Active debris removal and on-orbit servicing are currently hot topics across the global space community. In this article Yolanda Kalogirou discusses the important issue of consent under international law in the context of the United Nations Charter and the Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (ARSIWA).

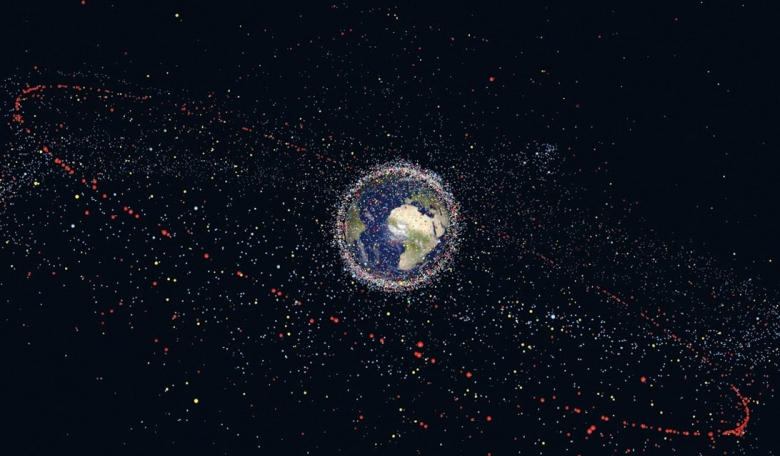

The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), states that 1400 objects in Earth orbit are functional satellites and 17,600 non-functional. The latter fall under the what is commonly referred to as space debris which, despite the lack of an accepted legal definition, has been defined in the guidelines of the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) as “all man-made objects including fragments and elements thereof, in Earth orbit or re-entering the atmosphere, that are non-functional”.

These space debris objects pose a serious threat to other satellites in orbit and there have been several documented incidents where debris was deemed to have caused damage to functional satellites.

One of the most prominent examples is a collision with Europe’s Sentinel-1A radar satellite that occurred in August 2016. As the European Space Agency (ESA) reported, a tiny piece of space debris hit its solar panels, causing a slight decrease in power and a change in the satellite’s orientation and orbit.

Space debris mitigation has for years been the main concern of the participating delegations of both the Technical and Legal Subcommittees of UNOOSA, and has resulted in the so-called Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines, endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly in Resolution 62/217 back in December 2007.