Sex probably ‘works’ in zero gravity - in the mechanical sense, although the physics will be a little tricky because every action has an equal and opposite reaction. But nobody has ever had a zero gravity or low-gravity pregnancy and progressing from current knowledge levels to being able to successfully make babies in space will be a much trickier business, not just in terms of science, but from the perspective of scientific ethics. This is just one of the issues facing future human space settlements tackled by Kelly and Zack Weinersmith in their book A City on Mars and explored for ROOM in this short extract.

Imagine this. You’re informed there’s a drug that’s really fun, but that results in slow bone loss, major fluid shifts inside the body, renal stones, muscle weakness, dizziness, and eyeball damage. You might still take it if all the cool kids are doing it, but you’d be substantially more careful if you were carrying a baby in your body. Replace the drug with space and you understand why you shouldn’t quit birth control in orbit.

Space settlement enthusiasts envision a time in the near future when people will colonise space, the Moon and Mars. But for an enduring population we will need to overcome many challenges, key among which are microgravity and radiation and we will also need much more and much lengthier research into human reproduction and child development in space before we can consider starting families there.

Space settlement enthusiasts envision a time in the near future when people will colonise space, the Moon and Mars. But for an enduring population we will need to overcome many challenges, key among which are microgravity and radiation and we will also need much more and much lengthier research into human reproduction and child development in space before we can consider starting families there.

Space has potential negative effects at every stage. Sperm and eggs are subject to constant radiation well before anyone dons a ‘2suit’ (one of several not-so-romantic concepts to hold couples together in the weightless environment). So is the resulting foetus, and the developing child, and the developing child’s gametes.

Microgravity is also frightening. On the one hand, a foetus is in a sort of miniature neutral buoyancy tank, so it’s possible the change in gravity regime wouldn’t have a huge effect on development in utero. In fact, according to the first Google result we could find, you can even do headstands while pregnant if for some reason you feel the need.

Acquiring the knowledge we need to have safe and ethical reproduction in space would be a massive, costly, decades-consuming affair.

Acquiring the knowledge we need to have safe and ethical reproduction in space would be a massive, costly, decades-consuming affair.

However, if any part of the developmental process relies on a consistent Earth-like downward tug, it will be disturbed off-world. Or maybe we’ll have to generate artificial gravity by spinning the station. This will be expensive, so an alternative could be to require mums-to-be to enjoy a centrifuge ride for the duration of pregnancy.

Creating new humans adapted specifically to hostile space environments far from the homeworld purely so they can settle it is morally dicey

Spinning provides the needed gravity, and expectant mums will never have to wonder whether or not they’ll experience morning sickness. And speaking of the privileges of giving life, remember that their bones will be weakened in microgravity and perhaps also under only partial Earth gravity. A serious open question is whether birthing is safe with a weakened pelvis.

For the baby, the time after birth is especially worrisome. The main current method of preserving bone health in astronauts is exercise, but you try getting a three-month-old to conduct resistance training for three hours a day. If you’re on the Moon or Mars, possibly you could employ a weighted 'onesie' to solve the problem, but because NASA has yet to spring for a lunar newborn, all we know now is that it’d be really cute.

We may at some point have drugs that halt bone loss in space, but whether we’re comfortable using them on children is a different matter. What we know about human bones in space today comes entirely from fully developed adults.

We have no knowledge about how altered gravity regimes will affect, say, a twelve-year-old girl having a growth spurt.

Another issue at every stage from conception to adolescence is hormones. For instance, there’s some evidence of hormonal changes in astronauts, such as lowered testosterone in males. The root cause may simply be stress from riding a giant exploding tube above the atmosphere and then working all day in a high-pressure environment. But we don’t know for sure, and once again, whatever the source of the problem, we only know its effects on fully grown adult males, not boys. Mars in particular may produce hormone problems. Martian soil is quite high in perchlorates, a class of chemical that messes with thyroid hormones.

Also, what kind of atmosphere are we raising our kids in here? If your settlement is like the International Space Station (ISS), it’s one with abnormally high carbon dioxide levels. That alone would be a novel environment for baby construction, but there may be other issues; when any new equipment goes to the ISS, it has to be carefully checked for what volatile organic compounds it emits. Think about it this way - when a new computer arrives at your house, fresh from the factory, you don’t really care if a bunch of weird synthetic gases waft out. You just think to yourself, “Good thing I don’t live in a tiny sealed atmosphere!” and go on with your day.

NASA keeps a list of what are called SMACs – spacecraft maximum allowable concentrations. These are how long you’re allowed to be exposed to various compounds in a spacecraft. For instance, if you’re only exposed for an hour, the atmosphere can contain up to 425 parts per million carbon monoxide. Bump that to twenty-four hours and you’re only allowed 100 parts per million.

If you’re staying beyond a thousand days, it drops to 15, which is about what you would find in the kitchen of a house with a gas stove. Why not just always keep things in Earth range? Because it’s more expensive.

Developing strong bones will be a problem in a reduced gravity environment. Getting babies to exercise for the required amount of time would be impossible. A weighted 'onesie' is one possible solution for babies. We don't know if it would work but it would be really cute.

Developing strong bones will be a problem in a reduced gravity environment. Getting babies to exercise for the required amount of time would be impossible. A weighted 'onesie' is one possible solution for babies. We don't know if it would work but it would be really cute.

A complaint made by astronauts Scott Kelly and Terry Virts regarding their time on the ISS, which would also be familiar to people who work in submarines, is the high level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which can lead to headaches. Keeping SMACs at a reasonable level is a tricky business, especially when, as one paper (M Sorek-Hamer & M Meyer, 2019) laments, “Earth-based [Air Quality Indexes] cannot be extrapolated to microgravity indoor environments.”

Some space simulations can be done on Earth, but it turns out simulating altered gravity is really hard

Now, take all of the above, and add to it that nobody’s been in a spacecraft for more than about 1.3 years consecutively, and you can see why, when it comes to safely making babies in space, the answer to most questions is a very, very, nervous shrug.

In fairness to those who are more gung-ho, we should remember that in the 1950s, some scientists worried humans couldn’t survive in microgravity, period. Maybe reproduction will be similarly benign.

That said, one difference is that if we’re just trying to verify nondeath, sending up a dog or ape for a little while is a pretty good test. Verifying successful childbirth and development is much more complex. Not only is it harder to test, but if humans do have major reproductive issues off-world, it’ll be extremely hard to know why. Suppose tomorrow you had a Martian settlement and observed a rate of developmental abnormality that was three times normal. Where would you point the finger?

Maybe it’s the altered gravity or maybe it’s the radiation. Maybe it’s the radiation but only in concert with an altered microbiome and the stress of trying to survive in a hostile environment. Maybe it’s some ultra-low-concentration SMAC gas nobody’s paying enough attention to. And if you’re talking about a child conceived and born in space, you also have to think about time - did the problem arise in the parents’ gametes, in utero, sometime after birth, or what?

If our goal is to have generations of 'space babies', it won't be enough to show that conception and birth are possible - we will need to know those babies can grow up to have their own babies.

If our goal is to have generations of 'space babies', it won't be enough to show that conception and birth are possible - we will need to know those babies can grow up to have their own babies.

Why don’t we know more?

Studying reproduction in space is hard to do, expensive, and it’s not like the ISS was set up to be a nursery. Also, space agency culture, especially in the United States, has been squeamish about exploring these sorts of questions.

Unfortunately, the work done to date is not the least bit systematic - it’s been done on different creatures, in different setups, with different protocols, for different lengths of time. The one thing these experiments have in common is that they aren’t run for long enough to be useful for the study of space settlements. If the goal is generations in space, it’s not enough to show that conception and birth are possible - we need to know those babies can grow up to have their own babies. We know of no studies on mammals in space where the process was observed from conception through birth, let alone development and conception in the following generation.

Some space simulations can be done on Earth, but it turns out simulating altered gravity is really hard. Experiments in space have similar problems. Launching to orbit means high acceleration with vibrations, followed by floating. If you’re a rat, you don’t even know why any of this is happening, and stress can produce weird physiological results.

For example, early on, researchers thought mice might not experience oestrous cycles in space, but it turns out in longer experiments, when you examine the mice before they’re brought back down to Earth, they do. Plausibly this is because they’ve been up there long enough to get used to the new environment and haven’t been stressed out by falling back to Earth, but we need to know more.

While we don’t have systematic or long-term data, what we can say is that the available experiments indicate that there’s not a chance in hell we would want to try having and raising kids in space.

Experiments show that radiation causes havoc for gametes and that microgravity may damage cell cytoskeletons. In case you don’t remember high school biology, these are the structures in a cell that give the cell its shape, kind of like the wooden beams in the walls that hold up a house.

Experiments involving creatures like tadpoles, salamanders, geckos, newts, quail (eggs), rats, and mice have found results like increased rates of abnormality, unusual swimming patterns, unusually large heads, unusually long tails, increases in infant mortality, decreases in oxytocin (an important hormone for birthing and bonding), and in one case an entire rat litter was stillborn due to a single abnormally large pup that wouldn’t fit through the mother’s birth canal.

But there are also studies where things went well. And there are studies where abnormalities early in development went away a little later. And this is why it’s such a problem that no sustained, long-term studies are happening: maybe there is some stage in the reproductive cycle that is irreparably damaged by the space environment, or maybe bodies can compensate for the space environment and be totally fine in the end. We just don’t know yet.

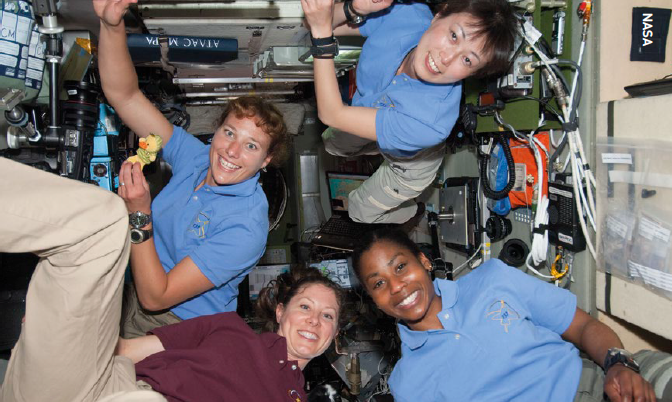

Astronauts (clockwise from lower left) Tracy Caldwell Dyson, Dorothy Metcalf-Lindenburger, Naoko Yamazaki and Stephanie Wilson aboard the International Space Station in 2010.

Astronauts (clockwise from lower left) Tracy Caldwell Dyson, Dorothy Metcalf-Lindenburger, Naoko Yamazaki and Stephanie Wilson aboard the International Space Station in 2010.

And will any of this apply to humans? We don’t know that either. A number of human women have become astronauts and then returned to have children. They often required assisted reproduction technology. Men, too, but male gametes are replenished over time and theirs are not the bodies in which babies are being created.

We’ve repeatedly encountered space-settlement enthusiasts who believe that because we don’t know whether there’s a problem, we should assume it’s okay

However, there’s a more boring reason for this than space travel: age. The average age at which women astronauts first go to space is 38, and these women typically wait to have children until after their flights are complete.

On the plus side, astronaut mums were not more likely to have spontaneous abortions relative to comparably aged non-astro mums. That’s good news overall, but because sexism is the gift that keeps on giving, a grand total of seventy-five women have ever gone to space as of this writing. There just isn’t a lot of data to work with.

We wish we could say more, but it’s hard to have much confidence in anything pertaining to having babies off-world. We’ve repeatedly encountered space-settlement enthusiasts who believe that because we don’t know whether there’s a problem, we should assume it’s okay.

Given what we know about space medicine and what little we can say from animal reproduction involving space, we think this is insane. Any space-settlement plan that doesn’t at least try to account for this stuff should be considered to have a major gap in research.

“Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise your kids”, sang Elton John. Strangely, in his song Rocket Man, he didn’t mention the potential for pelvic fracture during labour or the need to be centrifuged while pregnant. Such is poetic license.

The truth is we don’t know if he was right or not, and we don’t seem likely to find out soon. If you really wanted to know whether humans can have babies in space, the best experiment would be something like taking over a whole ISS module and dedicating it to a rodent colony that could be observed through a series of generations.

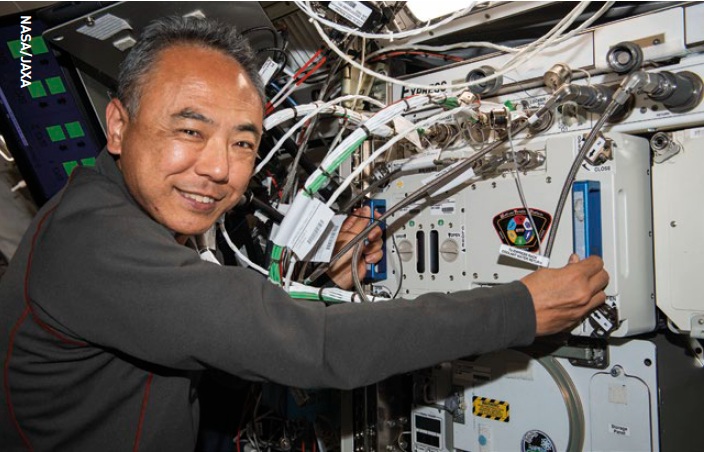

The most relevant, highest-quality project on the ISS today is likely MARS - the Multiple Artificial-gravity Research System. Run by the Japanese space agency, JAXA, it is able to simulate gravity. But even that system doesn’t simulate all the problems of particular space locations, such as Martian toxins or lunar levels of radiation.

We are not saying that any of this is impossible to solve. But as with space medicine generally, getting the knowledge we’d need to have reproduction in space that is safe and ethical would be a massive, costly, decades-consuming affair, and strangely, among people advocating for vast space settlements in the next 30 years, nobody is doing the sort of enormous spending necessary to get answers.

Adult humans can consent to be in experiments. Babies can’t. Electively putting a child in a space environment should only happen after we have a lot of positive data from other organisms. Ideally, this would at some point involve something like a primate centre in space, complete with a monkey day-care centre. This will be very expensive and very time-consuming and of course comes with its own ethical considerations. If there is no urgent reason to settle space, what is the ethical justification for a huge number of experiments on animals, including humans too young to consent?

Space sex and the consequences thereof

More importantly, we think the ethical costs are potentially tremendous. Bioethicists already debate whether it’s appropriate to develop ‘designer babies,’ but it seems pretty straightforward to us that creating new humans adapted specifically to hostile space environments far from the homeworld purely so they can settle it is morally dicey.

Just getting to the stage where such a thing would be possible is hard to imagine without a long series of genetic experiments, with questionable medical value, done on babies. If there were some kind of extreme urgency for human migration to Mars, perhaps this sort of thing could be argued for. But there isn’t.

When we talk about populations and growth in human settlements, we often talk at a high level, with humans as ecological and economic inputs - as statistics for a settlement strategy

When we talk about populations and growth in human settlements, we often talk at a high level, with humans as ecological and economic inputs - as statistics for a settlement strategy.

If your goal is to produce a lot of babies rapidly in an environment apt to create medical problems, the likely result will be a nontrivial population of children not adapted to the harsh and demanding environment. You may have kids who have physical or cognitive disabilities that mean they can’t contribute at the level of non-disabled children.

You may have kids who, for whatever hard-to-suss-out reason, have difficulty psychologically thriving in a confined unearthly environment. How do space-settlement enthusiasts react to these hard questions? As far as we’ve found, most don’t bother to deal with them. Those who do often possess a surprising level of banality about the likely consequences.

Space anthropologist Cameron Smith, who we genuinely consider one of the smartest voices in space social science, argues that a space society may favour evolutionary adaptation. As he says, you could have a culture that will endure the “painful transition” required to “allow natural selection to tailor individuals to their new environments.”

Alexander Layendecker, one of the best-known researchers on human sexuality in space writes, “if we cease to exist as a species, the deliberation of morality and philosophy issues becomes a moot point. Historically, the human drive for survival has a way of displacing morality and ethics in times of desperation.”

Perhaps most openly there is Konrad Szocik, a philosopher specialising in the ethics of space exploration. In a 2018 paper, he and his co-authors write, “The idea to protect life at every stage of development may not be suited to a Mars colony.”

In the same paper, they argue, “We assume that the Martian colony environment would favour these liberal proabortion policy [sic] because the birth of a disabled child would be highly detrimental to the colony... A Martian community may set new or higher criteria for valuable offspring, and may evolve to favour the preservation of personal and physiological traits more suitable to Martian residents.”

Now if, say, we were talking about humans marooned on a small island for generations, they might indeed develop norms and institutions that would have previously been considered morally questionable. The difference is that in the case of a space settlement, we are making a choice with full knowledge of the danger and potential consequences. If someone has a plan to send one hundred people to live stranded in Antarctica, and the plan notes that the Antarcticans might develop a culture that sees morality pertaining to disabled children as moot, your response won’t be “neato!” it’ll be “DO NOT SEND THEM!”

JAXA astronaut Satoshi Furukawa removes experiment hardware from inside the Multi-use Variable-g Platform, a biology research device that can generate artificial gravity inside the International Space Station’s Kibo laboratory module.

JAXA astronaut Satoshi Furukawa removes experiment hardware from inside the Multi-use Variable-g Platform, a biology research device that can generate artificial gravity inside the International Space Station’s Kibo laboratory module.

For many people who envision a Martian city, the entire project is wrapped in human aspiration - a chance to make humanity better with a new start. But if the new start requires us to create a new ethical framework that is anathema to most living Earthlings, then what’s the point? Note well, this problem isn’t just for the settlers and their children. If you accept political scientist Daniel Deudney’s argument that a large human presence in space gives us a lot of power to destroy ourselves, you should think twice about creating settlements where you anticipate the culture will place a low value on human life.

This article, published with permission, is based on an edited extract from A City On Mars - Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith, published by Penguin Press, New York (2024). ISBN 9781984881724. It can be purchased online and at bookshops.

This article, published with permission, is based on an edited extract from A City On Mars - Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith, published by Penguin Press, New York (2024). ISBN 9781984881724. It can be purchased online and at bookshops.

Going big

If there really isn’t an urgent reason to get a million people to Mars, there’s a good case for a wait-and-go-big approach to settlement

Here’s our overall take: everything about reproduction in space is cause for concern. This doesn’t mean we can never settle space, but it does argue against certain paths. Many space-settlement proposals call for a bootstrapping approach, in which you start with a minimal base, and then each landing facilitates the next, allowing for exponential growth of the settlement population.

It’s possible this would be the quickest way to grow a population, but if there really isn’t an urgent reason to get a million people to Mars, there’s a good case for a wait-and-go-big approach to settlement.

The idea is basically this: First, wait until you have the data and technology you need to safely and ethically move forward. Second, if you do try to build a space settlement, you’d be better off in a situation where you can settle a very large number of humans during just a few years.

This is a long way off technologically, but the advantages are very clear in a medical context. More population means more specialisation - more people specifically doing medical work. It also means that society has enough care workers and redundancy that nobody would ever have to say of a child that evolution needs to run its course on them.

People living on Mars may encounter any number of health issues including hormone problems. Martian soil is quite high in perchlorates, a class of chemical that messes with thyroid hormones.

People living on Mars may encounter any number of health issues including hormone problems. Martian soil is quite high in perchlorates, a class of chemical that messes with thyroid hormones.

If current technology barely permits survival and only permits natural population growth via throwing conventional moral standards out the window, and if there’s no reason to leave right this second, why not be patient? Spend at least a few decades working to advance the science of human reproduction, as well as every other technology relevant to space settlement. Then, we can send a population large enough and with advanced enough technology that we aren’t required to ‘set new or higher criteria for valuable offspring’.

About the authors

Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith are co-authors of the New York Times bestsellers, Soonish and A City on Mars, the latter receiving a Hugo, the Royal Society Trivedi Book Prize, and The Odyssey Award from the Earthlight Foundation in 2024. Dr Kelly Weinersmith is adjunct faculty in the BioSciences Department at Rice University, Houston, Texas, and Zach Weinersmith is the creator of the popular webcomic, Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal.