In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the world’s first artificial satellite from Baikonur Cosmodrome. Since then, space launch has been achieved from 28 spaceports around the globe, 22 of which remain active. Of a further possible 21 in the pipeline, it is safe to assume that not all will make it, in many cases due to budgetary constraints. The author casts a pragmatic eye over the process of making spaceports a reality.

There is no getting away from the fact that millions of dollars are needed to develop a spaceport and, in recent years, many writers have commented on these high costs. This article seeks to illustrate that, by challenging the status quo and deploying a carefully selected, experienced and expert team, a spaceport stands a better chance of success as it moves through funding rounds and gateway approvals.

Whilst value engineering comes with the territory, overzealous, unchallenged or immature requirements at the early appraisal stages can unnecessarily bring projects to a premature end.

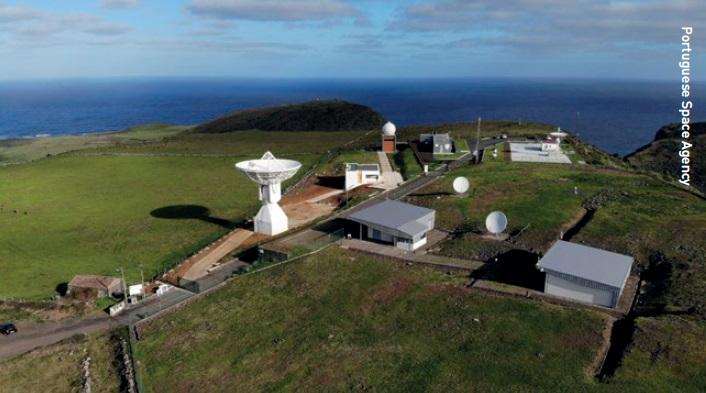

Santa Maria is the southernmost island of the Azores making it a prime location for a Portuguese spaceport with launches towards the south to LEO.

Santa Maria is the southernmost island of the Azores making it a prime location for a Portuguese spaceport with launches towards the south to LEO.

Andøya Spaceport in Norway opened for business on 2 November 2023, offering launch services to vehicles designed to deliver payloads of up to 1.5 tonnes, primarily using liquid fuel. Isar Aerospace will have exclusive access to the first launch site.

Andøya Spaceport in Norway opened for business on 2 November 2023, offering launch services to vehicles designed to deliver payloads of up to 1.5 tonnes, primarily using liquid fuel. Isar Aerospace will have exclusive access to the first launch site.

NewSpace solution?

NewSpace organisations face significant challenges in the journey from idea to orbit

Traditional space - sometimes referred to as ‘old space’ – is anecdotally associated with government-funded and government/contractor-operated spaceports, supported by billion-dollar prime contractors. Legacy launch sites, established by the USA and Russia over several decades, had a more straight forward journey during times when political emphasis for dominance in the space domain was used to sweep aside barriers to buying land and getting builders on the ground.

NewSpace is a concept that covers the opening up of a space economy to make it accessible to private companies and can be traced as far back as the 1990s. It is generally acknowledged to be the battleground of small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), startups and disruptors, which challenge the way of the old guard with a faster, leaner and profit-minded approach to space-related activity.

For example, the last decade has seen a noticeable increase in the development of micro launch companies, capitalising on the small satellite and Earth observation (EO) data market. There has also been a scramble for governments with no prior spaceflight heritage to develop sovereign launch capability, with that focus sharpening since February 2022.

Events in eastern Europe have provided clear evidence that there is no guaranteed access to other nations’ spaceports, but these NewSpace organisations face significant challenges in the journey from idea to orbit. Until recently, the knowledge and resource needed to develop a spaceflight capability resided with the prime contractors and government agencies. There were notable exceptions, of course, but more often than not a large aerospace or defence prime is usually somewhere in the supply chain, if not at the top.

These entities are well known as organisations that have serious launch heritage, are capable, knowledgeable and well resourced, but this capability comes at a cost. New entrants to the space community tend to arrive with a small team, are under-resourced, not adequately funded and need to demonstrate results quickly. Moreover, seed funding and Series A funding tends to be pushed towards technology development, which further compounds the difficulty to secure sufficient funds to build and license a spaceport.

As is true for any new business venture, being thrifty is a must, as is being agile, moving at pace and improvising. A new business simply cannot afford to be an overtly process-driven bureaucracy.

Primes are great businesses and thought leaders which have earned the utmost respect, but they are, by their nature, heavily process driven, so they struggle to match the tempo of a start-up or young business. Primes have large overheads and have a ‘bottom line’ that will need to be achieved to make a business with a small spaceport worthwhile. Coupled with the suggestion that the age-old art of ‘nickel and diming’ does not always come naturally to billion-dollar prime organisations, available funding may run out quickly.

Whether it is down to cost, agility, alignment of goals or clashing cultures, unless a new way is found to support and unlock future spaceports many will not get off the drawing board. Luckily, the NewSpace sector is evolving to demand a more efficient way of delivering its launch infrastructure and licensing needs.

In January 2023 the Hong Kong Aerospace Technology Group (HKATG), Touchroad International Holdings Group and the Government of Djibouti signed a joint agreement to build a Djibutian spaceport in the country’s northern Obock region launching to the east over the Gulf of Aden.

In January 2023 the Hong Kong Aerospace Technology Group (HKATG), Touchroad International Holdings Group and the Government of Djibouti signed a joint agreement to build a Djibutian spaceport in the country’s northern Obock region launching to the east over the Gulf of Aden.

Spaceport licensing

Unless we find a new way to support and unlock future spaceports, many will not get off the drawing board

The world of regulatory regimes that a spaceport operator will need to comply with is incredibly complex. It is, however, just another challenge in successfully delivering a spaceport. The list of regulated areas which the spaceport will need to navigate is extensive: spaceflight, aerodrome, airspace, environment, health and safety, transport, US Export Control and International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), the Export Administration Regulations (EAR), the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), building permits and planning and so on.

Countries new to spaceflight will likely either have introduced or be in the process of introducing regulations to govern space activity which will need to dovetail with existing regulations. All of these licenses and consents must be integrated and, because a change in one will ripple through to others, the consequences of the interdependencies must be understood and actively managed. Configuration control is therefore paramount.

One oversight or misunderstood dependency could have a profound effect on the project. All the larger organisations will offer a service to manage this complex process, but it is often resource-hungry with a timeline that could run for years. A further challenge is that any scope of work to manage this needs to be adaptive and be able to use resource and subject matter experts flexibly in reaction to changing demands.

As an alternatve to inviting in a larger contractor to undertake this work, clients are turning to a growing number of SME alternatives that are passionate and knowledgeable. They offer an agility and cost base that cannot be matched by large businesses. In essence, they can provide a tailored service, delivered swiftly and for a fraction of the cost when compared to larger, more established organisations.

This agile and SME mindset further extends to strategy, which translates to a dedicated team that will work at the tempo of the client and can deploy professional services as required, which all leads to a more desirable bottom line as costs can be controlled.

Italy’s first spaceport is to be built at Taranto Grottaglie Airport in Puglia. ‘Cryptaliae Spaceport’ will be specifically designed for the development of a spaceplane that is capable of travelling from one place to another using horizontal take-off and landing.

Italy’s first spaceport is to be built at Taranto Grottaglie Airport in Puglia. ‘Cryptaliae Spaceport’ will be specifically designed for the development of a spaceplane that is capable of travelling from one place to another using horizontal take-off and landing.

Challenge everything

The facilities must be future -proofed and designed in a way to allow them to be extended and enhanced without impacting day-to-day spaceport operations

Whether vertical launch or horizontal launch is under consideration, there are multiple options in terms of securing what one needs to successfully deliver those all-important first launches. In the same way as when someone starts up their own business, the first purchase is not a 50,000 sqft grade-A office in the middle of town; the kitchen table will suffice for the first few months until they know (a) what the business is going to look like in the next couple of years and (b) when the money will start coming through the door.

Clearly, not every part of a spaceport can be slimmed-down on the first day of business. Your launch pad or taxiway and apron may need to be as it will be for years to come, with its launch platform, deluge system, lightning masts, commodity storage areas, security, hard standings, fencings, access tracks, etc (and your range infrastructure likewise). It must be safe, secure, compliant and fit for purpose.

The most expensive elements of spaceport infrastructure will be the processing and integration facilities for the launch vehicles and payloads. This may include multiple cleanrooms and hangar space, plus the usual offices, meeting rooms, toilets, welfare, facilities and car parking. On a dollar per square foot basis, cleanrooms are the most expensive element of the build and, with energy costs remaining high and energy security uncertain, running costs and how the internal environments are achieved is becoming more of consideration when determining operational expenditure and lifetime costs.

For startups, the solution must be scalable and combined with real world experience in engineering vertical and horizontal spaceports to meet aggressive budgets and performance requirements. Every half metre in building height, every cleanroom classification, every floor finish, lighting level, air movement, kW of power, degree of temperature, kilogram of steel – every aspect is scrutinised to make the facilities as lean as possible. Moreover, the facilities must be futureproofed and designed in a way to allow them to be extended and enhanced without impacting day-to-day spaceport operations.

To enable the smaller launch sites to offer an attractive local alternative to ride-share operators, the launch system as a whole must be value driven. When the launch operator and the spaceport operator work collaboratively, with a like-minded support team, the results are not insignificant.

After working with multidisciplinary teams, largely consisting of SMEs, in the delivery of two spaceport programmes, it was evident to the author that there is a demand for a cost effective and agile team to provide dedicated support for such programmes globally. This is what is exciting about the Fire Arrow proposition, a network of experts with a proven track record of past collaboration to deliver horizontal and vertical launch spaceport programmes, from idea to orbit. The company’s unique selling point is its ‘concierge service’ for commercial and government clients, delivered, as outlined above, with a focus on increased responsiveness and minimised cost.

It is this NewSpace approach that the market requires to bring launch capability in line with other commercially driven segments from the value chain, together with an aligned focus on swift, responsive support and environmentally sustainable operations.

Rocket Lab offers the world’s only private orbital launch range in Mahia, New Zealand. An FAA-licensed spaceport, Launch Complex 1, can provide up to 120 launch opportunities every year.

Rocket Lab offers the world’s only private orbital launch range in Mahia, New Zealand. An FAA-licensed spaceport, Launch Complex 1, can provide up to 120 launch opportunities every year.

About the author

Stuart Fyvie MSc MCIOB is Technical Director of Fire Arrow Ltd. He has 25 years of experience in the construction and property sector and was previously a Partner of a global construction consultancy, delivering complex projects including spaceport delivery and programme management, satellite manufacturing and operations facilities. He is currently involved in the delivery of Sutherland Spaceport and Prestwick Spaceport inScotland and has a working knowledge of the complex regulatory environment within which launch activities need to navigate.