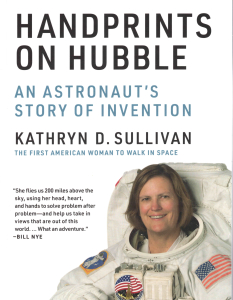

Astronaut Kathryn Sullivan begins her story with her interview for NASA’s astronaut corps, a ninety minute grilling from “fourteen experienced space professionals” that put the 26-year-old on the road to a Hubble Space Telescope (HST) repair mission. That’s not where most job interviews lead, but we are talking about a ‘special breed’ here; in the 60-plus years of the Space Age only about 600 people have reached orbit.

Before the interview that would change her life, Sullivan was expecting a career in oceanography. When her mother asked her to explain the significance of the interview, Sullivan told her: “It means that when I finish my [PhD] degree I’m either going two hundred miles up or six thousand feet down”. After a long, concerned silence, her mother asked: “Isn’t there anything exciting on the surface?”. As with this example, Sullivan writes about her subject in a way that allows us to associate with it, drawing parallels with our own experiences and emotions.

This well-written book takes the reader through Sullivan’s training as a Shuttle astronaut, the history of the Large Space Telescope (which became the HST) and the preparations for its repair in orbit, after its main mirror was found to have been incorrectly manufactured. The book is illustrated with colour photos and includes chapter notes, a bibliography and an index.

The fascinating technicalities are interspersed with snippets of humanity, such as arguments about NASA management, being seated next to President Ronald Reagan at a White House dinner, and the disappointment of a scrubbed launch. Her choice of “best one-liner” was the result of a Main Engine Cut-Off six seconds before lift-off, when a colleague quipped: “Gee, I thought we’d be higher than this at MECO”.

The book’s title is derived from the scuff marks on the Hubble’s outer skin left by the gloved hands of the astronauts who conducted the in-orbit maintenance programme. Although Sullivan was the first American woman to conduct an EVA (in 1984), she didn’t get to lay hands on the telescope herself: she was left waiting in the Shuttle airlock in case astronauts were needed to help with the Hubble deployment in 1990. The resultant sense of frustration, or loss, is palpable in the book’s final paragraph: “These visible handprints are like the tip of an iceberg…To me they symbolise the countless earthbound hands [that worked on the telescope’s maintainability]. “Each of these unsung people can rightly claim to also have left their handprints on Hubble”.