While we hear a lot about billionaire space entrepreneurs in the United States and Europe, most people have limited knowledge about the rapid space advancements now taking place within China. Here, Josephine Millward examines China’s space strategy, technological progress and the country’s nascent but rapidly growing commercial sector. As a space technology investor and former Wall Street defence analyst, Ms Millward expects US and allied government spending on space to remain robust in the coming years, driven by a new space race and rising geopolitical tension. A study by the US Defense Innovation Unit, Space Force and Air Force warns that China is on track to outpace the US by 2045 to become the dominant space power and displace the US as world economic leader. Both China and Russia view space superiority as key to success in modern warfare and have developed counterspace capabilities that pose a threat to the security of US and allies. In addition, space has becoming more crowded, and satellites are vulnerable to interference. Space has become a contested and potentially war fighting domain with the US, NATO and others standing up space forces and growing budgets to invest in new technology innovations. This article provides an overview of the US Space Force’s mission priorities and areas of technology interest in response to the growing threat environment.

The People’s Republic of China has emerged as an ambitious space power and it is on track to become the dominant economic and military force by 2045, surpassing Russia by 2030. Its space programme has made tremendous progress over the last few decades as a result of government policy prioritisation and execution of consistent and long-term plans.

China’s achievements are both significant and impressive. In 2003, it became the third country after the US and Russia to launch a human into space and has been expanding its space programmes ever since. China made history in 2019 when it became the first to land a spacecraft on the far side of the Moon. Last year, it successfully landed a rover on Mars. China completed the launch of its own satellite navigation system Beidou in 2020, which rivals the US Global Positioning Systems (GPS) with worldwide coverage. In 2022, China successfully completed the deployment of its own space station called Tiangong (Heavenly Palace) which, unlike the NASA-led International Space Station (ISS), is entirely built and run by China. It is expected to last 10 years.

China’s three-module space station witnessed a historic moment on 1 December 2022 when the Shenzhou-14 crew on board welcomed the three taikonauts of the Shenzhou-15 mission.

China’s three-module space station witnessed a historic moment on 1 December 2022 when the Shenzhou-14 crew on board welcomed the three taikonauts of the Shenzhou-15 mission.

Over the last decade, China has doubled its launches per year and number of satellites in orbit, and since 2018 it has surpassed the US as the country with the most annual launches - in 2021 alone it launched 55 missions. Furthermore, China is conducting historic space exploration missions and is racing the US to land humans on the Moon and ultimately to build a base on Mars for space resource extraction, a potential trillion-dollar market.

The People’s Republic of China has emerged as an ambitious space power and it is on track to become the dominant economic and military force by 2045, surpassing Russia by 2030

Make no mistake, today, China’s space programme is one of the fastest growing in the world and rapidly closing the gap with the US in terms of dominance and ambition. Less than 20 years after sending its first astronaut to space, the country has launched satellites, established a space station, sent rovers to Mars and the Moon, and plans to explore Jupiter by 2030.

As for the Chinese commercial space sector, this nascent but rapidly expanding industry began in 2014 backed by favourable policy decisions to promote innovation and efficiency. Prior to that, the Chinese space sector was entirely state-owned.

A year after Xi Jinping became the Chinese leader, the government issued a policy directive making space development a key area of innovation to enable large private investments. Supported by a robust civil space infrastructure and government funding, the Chinese commercial space ecosystem has flourished and now has between 150-200 companies. Between 2014 and 2020, Chinese space raised approximately ¥33 billion (US $4.5 billion), according to Euroconsult.

What is unique in China, however, is that the commercial space industry remains under the influence of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). National strategies such as Military-Civil Fusion leverages civilian and commercial space research and development for military applications. The opaque ties between the commercial and civil sectors to the People’s Liberation Army fuels Washington’s concerns over using civilian facilities for spying. Citing security issues, the US Congress passed a law in 2011 banning NASA from collaborating with China and from joining the ISS.

The Chinese commercial space sector has a high upstream concentration in launch vehicles, satellite manufacturing and more recently satellite internet infrastructure, the development of which is being driven by policy guidance. Many leading Chinese space start-ups are spinoffs from state-owned entities or have significant state heritage from two major state-owned entities, namely the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) and the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC), which focus on launch and satellite manufacturing, respectively. Given most start-ups’ have state heritage, these companies tend to be less global and have initially focused primarily on China’s large domestic market. However, as competitive pressures mount, the ambitious start-ups are starting to look to overseas markets, in particular in emerging markets.

Long March 2F Y15 with Shenzhou 15 atop rolling to the launch pad at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre.

Long March 2F Y15 with Shenzhou 15 atop rolling to the launch pad at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre.

Leading Chinese space start-ups include companies like Galactic Energy, a commercial launcher founded in February 2018 which became the first Chinese private launch provider to succeed in its first three launches to orbit this year. It is now building its Ceres rocket to offer rapid launch service for single payloads, while its Pallas rocket is being built to deploy entire constellations.

Rival company iSpace, formed in 2016, became the first commercial Chinese company to make it to space with its Hyperbola-1 in July 2019. However, iSpace had its third consecutive launch failure in 2022. It wants to pursue reusable first-stage boosters that can land vertically, like those from SpaceX. So does LinkSpace (founded in 2014), although it also hopes to use rockets to deliver packages from one terrestrial location to another.

Spacety, a small satellite company, founded in 2016, wants to turn around customer orders to build and launch its small satellites in just six months, and provide Satellite as a Service. Spacety is deploying a unique Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) constellation with both C and X-band images to enable new applications, including 3D reconstructions of terrestrial landscapes. The first images released from its satellite, Hisea-1, feature three-metre resolution. Spacety wants to launch a constellation of these satellites to offer high-quality imaging at low cost.

Another example is MinoSpace, a satellite manufacturer focused on developing platforms and payloads for its clients. The payload for the first Chinese private orbital launch attempt was developed by MinoSpac.

There are an increasing number of Chinese commercial companies planning low Earth orbit constellations in areas including remote sensing, communications, Automatic Identification System (AIS) and Internet of Things (IoT) satellites. These include Commsat, Linksure, ADA Space, Space OK, Laserfleet, Changguang Satellite Co. Ltd., Zhuhai Orbita, ZeroG Lab and Head Aerospace.

International market influence

China’s space programme is one of the fastest growing in the world and rapidly closing the gap with the US in terms of dominance and ambition

Central to China’s space strategy is an emphasis on international collaboration. In spite of the ban from working with NASA and ISS, China opened its space station to all UN member states and has so far signed 149 space cooperation agreements or memorandums of understanding, with 46 national space agencies and four international organisations. China has also leveraged the success of its civilian space programmes to partner and collaborate with the other space powers, including Russia and the European Space Agency, on scientific missions.

The primary focus of China’s space outreach has been in the developing world. China is leveraging space for diplomacy while tapping into large future markets. It has sold low-cost commercial satellites to several countries and offered others money, training and tech to launch their own. Between 2007 and 2018, China launched 20 satellites for 13 countries (Algeria, Argentina, Belarus, Bolivia, France, Indonesia, Laos, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Venezuela).

As part of the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative, China is building trillions of dollars of infrastructure from Asia to Africa to Europe, involving roughly 70 countries, building railways, ports and energy projects, all of which involves a ‘Spatial Information Corridor’ using remote sensing for sustainable development, in addition to China’s own network of Beidou navigation and positioning satellites. This raises concerns about the network of space infrastructure around the world potentially under Chinese influence. China has downplayed other aspects of its space ambitions, including its interest in space mining and applications.

Chinese scientists working on experimental cabinets, eight of which are installed inside Mengtian, the second lab module of China’s space station. They support in-orbit experiments on fluids, materials, combustion and basic physics.

Chinese scientists working on experimental cabinets, eight of which are installed inside Mengtian, the second lab module of China’s space station. They support in-orbit experiments on fluids, materials, combustion and basic physics.

Rising geopolitical tension

As detailed in the US Defense Intelligence Agency report ‘Challenges to Security in Space - 2022’ released in April this year, China and Russia have made tremendous efforts to establish space forces and expand space weapons capabilities, contributing to the increased militarisation of space. Both countries have active counterspace programmes and have developed robust and capable space services.

Chinese and Russian doctrine indicates that they view space as a requirement for winning modern wars. Under President Xi Jingping, China has designated space as a military domain, with official documents stating that the goal of space warfare and operations is to achieve superiority using both offensive and defensive means.

Since early 2019, China and Russia have increased their in-orbit assets by 70 percent across all major categories, including communications, remote sensing, aviation and science & technology demonstration, following a 200 percent increase in the three-year period from 2015.

China has been developing and testing anti-satellite weapons that could take down adversary satellites in low and high orbits. Counterspace weapons already pose a threat today on-orbit. In 2007, China conducted an anti-satellite missile (ASAT) test and the world is still tracking orbital debris generated from it. More troubling is that President Xi recently secured an unprecedented third five-year leadership term, making him China’s most powerful ruler since Mao Zedong.

According to a recent US Space Force briefing, the most likely threats today in space could be cyber-attacks targeting ground communications terminals, wiping out command and control, or laser blinding remote sensing satellites flying over areas of interest and electric jamming of satellites. Other threats are kinetic ‘kill’ missiles and robotic mechanisms that mimic space debris removal.

The US National Space Defense Center (NSDC) provides threat-focused space domain awareness across the nation’s security space enterprise.

The US National Space Defense Center (NSDC) provides threat-focused space domain awareness across the nation’s security space enterprise.

Space Force priorities

Nations around the world spent $92 billion on the space sector in 2021, according to Euroconsult, with the US accounting for more than half of the spending. Roughly half of this went to civil space supporting NASA and commercial activities, while the other half went to defence.

China, Japan, France and Russia were the next four biggest spenders. US and allied defence spending is expected to grow as a result of rising geopolitical tension and rivalry between space powers.

The US Space Force budget grew nearly 40 percent to $24.5 billion in FY2023, while NATO recently set up a $1 billion Defense Tech Fund to invest in early stage space and AI start-ups. Below we review the US Space Force’s mission priority & technology areas of interests to help investors and entrepreneurs understand and navigate the market landscape and near-term demand drivers.

As competition grows, China and the US are accusing each other of militarising outer space

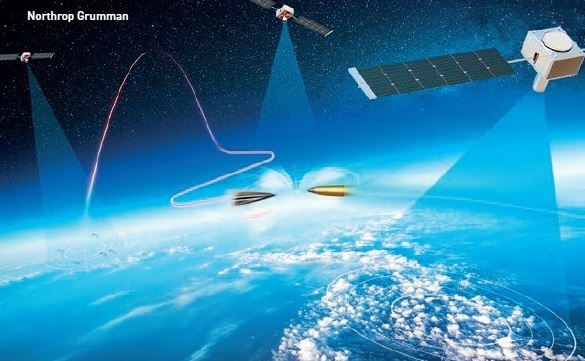

The highest priority mission for the US Space Force is missile warning and tracking. The next-generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (OPIR) satellites use infrared sensors to detect and track ballistic and hypersonic missiles. Next, the Space Development Agency’s plan to launch the Transport Layer or 126 communications satellites to support Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) capability, basically taking data from space and rapidly disseminating the information to air, land and sea. Resiliency is another top priority, which requires access to rapid launch and small satellite manufacturing capabilities that can rapidly replenish satellites on orbit.

Other mission areas and technology areas of interest include Space Domain Awareness, GPS and weather satellites, and data exploitation.

Space Domain Awareness: rapidly detect, warn, characterise, attribute and predict threats using high-capacity ground radars, detailed optical systems and space-based assets to maximise full characterisation. Low size, weight and power, on-board sensing technologies (objects and spectrum), on-board cyber protection elements, algorithms for autonomous satellite response, multi-object and non-Keplerian tracking algorithms.

Space Launch/Access: reduce cost and cycle time and launch on demand, high performance propulsion, enable reusable launch.

SATCOM: integrate communications across the US Department of Defense to form the combat cloud, layer Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) services onto every communications slink, develop laser communication system, develop V/W band radio frequency (RF) communications system. Build resilient and cyber secure ground infrastructure.

Alternative PNT: develop resilient (anti-jam signals) PNT, communications convergence, explore high gain antenna configuration, augmentation at geostationary and low Earth orbit.

In-Space Servicing/Assembly & Manufacturing: Refuelling, upgrade, manoeuvre, orbit transfer, satellite repositioning, debris removal.

Remote sensing/Tactical Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR): Cyber-secured using open standards and common platform that integrates capabilities across missions.

Weather: Launch demonstration satellites for weather imaging and cloud characterisation to either build the next-generation Electro-Optical Infrared Weather System (EWS) or buy weather data as a service. Provide critical data such as flight routes, combat search and rescue, maritime surfacing tracking, missile tracking and intelligence collection.

Analytics Products: Proof-of-concept Space Domain Awareness (SDA) marketplace for commercial data to enhance SDA. In the past, Space Domain Awareness was set up to track objects in orbit and issued collision warnings and was more of a global space traffic coordinator. Given space has become congested and contested, SDA is far more complex and requires all available data to analyse and characterise objects that are potential threats.

Technology advances have lowered barriers to entry and dramatically increased the number of space faring nations with satellites in orbit. The new space race of the early 21st century has increased the risk of operating in space with growing debris, congestion and anti-satellite weapons. At the same time, the competition is also sparking a new era of science and research, deep space exploration and international collaboration.

US defence system concept, called Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS), for counteracting threats from ballistic and hypersonic cruise missiles.

US defence system concept, called Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS), for counteracting threats from ballistic and hypersonic cruise missiles.

About the author

Josephine Millward is a partner at OpAmp Capital, a deep tech venture fund based in Washington DC, and a venture advisor to the Flying Object Fund, a sector-focused fund offering strategic capital to breakthrough solutions across the technology of flight and sustainability. She was previously a Strategic Advisor and Head of Research at Seraphim Capital, a leading SpaceTech VC that has backed more than 70 start-ups through its fund and accelerator. She has more than a decade of experience as a top-ranked Wall Street research analyst covering defence tech stocks.