentary characteristics of Ultima will start very soon.

"The [lower resolution] images that come down this week will already reveal the basic geology and structure of Ultima for us, and we're going to start writing our first scientific paper next week," said Principal Investigator Alan Stern.