Scientists at the US National Science Foundation’s National Solar Observatory are now able to predict when sunspots will emerge on the solar surface, by “listening” to changing sound waves coming from the Sun’s interior; a finding that can help mitigate the effects of powerful solar storms that have the potential to disrupt satellites in orbit and produce electrical surges around the planet.

Known as helioseismology, this specialist technique has recently been used by researchers at the NSF, who on 18 November forewarned that a new batch of sunspots were due to emerge this week - just in time for the US holiday of Thanksgiving.

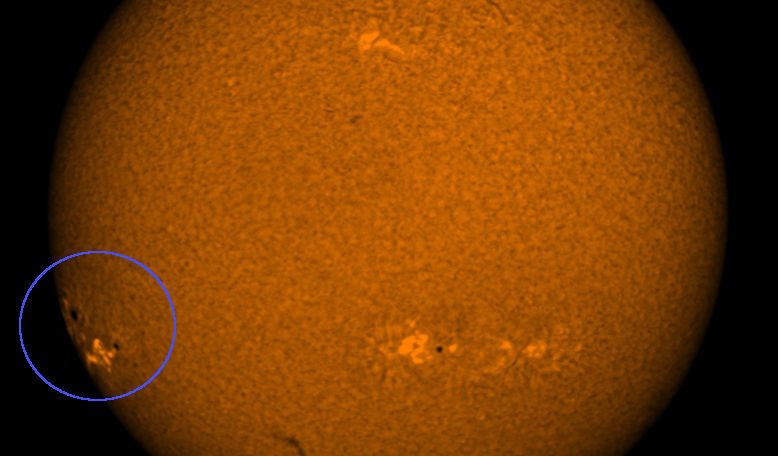

As predicted, a fast-evolving sunspot that has been dubbed “the strongest far-side signal" yet to be encountered during this solar cycle, has now appeared near the eastern solar limb, and can be seen from Earth.

“We measured a change in acoustic signals on the far-side of the Sun”, explains Dr. Alexei Pevtsov, Associate Director for NSO’s Integrated Synoptic Program, the program responsible for the prediction. “We can use this technique to identify what is happening on the side of the Sun that faces away from Earth days before we can catch a glimpse from here.”

Helioseismology is similar in principle to the way sound waves travelling through Earth’s interior are measured. Referred to simply as seismology, this method reveals features beneath the Earth’s surface that otherwise could not be seen.

Like Earth, millions of sound frequencies also bounce freely throughout the Sun’s interior, but when regions of strong magnetic fields appear, these perturb the sound waves causing a change in the wave signal measurements recorded on our planet.

This change then allows scientists to determine if sunspots may be present. As such, helioseismology helps researchers ‘see’ structures on the solar surface that have yet to be visible on Earth.

The technique is very advantageous as it can give up to five days lead time on the presence of active sun spots – a warning that is extremely valuable to our technology-heavy society, says Pevtsov.

Active sunspots are often the starting point for solar storms, especially if the sunspot is large and complicated. Solar storms involve the sudden releases of stored magnetic energy and the more tangled the magnetic field, the more likely it will result in large solar flares and coronal mass ejections that can end up on a collision course with Earth.

When the charged solar particles hit Earth's magnetic field, it can dump the ions into our upper atmosphere and cause Auroras.

The same charged particles can also impact communications, GPS and electrical grid systems by producing electrical surges that lead to black outs.

Presently, the US National Solar Observatory provides “eyes on the Sun” all day every day through the GONG network which is funded by NSF and NOAA and consists of six monitoring stations positioned across the globe.

“The ability of GONG to identify and track active regions emergent on the far side of the Sun has important implications for future space weather predictive capabilities,” said Dr. Carrie Black, Program Director at NSF. “GONG continues to be a valuable tool for both fundamental science research and operations.”

But, says Dr. Valentin Martinez Pillet, Director of the National Solar Observatory, although the GONG network is providing an essential service to United States space weather preparedness, it is close to three decades old and is in need of an upgrade. “The original system was not created with space weather in mind, so we are exploring options for the Next Generation GONG network, with modern instrumentation specially attuned with space weather as a priority,” Pillet advises.

In the meantime, the NSF team will be carefully watching the evolution of the new sunspot group, which was first identified in far-side images on 14 November, 2020.

“It was inconspicuous at first but grew quickly, breaking detection thresholds just one day later,” says Dr. Kiran Jain, the scientist who is leading the far side prediction at NSO.

“Since we are in the very early phase of the new solar cycle, the signal from this large spot stands out clearly.”