When we think of the Space Age, we tend to draw an immediate parallel between space exploration and age of exploration, making a comparison between Christopher Columbus and the Spanish Monarchs, which financed him, to today’s space agencies like NASA.

However, today we live in a ‘commercial’ Space Age which has far stronger parallels to the Dutch East India Company (VOC) which acted as an expansionist power for the Dutch Republic but was beholden to a council of 17 board members in Holland rather than direct governmental oversight.

This is not altogether very different from the myriad of billionaires that have risen over the past decade and a half in the space industry, with goals that would have been impossible during the Cold War and the 1990s. Turning to the VOC we can learn much about corporations acting in lieu of states and extending political and market territoriality, much like space mining may entail.

We can learn much about corporations acting in lieu of states and extending political and market territoriality, much like space mining may entail

Business leaders and companies endeavour to innovate new technology in areas that were once relegated to government policy and planning. Elon Musk has famously made no secret that his space company SpaceX has the goal of sending a crewed rocket to Mars in the coming decades.

Portrait of the Directors of the Dutch East India Company by Johan de Baen in 1682.

Portrait of the Directors of the Dutch East India Company by Johan de Baen in 1682.

Commercial leadership

The age of the state leading the way in scientific and technological development is ending - and the age of private commercial firms just beginning. Multinational corporations and billionaires are operating in tandem and outside of the direct oversight of governments.

The success of SpaceX in the vertical landing of its Falcon 9 rocket represented a dramatic achievement in the cost-cutting of space technology and activity. Musk himself called it a “critical achievement” for the humankind’s future in space, citing it as a first step towards the colonisation of Mars.

Similarly, Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin was the first to succeed in landing a complete rocket back in 2015. Bezos has continued to state an ambitious plan to manufacture products from raw materials in space. Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner hopes to be responsible for the first Earth-made probe to visit Alpha Centauri. And, attempting to capitalise on an untapped market valued in the trillions of dollars, the United States now has four companies that are developing the plans and technology to mine asteroids.

Google has invested in SpaceX and Google co-founder Larry Page was an early investor in Planetary Resources. Navain Jain, a multi-millionaire who made his fortune before the Dotcom bubble burst, is a founding partner of Moon Express, an American company which hopes to acquire rights to mine the Moon.

Drawing by S Fokke, and improved by J Smit, from the Dutch Maritime Museum showing a meeting between the directors of the VOC and the Stadtholder, or executive, of the Dutch Republic in 1771. Here they are discussing colonial and trade policy.

Drawing by S Fokke, and improved by J Smit, from the Dutch Maritime Museum showing a meeting between the directors of the VOC and the Stadtholder, or executive, of the Dutch Republic in 1771. Here they are discussing colonial and trade policy.

Google has also had a hand in the development of new space mining firms by offering the Google Luna X-PRIZE, a multi million-dollar prize for innovative plans and technology advancement in space mining applications, among other things. One could say that the new space industry is now at least partially led by a patrician class.

The VOC was a commercial upstart of its day, competing with traditional sprawling empires like that of the Spanish for commercial dominance. As it grew it became one of, if not the, most valuable companies in the history of the world and one of Europe’s most vicious expansionists.

It was the commercial hegemony of the early modern world, run by a clique of well established plutocrats in 1602 with the specific aim of bringing a new and lucrative market under their commercial control. The VOC dictated colonial policy to the states-general and came to be the predominant power in the East Indies at the expense of the older more traditional Spanish and Portuguese empires. In the Dutch colonial empire, the company was indistinguishable from the state because it was fully in control of all state business in the Pacific.

Closeup view of Falcon F9 first stage landing on specially converted barge at sea.

Closeup view of Falcon F9 first stage landing on specially converted barge at sea.

The men who made up the board of the VOC, and founded the companies that were eventually agglomerated within it - were equivalent to the billionaires of today. Amsterdam was the financial heart of Europe and the lynchpin of the recently formed credit market, much like New York.

Moreover, the control of colonial policy is another issue that may present itself should companies like Planetary Resources or SpaceX establish territorial holdings in outer space. As the Spanish empire overextended itself, declaring bankruptcy four times by the 1610s, Dutch commercial entities took over from Antwerp, Lisbon and Seville in trade and volume of wealth.

Prior to the launch of the Dutch colonial effort, Amsterdam was already Europe’s greatest entrepôt - dispersing imports from the Baltic, the New World and the Far East throughout Europe. Dutch cities like Amsterdam, Enkhuizen, and Rotterdam were a commercial force to be reckoned with, having taken on the Spanish Empire in the Eighty Years War.

The billionaire class of our digital age has repurposed vast wealth made in domestic markets and is using it to innovate in new and unknown territory

By the 1590s the United Provinces were the dominant force in the so called ‘rich trades’. This was the shipping of high value commodities - such as sugar from Brazil, spices like pepper from the Indies, and Chinese porcelain and silks all across Europe. Merchants in Amsterdam, which more and more represented the financial elite of northern and western Europe, used this money to begin to finance larger and more expansive trade missions across the world, eventually culminating in an empire that stretched from Java to Japan.

The dominance of the new market for luxury goods helped finance private merchants investing in long distance trade directly with the Indies. By 1601 there were over 14 different privately led fleets being sent from Holland to the East Indies, entirely funded by stock offerings and private fortunes. Dominance of new products and means of shipping built the fortunes that would invest in private company ships, armies, diplomats, fortresses, and the bedrock of the aggressive company empire.

The billionaire class of our digital age are like the VOC men in that they have re-purposed vast wealth made in domestic markets and are using that to innovate in new and unknown territory. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, for example, has poured money into his own space company, Blue Origin.

Balancing act

We are now at the point where the line between science fiction and real life is seeming more blurred. Celestial mining is now a very serious proposition - so much so that the US Congress has extended property rights into space and is writing new legal regulations for space activity.

With the passage of the US commercial space Launch Competitiveness Act in 2015, companies will be setting the agenda, much like the VOC’s board of directors dictated colonial and Imperial policy. The Space Act specifically encourage space mining, the partial acquisition of territory in space, and states that an American citizen is entitled to any resource they are able to remove from an asteroid.

In seeking to facilitate a pro-growth environment in space, the United States’ government is walking a fine line in avoiding Article II of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 (OST), which banned the appropriation of ‘celestial bodies’. It is true that Article IV of the OST states that governments are responsible for the oversight of non-governmental use of outer space - but as speakers at the recent Manfred-Lachs conference in Montreal, Canada, noted, the OST just did not foresee outer space as an area destined for commercial exploitation. The US Space Act is therefore causing much controversy and disagreement among space lawyers.

In this environment, the US Congress’ aforementioned unilateral act of declaring the legality of property rights is not just controversial, it is an act diametrically against the former state-led use of space in favour of the new commercial space industry. The extension of legal rights, which may or may not violate international law, has armed commercial actors who have the capacity to disrupt the status quo.

Larry Page, who co-founded Google in 1998, is a trustee of the X-PRIZE Foundation.

Larry Page, who co-founded Google in 1998, is a trustee of the X-PRIZE Foundation.

In the wake of the passage of the Space Act, Luxembourg has announced it will also pursue its own space mining corporation, welcoming companies from around the world. One such company, Deep Space Industries, has opened up its second office in Luxembourg city and is advising the government there on how to pursue a future in a commercialised space environment. Similarly, Australia recently began a review of its own civil space regulation: The Space Activities act of 1998, and The Space Activities Regulations of 2001.

In seeking to facilitate a pro-growth environment in space, the United States’ government is walking a fine line

To draw on a cynical analogy, if lawyers are corporate soldiers, then this act was not unlike the arming of the VOC’s private army. This army existed to acquire and protect property rights for the company in a part of the world where there was no identified market orthodoxy for respecting and trading territory. Not only did the VOC have its own army and armaments, it had its own diplomatic corps. All members of the VOC staff had to swear loyalty to the company before the Republic. The company was a well oiled top-down machine throughout the protracted and sometimes violent domestic political history of the Dutch republic.

Dutch governors where occasionally called ‘Viceroys’, a term also widely used to describe Spanish colonial governors. They held their domains on behalf of the monarchial government, a strong absolutist organisation, which could be redacted at a whim. The Dutch Viceroys were far less vulnerable to the government than their Spanish counterparts. They were given their position by the board of directors in Holland, known as the Heeren Zeventien. Their key mandate was to ensure profitability for the VOC, rather than any state policy or geopolitical goals. The VOC’s empire was essentially private, under a thin membrane of state sovereignty, only accountable to the government in an abstract sense. Dutch Viceroys were not ruling in the name of a monarch or a court, but in the name of the company which was located in a republic.

Google X-Prize board of directors and trustees - Larry Page is centre left.

Google X-Prize board of directors and trustees - Larry Page is centre left.

If we compare today’s space entrepreneurs with the Dutch VOC, there is a fear for many that if a strong independent company were to acquire the rights to extract resources from outer space, a similar scenario might emerge. Such a company would be adherent to its own board rather than a government. And, as noted above, some of the most world’s powerful men are already on the board of at least one space mining company, Planetary Resources.

Regulation challenge

The Dutch East India company created a class of super wealthy who dictated colonial and Asian policy. Could the same thing happen with a private mining corporation? Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries’ lobbyists essentially wrote the Space Competitiveness Act for the congressmen who supplied it.

The Commercial Spaceflight Federation which was set up by some of the most eminent names in the commercial space industry (ie, SpaceX, Blue Origin, Moon Express and Virgin Galactic), steers and is a growing and powerful lobby in Washington. The question must be asked, how could a country curtail the influence of a potentially trillion-dollar industry operating outside of Earth orbit, where oversight would be difficult and incredibly expensive?

During the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries when the Dutch Republic went to war against another European power, the VOC acted as an Asian surrogate against colonial rivals. In a theoretical conflict between space powers, what would the company’s position be, and how would it potentially defend itself?

With numerous nations pursuing space mining - including the United States, Luxembourg and Japan - as well as a redeveloping cold war between Russia and the United States, along with a very ambitious China in a three-way race for mastery of the ‘ultimate high ground’ (as Space has been referred to by America military leaders) this question has become all the more pertinent.

One can see that the private individuals who made vast fortunes in new domestic markets were the same men to see an opportunity in East Asian trade. Notably, these men were international and had no national or ideological loyalty to the Dutch republic by birth. Jan Poppen, for example, emigrated to Amsterdam from Holstein as Lubeck and Hamburg were overtaken by Holland in terms of wealth and financial sophistication.

The extension of legal rights, which may or may not violate international law, has armed commercial actors who have the capacity to disrupt the status quo

And while Christopher Columbus famously went from one royal court to another looking for financiers, the Dutch patrician class had no such problem because of the invention of the joint stock company and financial instruments like shares. The monarchial patron lost its monopoly on financing innovation as soon as the joint stock company allowed wealthy businessmen to share the bill.

In the same way, as space becomes profitable and open to private investment then, for-better-or-worse, the state will have a harder time regulating the global space industry because it will become a more and more powerful lobby. The VOC eventually declined because it was not being held accountable by the Republic’s government.

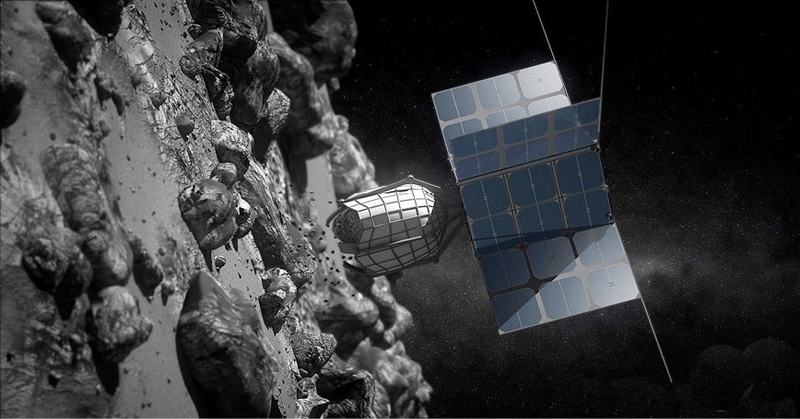

Concept for Deep Space Industrie is space mining Dragonfly vehicle.

Concept for Deep Space Industrie is space mining Dragonfly vehicle.

As with all analogies, this one between space mining and the early modern colonial period is imperfect. However, with the billionaire class and many companies such as Google wealthier than many states, we as a society must be aware of historical precedents as we enter space and extend the market’s reach into the void. As we observe these non-state actors on the periphery of traditional jurisdiction, we have this rich precedent to draw lessons from. The most important question, however, is how will private actors operating in new regions of human activity be held accountable for their conduct and expansionism?

Harris Innes-Miller is a political science undergraduate honours student at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. His studies include the history of economic crises, legal history, and the global arms industry with a speciality in commercial weapons and aerospace. His honours thesis is ‘The Political Economy of Classical Powers in the New Space Age: A comparison between the new organization of the American and Russian Space Industries’.