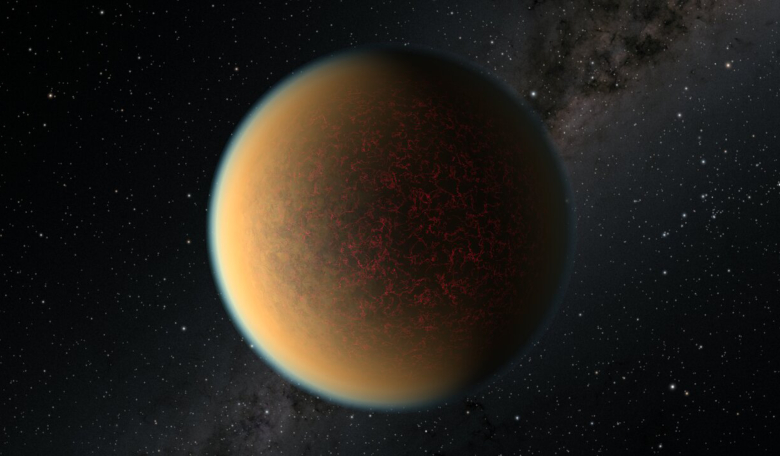

Scientists studying GJ 1132 b, an exoplanet around a distant star, have found that this once gaseous planet which looked like Neptune is now a hot, rocky world with a poisonous atmosphere made from volcanic activity; a finding that shows planets can be transformed through drastic physical changes.

GJ 1132 b is a lot like Earth in many respects; it is of a similar density, similar size, and, at about 4.5 billion years old, it is also similar in age. It might even have a similar atmospheric pressure at the surface according, say an international team of astronomers who have recently published a study on this exoworld

But despite these common attributes, that is where the similarities stop, as GJ 1132 b is thought to be the irradiated core of a once gaseous giant. Scientists think that in its former life, GJ 1132 b was cocooned in a thick primordial atmosphere made up of hydrogen and helium.

However, in a relatively short period of time, it was reduced to a bare core about the size of Earth after its atmosphere was stripped away by the intense radiation emanating from the hot, young star it orbits once every day and a half.

This extremely close proximity to its host star keeps GJ 1132 b tidally locked, meaning it shows the same face to its star at all times, just as our moon keeps one side permanently facing Earth.

Although the case for GJ 1132 b might seem cut and dry, interest in the exoplanets atmosphere was revived when a different team of researchers using ground-based instruments suggested that GJ 1132 b might actually have a water (H2O) rich atmosphere.

Detecting molecular species on other celestial objects using telescopes on Earth comes with many challenges, as water in our atmosphere can interfere with observations.

To help clarify what the situation on GJ 1132 b was, a team headed by Mark Swain of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, decided to point the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope at the exoplanet instead.

To the team’s surprise, observations with Hubble picked up spectral signs of hydrogen cyanide (HCN), methane, and an aerosol haze – not the water-rich one previously indicated.

Where did this “secondary atmosphere” come from? Volcanoes, say the team.

With the aid of computer modeling Swain’s team theorise that hydrogen from the original atmosphere was absorbed into the planet’s molten magma mantle and is now being slowly released by volcanic outgassing to form a new atmosphere.

This hydrocarbon atmosphere, which is similar to smog on Earth, is continually being replenished from the reservoir of hydrogen in the mantle’s magma as it leaks away into space say the team.

“This second atmosphere comes from the surface and interior of the planet, and so it is a window onto the geology of another world,” explained team member Paul Rimmer of the University of Cambridge, UK. “A lot more work needs to be done to properly look through it, but the discovery of this window is of great importance.”

Because of its close proximity to its host star, Swain and colleagues suggest that GJ 1132 b acts a lot like Jupiter’s moon Io.

Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system and its extreme geologic nature is down to tidal heating from friction generated within Io's interior as it is pulled between Jupiter and the other Galilean moons.

Caught between its host star and at least one other planet in the system, GJ 1132 b is also experiencing a constant tidal tug-of-war resulting in a mantle that is kept liquid for a long time. “This system is special because it has the opportunity for quite a lot of tidal heating,” Swain says.

Determining just how special this world might will have to wait until the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is up and running – a mission that is expected to finally launch later this year after continual delays have setback its completion date.

Then, says Swain, there is a possibility that astronomers will see not the spectrum of the atmosphere, “but rather the spectrum of the surface”. And if there are magma pools or volcanism going on, he adds, those areas will be hotter.

“That will generate more emission, and so they’ll potentially be looking at the actual geological activity — which is exciting!” Swain says.

Whats more, it will also allow exoplanet scientists a way to figure out something about a planet's geology from its atmosphere, added Rimmer. “It is also important for understanding where the rocky planets in our own Solar System — Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, fit into the bigger picture of comparative planetology, in terms of the availability of hydrogen versus oxygen in the atmosphere.”