Proxima Centauri, the host star of the recently discovered exoplanet Proxima b, and our closest stellar neighbour has more surprises in store as scientists say that despite being a cool, red dwarf, the star has a regular cycle of sunspots.

At first glance, Proxima Centauri seems nothing like our Sun as it is only one-tenth as massive and one-thousandth as luminous. Our Sun also experiences an 11-year sun spot activity cycle that sees the Sun’s surface nearly spot-free during a solar minimum, whilst during a solar maximum typically more than 100 sunspots cover less than one percent of the Sun's surface on average.

Now, a new study by scientists at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) have discovered that Proxima Centauri also undergoes a similar cycle except it only lasts seven years from peak to peak and its cycle is much more dramatic. Not only are some of those spots much bigger relative to the star's size than the spots on our Sun but at least a full one-fifth of the star's surface is covered in spots at once.

"If intelligent aliens were living on Proxima b, they would have a very dramatic view," says lead author of the research, Brad Wargelin of the CfA.

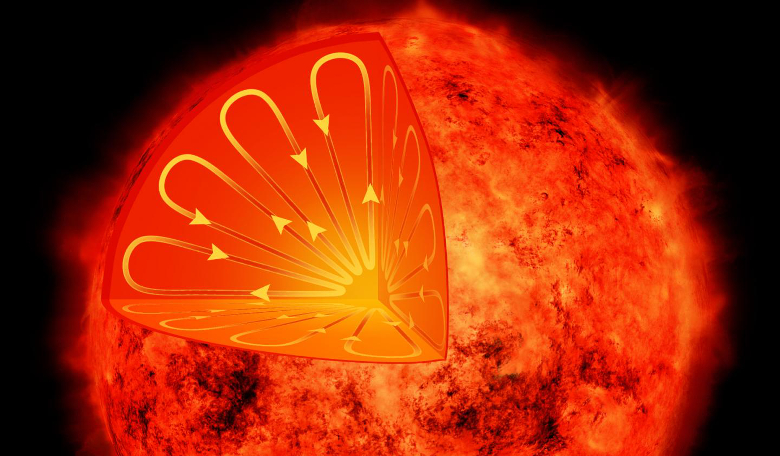

Sun spots are regions of strong magnetic fields and scientists believe that the different rotational speeds of the Sun’s interior, which rotates more like a solid body, compared with its exterior (where convection occurs) causes magnetic field lines to break through the visible surface (photosphere) of the Sun. As the lines break through the surface, one sunspot of a certain polarity is formed and where the lines plunge back down again, it creates another sunspot with an opposing polarity.

Sunspots are darker than the surrounding areas and have a lower temperature. One theory as to why the temperature can differ as much as 2000 kelvin (1727 degrees celsius) is that the strong magnetic fields in these spots inhibit convection below the surface (convection is the transfer of heat from a hot location to a cold one.)

For bodies like Proxima Centauri however, the interior of a small red dwarf star should be convective all the way into the star's core, so accordingly it shouldn't experience a regular cycle of activity. "The existence of a cycle in Proxima Centauri shows that we don't understand how stars' magnetic fields are generated as well as we thought we did," says Smithsonian co-author Jeremy Drake.

How these relatively fierce sunspots on Proxima Centauri affects the potential habitability of Proxima b is unknown. Some theories have already been proposed including that a stellar wind or flares driven by magnetic fields, could strip away any atmosphere of the planet leaving its surface barren. However proving this is a long way off yet.

"Direct observations of Proxima b won't happen for a long time. Until then, our best bet is to study the star and then plug that information into theories about star-planet interactions," says co-author Steve Saar.