Russia and the United States are adversaries once again. The eruption of the Ukraine crisis in 2014 marked a historic turning point, putting an end to the fitful efforts to build a partnership since the end of the Cold War a generation ago. Relations had been deteriorating since the autumn of 2011, when Vladimir Putin announced his intention to reclaim the Russian presidency. Also the accusations that the US lay behind the massive anti-Kremlin demonstrations in Moscow in 2011 and 2012 played a role; sharp differences over developments in the Middle East, especially Syria; and Russia’s offer of asylum to US National Security Agency leaker Edward Snowden in 2013.

But the Ukraine crisis precipitated a qualitative change. Official channels of communication were circumscribed, if not completely severed. The operations of the Bilateral Presidential Commission, a mechanism for managing relations across a broad range of political, security and socio-economic issues, were suspended, as were most bilateral programmes and projects. Non-official contacts suffered, as businessmen, scientists, academicians and others hesitated to make commitments, given the uncertainties. Americans, who had long demonised Putin, have now begun to demonise Russia, while anti-Americanism has flourished in Russia, with Kremlin support.

The mutual estrangement was on vivid display at the United Nations General Assembly annual debate in late September 2014. President Obama placed Russia, because of its “aggression” against Ukraine, among the top three foreign policy challenges the United States faces today, along with the Ebola pandemic threat and ISIS. A few days later, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov shot back, in formal remarks and interviews, accusing the US and its western partners of running roughshod over international law and democratic principles in an effort to achieve global hegemony. Meanwhile, no end to the Ukraine crisis is in sight.

Many western and Russian commentators have declared the outbreak of ‘Cold War II’. That is far from the mark. The original Cold War was a global existential struggle in a bipolar world dominated by two superpowers – the United States and the Soviet Union – divided by a vast ideological chasm, by diametrically opposed views of man, productive activity and the relationship between the state and society. Both sides viewed global events through the prism of their rivalry and fashioned their foreign policies accordingly. The two superpowers defined the international system and bore ultimate responsibility for questions of war and peace.

Today’s world is radically different. Russia and the United States compete in an increasingly multipolar setting, argue over the interpretation of the values of a shared European civilisation, and are compelled to work with an array of states on global security. The US might remain the pre-eminent power. But if the US has a strategic competitor today, it is a rising China.

Ironically, the very fact that a repeat of the Cold War is impossible accelerates the deterioration in relations. It is precisely the belief that the two countries do not together dominate the global stage that makes the quality of their relationship less important to both. If Washington, for example, no longer believes Russia is critical to the advance of American interests, or to global stability and security more broadly, it does not need to give much thought to the consequences of its policies for the state of relations. The sanctions that the United States – along with the rest of the west – has levied against Russia because of its actions in Ukraine underscore that point. Sanctions have done little to deter Russia in Ukraine, but the US continues to use them to punish Russia because that sates its moral outrage at Russia’s “aggression” without jeopardising, in Washington’s view, any significant national interest.

The tense estrangement between Russian President Vladimir Putin and US President Barack Obama was evident at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Beijing, November 2014

By the same token, Moscow’s conviction that it has alternatives to the United States – most notably China – makes it less eager to restore relations. Tellingly, as the west levied sanctions last spring, Putin travelled to China to celebrate a burgeoning strategic partnership. The showpiece was a $400 billion deal to bring Russian gas to Chinese markets. Similarly, Putin has made a special effort in recent months to highlight closer relations with other emerging markets. He has made a point of working with partners in the BRICS (Brazil, India, China and South Africa) to challenge western domination of the global economy.

Access to space

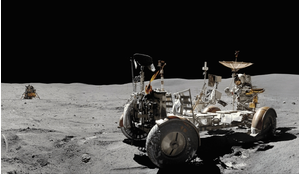

Perhaps the best example of this mutual unwillingness to staunch the deterioration in relations is the rapidity with which the US moved to pare back cooperation in space. Both Russians and Americans of a certain generation will have vivid memories of the Apollo–Soyuz mission in 1975 as a striking symbol of the possibilities of cooperation between global rivals and the hopes of a better world. Although that was the last joint US–Soviet manned mission, cooperation in space continued, with ups and downs, through the end of the Cold War.

It only deepened in the immediate post-Soviet years, as Russia abandoned its separate effort to maintain an orbiting space station, Mir, and joined the US and other nations in support of the International Space Station (ISS). American officials became so comfortable working with Russia in space that as the US wound down its Space Shuttle programme (finally ended in 2011) and left itself at least temporarily without independent access to the ISS, it was willing to rely on Russia for that. At the same time, the US became dependent on Russia providing powerful engines, the RD180s, for the Atlas V rockets to launch its most important military satellites into orbit, and many US firms used Russian launch services for their commercial satellites.

But after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, NASA suspended all contact with Russian entities. While it continues to cooperate with Roscosmos to maintain a safe and secure environment on the ISS, NASA has stressed it will focus on ways to end reliance on Russia for access to space. In response, the Russians have declared that they have no intention to cooperate in bringing American astronauts to the ISS after 2020 and have threatened to ban the export of the RD180s to the United States for military launches.

The deterioration in relations will close off for the immediate future potentially promising cooperation in other high-tech fields with applications for space exploration

May 2014, fresh graffiti depicting the Kremlin, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and the Russian flag, on the wall of a residential building in the Crimean port of Sevastopol

May 2014, fresh graffiti depicting the Kremlin, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and the Russian flag, on the wall of a residential building in the Crimean port of Sevastopol

Meanwhile, the US decision to ban exports to Russia of defence and dual-use technologies, including satellites, has disrupted many companies’ launch plans.

While most of the cooperation in the Cold War was focused on arms control, in the post-Soviet period it expanded rapidly to include securing nuclear materials in Russia and elsewhere in the former Soviet space, developing more proliferation-resistant nuclear reactors, and developing ways to mitigate the consequences of nuclear accidents. In 2011, the United States and Russia concluded a so-called 123 Agreement that allowed for closer cooperation on civil nuclear matters, and just last year they signed a protocol to continue most of the activities that had taken place within the framework of the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR or Nunn–Lugar) agreement, which was about to lapse.

Since the start of the Ukraine crisis, however, no new bilateral programmes have been initiated under this protocol, and US sanctions will put an end to civil nuclear cooperation. At the same time, the Ukraine crisis has killed any lingering hopes the Obama administration might have had for another arms control agreement with Russia. Meanwhile, the growing anti-Russian mood in Washington at least in part led the administration to make a forceful public accusation that Russia was in violation of its commitments under the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty) signed in 1987. (Earlier, such concerns were handled more quietly in formal bilateral arms-control channels.)

Re-thinking the relationship

Finally, the deterioration in relations will close off for at least the immediate future potentially promising cooperation in other high-tech fields with applications for space exploration, which would take advantage of each country’s strong scientific tradition. A cyber working group under the Bilateral Presidential Commission, set up just last year, never had a chance to take a first serious step. There are other possibilities in such areas as 3D printing, nanotechnology and biogenetics that now might not be considered.

NASA and Roscosmos still cooperate to ensure a safe environment on the International Space Station. The crew of Expedition 41/42, from left, Flight Engineer Elena Serova, Commander Alexander Samokutyaev (both Roscosmos) and Flight Engineer Barry Wilmore (NASA) joke during a dress rehearsal, ahead of their launch in September 2014

NASA and Roscosmos still cooperate to ensure a safe environment on the International Space Station. The crew of Expedition 41/42, from left, Flight Engineer Elena Serova, Commander Alexander Samokutyaev (both Roscosmos) and Flight Engineer Barry Wilmore (NASA) joke during a dress rehearsal, ahead of their launch in September 2014

When this situation will change is difficult to foresee. We have reached a historic moment of reassessment. For the past 25 years, the west’s ambition was to integrate Russia into the west, largely on western terms, as a full-blooded democratic and free-market country.

After rising to power 15 years ago, Putin seemed to have been striving for that goal. But over the years, he grew increasingly wary, convinced that the west, especially the United States, would never treat Russia as an equal and take its interests properly into account.

The continued expansion of NATO against Russia’s vehement protests was the most graphic – and in Putin’s mind most worrisome and threatening – evidence of that mindset. A decade ago, at the time of the (anti-Russian in Putin’s view) Orange Revolution in Ukraine, he began to articulate his concerns publicly. The current Ukraine crisis marks the final rupture, as Putin has made clear that Russia intends to stand apart from the west, and at times in opposition, as a great power that pursues an independent foreign policy.

In these circumstances, the United States will be compelled to rethink its entire relationship with Russia. In particular, if relations are to improve, the case will have to be made for why such a rethink is in America’s interest. Part of that argument will surely be that Russia and the United States, as the two leading spacefaring nations and among the world’s leading scientific powers, could gain much by working together to meet the challenges of climate change, energy security and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and to take advantage of the opportunities for space exploration and technological advance.

But for the next few years at least those benefits will almost certainly take a back seat to reemerging geopolitical competition and mutual recriminations that the other side is responsible for the breakdown in relations.