Pseudo-satellites – officially known as High Altitude Platform Stations (HAPS) – offer rich potential for improvements in area-specific internet and telecommunications connectivity, while significant private investment capital has been attracted by the prospective commercial returns. The engineering-led focus of initial research and development has meant that the legal and regulatory framework to optimise their control and operation has been treated either as something that will be covered by existing provisions or by end-user demand. Increasingly frequent use of airspace at the operating altitudes of such equipment means that more detailed consideration will be necessary sooner rather than later.

It is clear that operations in the band of airspace between 20 km and 50 km above the Earth’s surface, known as higher airspace operations (HAO), is at an early ‘concept of operations’ stage in which there is general recognition of the need for further research. Unfortunately, as with many areas of space policy, this has led to stagnation. On the one hand, the understandable emphasis of private companies on product development and capability has tended to reduce law and regulation to an area of incidental concern. On the other, regulators risk lagging behind developing technical capabilities and becoming a ‘bottleneck’ that undermines international competitiveness, commercially and militarily.

Deciding the optimum legal and regulatory framework for such HAO would therefore benefit from a review of extant provisions, which may be characterised as a dichotomy between regulation of conventional aviation’s tropospheric or near-tropospheric operations, and the treaties applicable to ‘outer space’ activities.

Potential framework

The understandable emphasis of private companies on product development and capability has tended to reduce law and regulation to an area of incidental concern

Efforts to date have focused on what may provide an effective air and space traffic management system, but little significant progress is being made towards defining the optimum legal framework for the stratospheric airspace in which HAPS vehicles will operate. Indeed, the fact that the legal committee of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has not been tasked with conducting studies into how the applicable law should be structured suggests that creation of a new international treaty-based agreement is considered unnecessary.

In contrast, France’s higher defence studies institute has suggested three potentially suitable frameworks: space law; ‘tropospheric’ air law; or a hybrid framework unique to HAO. The scant substantive research by regulatory bodies like the UK CAA re-emphasises the need for closer consideration of whether the third potential ‘model’ may be preferable or risks introducing unnecessary complexity and cost.

Thales Alenia Space’s Stratobus airship can carry up to 250 kg of payload, its electric engines flying against the breeze to hold itself in position, and relying on fuel cells at night.

Thales Alenia Space’s Stratobus airship can carry up to 250 kg of payload, its electric engines flying against the breeze to hold itself in position, and relying on fuel cells at night.

A number of developments justify a careful review of what type of legal framework might optimise the balancing of the complex array of juxtaposed but substantially differing vehicle characteristics and operations currently under development. These include the likely return of supersonic transport aircraft (SSTs), the emergence of sub-orbital hypersonic transport vehicles (HSTs) using ‘scramjet’ propulsion, the growth of sub-orbital space tourism and expanding interest in commercial and state-sponsored satellite operations.

Technological innovation has enabled the development of air and space vehicles capable of operations at stratospheric levels that promise to deliver a wide range of services of potential benefit to humanity, all demanding their place in the HAO ‘space’. These include ultra-light, solar-powered, fixed wing HAPS vehicles, designed to operate at altitude around 20–25 km and capable of staying aloft for months at a time. They form an important part of the picture and promise greatly improved access to telecommunications services, including internet, in remote and less developed locations.

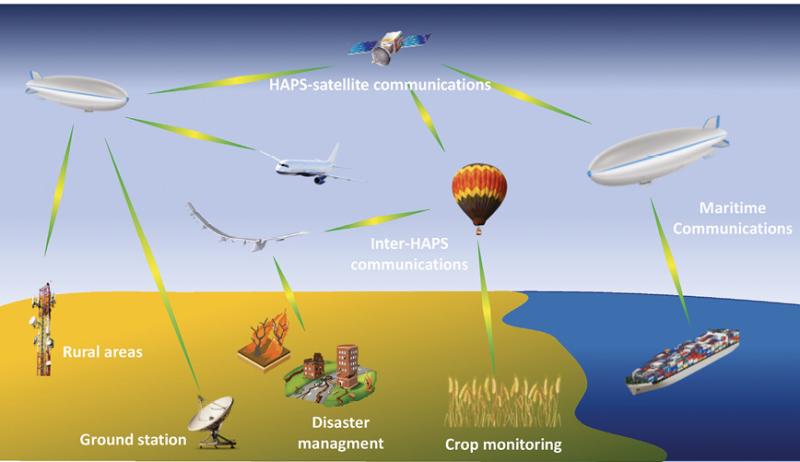

In mountainous terrain, this promises more cost-effective access than satellite technology, with improved internet connectivity due to lower signal delay, which affects the time from user input to receipt of server response. Compared to the 70 millisecond latency associated with low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite systems like OneWeb, HAPS promises latency times of a few milliseconds (ms). This stands to benefit uses as diverse as communications, disaster relief coordination, precision agriculture, entertainment or gaming applications and the increasingly important Internet of Things (IoT), facilitating economic development and higher living standards in under-developed locations. Whereas 40-60 ms latency is generally considered acceptable, by operators of LEO satellite systems such as Starlink and Kuiper, such systems cannot compete with the area-specific signal strength, comprehensive reach and operational flexibility of HAPS systems.

Such developments will make more intensive use of HAO at atmospheric altitudes hitherto frequented only by occasional research balloons, military aircraft and space vehicles enroute to and returning from outer space. So, while there was little need historically for an effective HAO legal and regulatory framework, the likely demands of many emerging operators of vehicles expected to make more intensive use of the stratosphere has now increased debate on what form this should take.

A thorough review of current air and space law will assist by considering which of the recognised potential legal frameworks - ‘spatialist’ or ‘functionalist’, terrestrial or space law, or some ‘bespoke’ hybrid of the models - may provide the optimum structure to facilitate safe, sustainable and cost-effective access to HAO by a mix of aircraft and space vehicles with substantially different operational characteristics and purposes.

The aim must be to identify the form that can most effectively secure the promised range of benefits to humanity whilst enabling safe operation of numerous slow-moving High Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) vehicles like HAPS alongside high-speed SST, HST and sub-orbital vehicles with very limited manoeuvrability. Whether this should be based on mutually notified de-confliction data or conventional control is currently debated, with US agencies favouring the former.

Key stakeholders in this process will be prospective operators and manufacturers of HAO vehicles, and ICAO contracting states and regulators with an interest in facilitating the success of such industry whilst safeguarding public safety and national security. Stakeholders will therefore include companies such as AALTO/Airbus and Stratospheric Platforms in the UK; AeroVironment, Boom Supersonic, Boeing and Lockheed Martin in the USA; military organisations such as the UK MoD and US DoD; and aviation and space regulators such as ICAO, FAA, EASA, Eurocontrol and the UK Space Agency (UKSA).

Regulatory bodies have begun to consider the nature of related research that will be necessary: for example, whether existing treaty-based space law is either realistic or fit for purpose. Seemingly anachronistic ideals of peaceful international collaboration in the interests of all humanity have become strained by increasing militarisation and conduct in pursuit of national developmental and competitive advantage.

A high-altitude communications graphic depicting HAPS providing connectivity to ground users – including crop monitoring, disaster response and inter‑HAPS links – highlighting real‑world applications.

A high-altitude communications graphic depicting HAPS providing connectivity to ground users – including crop monitoring, disaster response and inter‑HAPS links – highlighting real‑world applications.

Definition issues

Technological innovation has enabled the development of air and space vehicles capable of operations at stratospheric levels that promise to deliver a wide range of services of potential benefit to humanity

Deciding how HAO should be defined, given the lack of international consensus on what level above the Earth’s surface should be considered the de facto boundary between the Earth’s atmosphere and outer space, represents a necessary early consideration. The emergence of technologies that stand to make more intense use of HAO will require clarification of the basis upon which vehicles transiting the stratosphere, for purposes that may include orbital and sub-orbital use of whatever is defined as ‘outer space’, may do so without compromising the safety and effectiveness of other users of the same space.

The Montreal Convention (for tropospheric aviation) is unlikely to provide adequate liability cover for the differing risk profile of prospective operations in this space, so such aspects of HAO contingency management must also be integral to any effective consideration of the optimum legal framework.

Whereas the law governing use of tropospheric aviation and space vehicle activities is generally treaty-based, the content and purpose of the treaties contrasts substantially between the two activity types.

The Chicago Convention of 1944 provides the multilateral treaty-based foundation for detailed standards and recommended procedures (SARPs) governing terrestrial aviation produced by ICAO, the UN’s specialist civil aviation agency. Further regulations may then be produced by member states at regional and national level, though these generally seek to ensure compliance with ICAO rules produced under the authority of the Convention.

In general, SARPs apply to operators of vehicles capable of operations in or close to the troposphere. Suggesting use of this as the framework for HAO implies that vehicles operating within the stratosphere but no higher, including HAPS, may be treated as a mere extension of conventional aviation, so distinguishing between such vehicles and those operating beyond whatever boundary is acknowledged with ‘outer space’. The functionalist implication is therefore that sub-orbital space tourism, orbital and extra-orbital space activity should be considered outside any such legislative framework.

Meanwhile, activities in what may be considered outer space are covered by the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which was arguably founded upon ideals not being honoured in practice: space activities expected to further mutual cooperation benefiting all humanity have increasingly involved competition and development of military capabilities designed to eliminate threats by or to satellite systems. ‘Primary source’ statements of law’s aspirations are therefore less useful to critical analysis than secondary sources like transcripts from national legislatures’ committee inquiries.

United States Congressional Committee meeting transcripts highlight the aggressive competitiveness encroaching into activities in ‘outer space’ that may also affect HAO. For example, the encroachment of a Chinese surveillance balloon into the USA’s high-level Class E airspace, in 2024, led to questions about the effectiveness of its regulation and control.

Related discussions have therefore considered potential use of HAPS vehicles in defence of territorial sovereignty and space-based systems estimated to be worth around $325 billion to the US economy. Such emphases suggest not only that HAPS systems are considered likely to have a relevance beyond the immediate economic and humanitarian benefits alluded to earlier, but also that the law governing prospective future use of the space such systems will occupy needs to combine acceptance of the militarisation of space and the need for effective defence of related assets with facilitation of the many benefits that emerging HAO vehicle capabilities promise to deliver.

Overall, this suggests that the ‘wild west’ view of the stratosphere as an effectively unregulated space must change, with a need to assign a clearer legal and regulatory structure to its management and control. Whether the form of that regulation should be an adaptation of extant space treaty law or developed along more fundamentally nationalistic lines will be the issue that research should seek to make recommendations on.

Outer space is increasingly considered a diplomatic hot zone, with some Chinese sources also reportedly referring to ‘airspace’ between 20 and 100 km as a “new battlefield in modern warfare”, key to national security. Given that much related Chinese research and development is considered field-leading, such statements and developments may catalyse efforts to define and develop HAO legal structures and capabilities in a manner redolent of the impact that Soviet development of Sputnik in the 1950s had on American investment in NASA and the Moon programme.

HAO regulation seems less likely to be based on existing space treaty law than on adoption or adaptation of extant conventional aviation regulation

As alluded to above, air and space law fall under different treaties and provisions with markedly different purposes: air law recognises national sovereignty over airspace and potential private proprietary interests and space law is predicated on the ideal that space is to be used freely and peacefully for the benefit of all humanity without national appropriation or claims of sovereignty. Each system has particular and contrasting legal requirements with regard to liability, registration and the safety and security of vehicles operating in the respective domains. Thus the absence of any agreed definition of the level above which outer space begins requires scrutiny.

Whereas the US military and NASA have defined this as 50 miles (around 80 km) it may be that the 100 km boundary recognised more widely will be preferable in defensive terms. The Karman line, above which a vehicle cannot depend on conventional atmospheric lift to stay aloft, was originally calculated at 84 km, so the US definition is closer to this physics-based definition.

The potential implications for defence policy are clear. Achieving effective international consensus regarding what model, spatialist (physical extent) or functionalist (vehicular operational purpose), should apply to HAO airspace will therefore be as important to furthering peace and security as to realising the commercial, economic and social benefits that a clear legal and regulatory system should facilitate. The ‘X-planes’ of the US military achieved such altitudes as early as the 1960s, for example, and now provide a basis for extending the operating area of stratospheric SSTs to overland areas.

The Airbus Zephyr S, a High Altitude Platform Station (HAPS), flew for more than 25 days on its maiden flight in 2018. HAPS float or fly high above conventional aircraft and offer continuous day and night coverage of the territory below. Target applications include search and rescue missions, disaster relief, environmental monitoring and agriculture.

The Airbus Zephyr S, a High Altitude Platform Station (HAPS), flew for more than 25 days on its maiden flight in 2018. HAPS float or fly high above conventional aircraft and offer continuous day and night coverage of the territory below. Target applications include search and rescue missions, disaster relief, environmental monitoring and agriculture.

Political realm

Realpolitik seems all but certain to override the anachronistic and high humanitarian ideals projected onto activities in ‘outer space’, however defined, such that HAO regulation seems less likely to be based on existing space treaty law than on adoption or adaptation of extant conventional aviation regulation, with its acknowledgement of national sovereignty over member states’ airspace. Measures capable of accommodating the limited manoeuvrability and operating space requirements of SST, HST and sub-orbital space tourism vehicles suggest that the ‘adaptation’ approach may be most appropriate.

Work to define an appropriate legal structure, capable of integrating widely differing use requirements, has hitherto been focused on concept of operations efforts like Eurocontrol’s joint ‘concept of operations’ (CONOPS) for the safe integration of conventional air traffic management and HAOs, ‘ECHO 2’, though this has itself acknowledged a need for further directed research. While its focus on control implementation may suggest that a functionalist approach is considered optimal, the risk that this may be the result of confirmation bias among this forum’s participants must be borne in mind.

Being international in nature, the detailed rules required to achieve effective global regulation and control of higher airspace must draw their authority from multilateral treaties defining states’ rights and obligations. Whilst most states comply with International Court of Justice (ICJ) decisions in treaty disputes over which it is accepted as having jurisdiction - as UN Charter Article 94(1) requires - there is no enforcement mechanism as such in international law.

States aggrieved at any failure to comply with obligations imposed by ICJ decisions may complain to the UN Security Council, which may itself make recommendations or decide measures to give effect to the ICJ judgment under UN Charter Article 94(2). Iran’s action against the USA for its alleged breach of the bilateral 1955 Treaty of Amity is illustrative of such action: Iran’s complaint concerned the USA’s re-implementation of Security Council-authorised sanctions for Iran’s breach of obligations under the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Any meaningful HAO legal framework will therefore inevitably depend on geopolitical pragmatism

The weaknesses of such measures include that acceptance of ICJ jurisdiction is voluntary, that jurisdiction may be challenged by preliminary objection, and Security Council consensus is rare. Its members may veto measures, and the major space powers are permanent members. In effect, the functional success of the 1944 Chicago Convention, and the associated ICAO SARPs defining the conduct of tropospheric aviation, therefore relates more to national economic self-interest in maintaining an effective, inter-operable civil air transport system than notional international legal enforceability.

Any meaningful HAO legal framework will therefore inevitably depend on geopolitical pragmatism. Nation states able to derogate from multi-lateral treaties with operators and states not considered safely compliant with ICAO SARPs can existentially threaten the economic viability of such states’ operators by exclusion from their sovereign airspace. However, such unilateral sanctions risk creating bilateral conflict and undermine the fundamental point of multilateral treaty-based systems. In a post-Trump ‘America first’ geopolitical landscape, achieving sufficient, timely international consensus regarding a bespoke treaty-based system capable of delivering non-contentious use of HAO space may prove challenging.

No solutions yet

Most bodies involved in early-stage work on the optimum form of legal and regulatory structure for HAO, including HAPS operation, acknowledge the need for further research. Whether that research will conclude that the need for effective defence and protection of national sovereignty favours a model closer to a de facto upward shifting of tropospheric aviation regulation, a lowering of the reach of the ideals of the Outer Space Treaty, or a bespoke HAO hybrid based upon functional or spatialist principles, remains to be seen.

The prize for developing an effective system, combining safeguarded international security and the anticipated economic and social benefits likely to accrue from greater HAO use intensity, promises to be worth the effort.

About the author

Stephen Carr-Baugh is an airline pilot and former RAF Officer who has been called to the Bar of England and Wales. His wide-ranging experience of the aviation industry includes operational flying as a civil and military pilot, air traffic and range safety control, and aviation regulatory policy management at the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA).