It's official – on June 23rd, the UK has voted to leave the European Union. The leaving process is expected to be gradual and take about two years. In light of this historic vote, it is yet unclear what the consequences will be for the British role in the European space program.

The British

scientific community has largely opposed Brexit, with a March poll in

Natureshowing that an overwhelming 83% were against leaving

the EU. According to an open letter published in

The Times and

signed by 150 Cambridge academics, including Stephen Hawking, leaving

the EU would be a “disaster for U.K. science and universities.”

One

of the main concerns in research and development is funding. The EU

had budgeted approximately €120 billion to support research and

innovation projects from 2014 to 2020, with much of that funding

intended to benefit Britain. According to the UK Office of National

Statistics, between 2007 and 2013, the UK had contributed an

estimated €5.4 billion to EU research and development, while

receiving €8.8 billion in direct EU funding for research,

development, and innovation, according to a 2016 Royal Society

report.

Many issues remain unclear in other aspects of the space

program, including that of Britain's relationship with the European

Space Agency. Over three quarters of the funds Britain spends on

space programs is sent to ESA, which is not a European Union

organization. As noted by ESA Director-General Johann-Dietrich

Woerner, there is no requirement for ESA members to be part of the EU

(both Switzerland and Norway are ESA, but not EU members). Therefore,

in theory, Brexit should not have a significant impact on British ESA

membership.

At the same time, some ESA programs are joint initiatives with the EU – the most well-known one being the €4.3 billion Copernicus program. The Copernicus project provides data on issues ranging from climate change to oil drilling opportunities. Once in space, the satellites are owned by the EU.

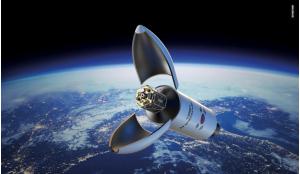

Galileo positioning, navigation and

timing network also presents a problem after Brexit. While Galileo is

owned by the European Commission, its prime contractor for payload

electronics is the British Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. (SSTL).

Twenty-two Galileo satellites were made by German OHB SE before

Brexit, but it is now unclear what will happen with the future

Galileo satellites. The deadline set by ESA for industry bids on the

next Galileo series is July 19

th. OHB Chief Executive

Marco R. Fuchs has said his company is bidding the same OHB-SSTL team

that won the previous order, although he concedes the consequences of

Brexit have been a concern. Norway is able to participate in the

Galileo program after having signed a security treaty with the EU –

but as Britain's role in the program has so far been central, it is

yet unclear whether such a treaty would be sufficient to retain its

place in the Galileo initiative.

The Norwegian experience also

highlights some of the other issues that may soon be faced by

Britain. So far, Britain has actively participated in the Public

Regulated Service, which provides protected, encrypted signals

reserved for military and government customers. Norway does not have

access to this service, even with the security treaty in place.

From the economic side, the British space industry has been growing much faster than the British economy in recent years, with various companies both in the EU and the US and Canada creating British divisions to get access to ESA and European Union space project funding. The British share of global space commerce had been expected to reach 10% by 2023 (currently at 6.5%), but it is now unclear how Brexit will affect both the British market share and investments from other countries.

Some of the other questions that are being raised after Brexit concern satellite fleet operators. French Eutelsat houses its Quantum flexible-payload satellite program in Britain – the program is funded by British money from ESA. The company's Broadband for Africa project (partnered with Facebook), is also located in Britain, as is Eutelsat’s Global Government division.

Overall, the June 23rd vote raises multiple questions concerning various aspects of the British role in European space programs and so far the answers are lacking. As Britain prepares to leave the European Union, many issues concerning its presence in European space programs will need to be evaluated and resolved.