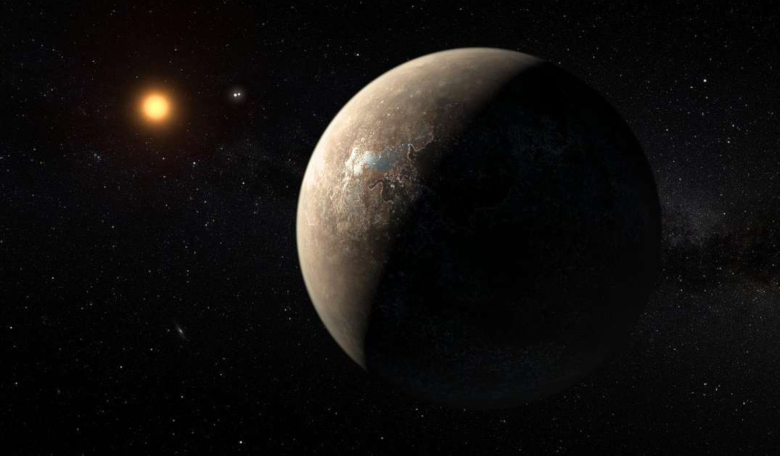

In 2016, astronomers announced the discovery of a rocky planet not much bigger than Earth orbiting every 11 days around the nearest star to us; Proxima Centauri. Now a different team of researchers have found another, except this one is approximately six times more massive.

Finding exoplanets like our own world is exciting enough, but finding one in our cosmic backyard is exhilarating on a whole different level and when that happens, people become intoxicated with the idea of flying there to look at it close up. Finding two such planets, well, what could beat that? Finding a third maybe?

Proxima Centauri is approximately 4.2 light years away from us and while it is smaller and cooler than our Sun, any planets orbiting close within its ‘habitable zone’ could have water in a liquid state, if any were present on its surface. This is the scenario that was envisaged for Proxima b, when news of its discovery was circulated nearly three years ago and studies began in earnest to try and decipher its climate and environment.

The new planet however, which although has yet to be given a name could end up being called Proxima c (please note, this is not an official title), is not so temperate like its smaller neighbour. Found by a team who include Fabio Del Sordo with the University of Crete and Mario Damasso with the Observatory of Turin, the researchers state that Proxima c takes five Earth years to make one orbit around its star. As such its long distance – around 1.5 AU from its host star – would likely mean very cold temperatures on this super-Earth sized exoplanet, maybe even as cold as -234 degrees Celsius, because of the relative coolness of Proxima Centauri.

Hopes of finding a true Earth-like water-world would then surely rest with Proxima b; a possible twin Earth but just a bit smaller. Perhaps not. When news spread that an exoplanet had been found around our nearest star, telescopes around the world were taken up by researchers hoping to spot the same tell-tale signs that alerted astronomers to the presence of Proxima Centauri in the first place. But these signs have proved too elusive for some.

“We performed a general planet search from 1 – 30 days and found no evidence of transits that would be due to an exoplanet of Proxima b's radius and orbital period,” said Dax Feliz, an astronomy graduate student and research assistant at Vanderbilt University, in Tennessee, US.

That doesn't necessarily mean Proxima b doesn't exist, added Feliz as he spoke to ROOM about his recent search for the closest exoplanet to us, just that there are many hurdles to overcome to establish a genuine signal.

“One of the challenges of observing transiting exoplanets around M-Dwarf stars are the very low geometric transit probabilities for exoplanets,” Feliz said. Transits can only be detected if the planetary orbit is near the line-of-sight (LOS) between the observer and the star and if it fits within a certain range of angles, that are calculated from the star’s diameter and the planet's orbital radius.

“In Proxima b's case, the transit probability is about 1.5 percent and this is supported by our lack of detections of transit events,” he added.

But, said Feliz, in their search for Proxima b, he and other team members only looked for transits that were perfectly in the line of sight and across the face of the star. “There are several publications about Proxima b's orbital parameters such as its orbital inclination [the tilt of an object's orbit] and eccentricity [how circular its orbit is] that we did not consider since we were looking for best case transit scenarios,” said Feliz.

These additional orbital parameters are something that will be looked at in a further study in the continued search for Proxima b, Feliz concluded. Nonetheless, Feliz and his colleagues are not alone in their observations. Other researchers have also found a lack of viable signals to conclusively acknowledge what had become, a possible Earthly home away from home.

Why is this the case? Scientists searching for exoplanets around Proxima Centauri are up against a force of nature that will be hard to overcome - the star’s variability in brightness. Proxima Centauri is a flare star, meaning that our nearest stellar neighbour experiences unpredictable dramatic increases in its radiation output due to irregular outbursts of energy. This makes searching for an exoplanet via the transit method very difficult to say the least.

Could the signals that Del Sordo and Damasso saw in their search for Proxima c be contamination due to a flaring star or were they solely those of a transiting exoplanet?

It should be noted that studies by both Del Sordo and Damasso and Anglada-Escude who spotted Proxima b back in 2016, used the radial velocity or “doppler shift" method to detect Proxima c and b respectively. Radial velocity is an indirect method which relies on observing a star’s spectra for signs of a “wobble.” This is an indication that a planet is exerting a gravitational influence on its host star and therefore causing the star to 'wobble' or move towards and away from Earth

Feliz on the other hand used the transit method. This technique detects distant planets by measuring the minute dimming of a star as an orbiting planet passes between it and the Earth. Both have their strengths and weaknesses and up until around 2011 the radial method was the primary technique for locating extrasolar planets. Since then though, the transit method has overtaken it to become the most productive process used by planet hunters to find distant worlds.

As for Proxima c, Del Sordo and Damasso state that they are confident that they have found a new exoplanet, but on the other hand, they are also remaining cautious. Details about their observations have been submitted for publication by the team but have not yet been peer reviewed.