In an usual geological twist, scientists may have discovered the oldest Earth rock ever — not on our planet though, but on the Moon.

The surprising find has been uncovered by an international team of scientists who had been studying a lunar sample returned by the Apollo 14 astronauts from their mission 48 years ago.

The 2 gram fragment of rock, which is a possible relic from the Hadean epoch on Earth, contains quartz, feldspar, and zircon - minerals that are all commonly found on Earth but are highly unusual on the Moon, especially the quartz.

"By determining the age of zircon found in the sample, we were able to pinpoint the age of the host rock at about four billion years old, making it similar to the oldest rocks on Earth,” said research author Professor Alexander Nemchin, from Curtin's School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Perth. "In addition, the chemistry of the zircon in this sample is very different from that of every other zircon grain ever analysed in lunar samples, and remarkably similar to that of zircons found on Earth,” added Nemchin.

The chemistry, the professor alludes to, is characteristic of zircon that has crystallised in a terrestrial-like oxidised system, at terrestrial temperatures, rather than in the low water and higher temperature conditions associated of the Moon.

So just how did the ancient Earth rock end up on our lunar neighbour eons ago? After developing techniques for locating impactor fragments in the lunar regolith, the international team, who also includes research Scientist Jeremy Bellucci, concluded that the rock was flung from our planet when a large asteroid or comet impacted the Earth, sending this and other material flying through our primitive atmosphere, which subsequently collided with the surface of the Moon.

At the time, about 4 billion years ago, the Moon was three times closer to Earth than it is now, so the probability of a collision with our lunar neighbour was higher. And in the years since, the rock has been subsequently mixed with other lunar surface materials into one sample.

“It is an extraordinary find that helps paint a better picture of early Earth and the bombardment that modified our planet during the dawn of life,” says Dr. David Kring, a Universities Space Research Association (USRA) scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI).

There is the possibility however that the sample actually did form on the Moon and is not of terrestrial origin, although this would require the sample to have formed at tremendous depths in the lunar mantle, where very different rock compositions are anticipated - conditions that other lunar samples have never before inferred.

Consequently, the simplest explanation is that the rock is a misplaced home grown sample that found its way to the Moon a long time ago - an interpretation that Kring suspects others scientists will find controversial. Nonetheless, the surface of the Moon is big and the sample collection returned so far is small, therefore there is a chance that more could be found with further studies.

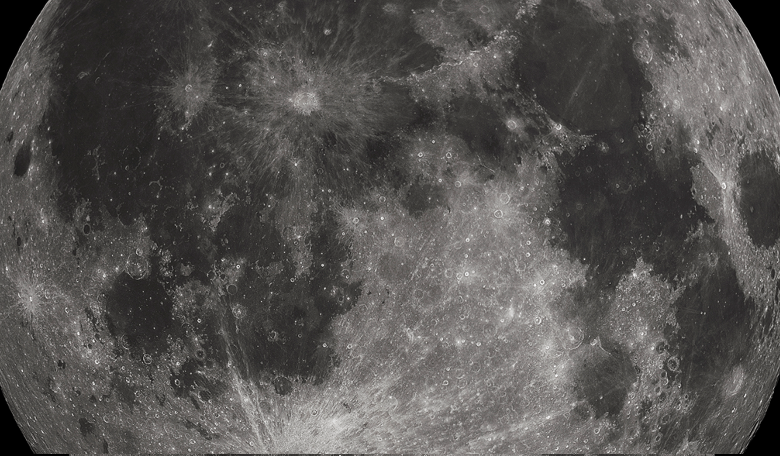

Rock fragment from the Moon. Image: NASA