When Aarti Holla-Maini addressed 1500 delegates at the UK Space Conference in Belfast in November she had been Director of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs in Vienna for just a couple of months. Here she shares her thoughts on the future of space and asks what can be done to make better use of space to achieve policy objectives.

As an integral part of the United Nations, the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) has an unequivocal mandate for space. Its Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), which was most recently responsible the long-term sustainability guidelines, was historically the birthplace of the Outer Space Treaty (OST) and all of the principles, guidelines and resolutions on which today’s global space economy is built.

The office also assists Member States to put their own space laws into place, helping them launch and register satellites, and even training professionals in management agencies on how to access and use space data in times of disaster.

We run Access to Space4All programmes under which we help non-space faring nations launch their first satellites and a host of other thematic programmes and initiatives around Space4Women, Water, Climate, etc, designed to help countries, especially developing countries, access the benefits of space to accelerate sustainable development.

But one thing we don’t do as an office is tell our story well enough and I’d like to change that. At the same time, we really need that story to evolve, to be one that is directly relevant to our future - and here is why.

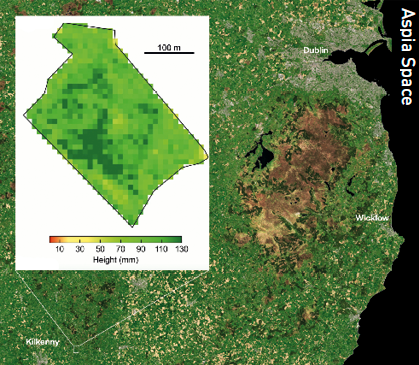

Origin Digital and Aspia Space launched ‘GrassMax’ in Ireland in 2023. AI-based technology estimates grass height to within an accuracy of just 15 cm from satellites nearly 700 km above the ground. The service enables businesses to track live and forecasted grass yield, how many days animals are at grass in the fields, and a host of other metrics targeted at increasing fertility, yield, and efficiency to meet the growing demand for milk and dairy products sustainably.

Origin Digital and Aspia Space launched ‘GrassMax’ in Ireland in 2023. AI-based technology estimates grass height to within an accuracy of just 15 cm from satellites nearly 700 km above the ground. The service enables businesses to track live and forecasted grass yield, how many days animals are at grass in the fields, and a host of other metrics targeted at increasing fertility, yield, and efficiency to meet the growing demand for milk and dairy products sustainably.

In October 2018 Peru became the first country in Latin America and the second in the world to release to the public the vessel monitoring system data (VMS) of its fishing vessels, through the Global Fishing Watch (GFW) platform, with the aim of tracking vessels and preventing illegal fishing. Other countries have since followed Peru’s example.

In October 2018 Peru became the first country in Latin America and the second in the world to release to the public the vessel monitoring system data (VMS) of its fishing vessels, through the Global Fishing Watch (GFW) platform, with the aim of tracking vessels and preventing illegal fishing. Other countries have since followed Peru’s example.

The UN is a champion of sustainable development and we are halfway through our journey to achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) but they still look like far away targets. We must accelerate our efforts to achieve them, leveraging space solutions to do so.

Space is not just an enabler of the SDGs, it is a major driver of them, and if that is the case the question I would ask is, are we proactively leveraging space and maximising it’s potential for our common future? Or are we waiting for companies to respond in areas where they see a commercial interest to do so?

Should we prioritise putting policy frameworks into place that incentivise and actually call upon space actors to address the world’s most pressing challenges?

For me, that is at the heart of this question of what space for our future truly is. We need to embed space into national, regional and global policymaking by design. The UK, for example, knows very well what it is to embed space into the fabric of policymaking. By demonstrating the value of its space sector to the economy the UK doubled its investment in the European Space Agency (ESA) and went on to establish the UK Space Agency (UKSA), as well as a dedicated Satellite Applications Catapult to fuel new innovations.

That is what it means to embed ‘space by design’ into the fabric of an economy. But I would invite you to think a little bit further than this. We are all affected by current global challenges. Climate change is one of them; political stability and security are others.

As much as it is in our interest to build national resilience against future shocks, be they from climate change or elsewhere, it is also very much in the interests of individual countries to ensure that those in the ‘global south’ are safe, healthy and have opportunities for their future. Otherwise, as we know, they will travel to those places where they think that they can find them and that disrupts lives and economies that may already be hanging in the balance.

So, the question that I would like to ask in the context of ‘Space for our Future’ is, should we prioritise putting policy frameworks into place that incentivise and actually call upon space actors to address the world’s most pressing challenges? Or should we just wait for the pursuit of economic return to align itself with the need to invest and deploy solutions that serve life on Earth and the planet itself?

Driving change

Today there are so many active examples of space technology, data, and services that are driving tangible change and many of them have come from the UK. But I believe that, if supported by appropriate policymaking, they have the chance to be leveraged at scale to drive results on global challenges and bring economic returns for those who are enabling them. I think this approach is in line with the four pillars of the UK National Space Strategy - Growth, International Collaboration, Science and Resilient capabilities.

Consider that in Ireland, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellites are being used to measure grass growth to support rotational grazing for farmers, which has significantly impacted profitability in a positive way. In the broader context we should remember that the UK imports nearly half of the food it consumes. Do we realise that 15 percent of that food is actually lost between farm and shop and almost a third of it is ‘lost’ in the local context?

Role of satellites

Do we realise that if a two-degree temperature increase happens, the global coffee supply may be reduced by half?

What role can a country like the UK play in pushing policies that mitigate these kind of risks? In my opinion, satellites have got a direct role to play in, for example, remote container management and in monitoring the chain from farm to fork.

Companies aren’t obliged to use these technologies, however. Precision farming equates to yield and therefore profit for farmers but not all farmers are ‘connected’.

Satellites can dramatically reduce international, unregulated and unreported fishing. This is a global problem but not every fishing vessel carries the necessary equipment and there is currently no global requirement to do so.

I recently spoke at an event in Costa Rica and gave the example of Peru where satellite technology is being deployed to monitor fishing and, by doing so, within the space of one year, illegal fishing vessels have been reduced from 300 to 40 and the losses of US$300 million a year dramatically reduced. Surely, we need more countries to implement similar laws? This is the kind of practical problem that, if we act on, could really drive global change.

Many of the Essential Climate Variables (ECVs) used to monitor climate change can only be measured from space. We wouldn’t even know that there is a climate crisis if we didn’t see it thanks to satellites gathering data from Earth orbit. Despite its obvious value in this respect, space was still a sideshow at the latest COP28 in December.

Governments and industry alike should also speed up efforts to implement voluntary guidelines for the sustainable use of space, rather than push for a new global treaty that will be difficult to conclude.

We need a multilateral process and as much collaboration as possible, because delivering a binding treaty at a time of global tensions and international rivalry in space will be contentious and take time. We have to be realistic - an agreement on all of the issues would be impossible to achieve at present.

However, the power lies with Member States. I would like to see national regulators accelerate the implementation of the UN Long-Term Sustainability guidelines issued in 2019. National implementation would greatly boost space sustainability which, as satellite services become critical to digital-based infrastructure, should be a priority for all countries.

Much of the content in the guidelines could be turned into norms, including proposals to manage activity in space safely, mitigate debris and share more data on the operation of satellites, anti-collision measures and weather patterns. Implementing the guidelines is the best chance we have of moving in the right direction.

Practical applications

Space is a key piece of the sustainable development puzzle that urgently needs slotting into place

How many people ‘need’ their coffee every day; isn’t that something to think about? Do we realise that if a two-degree temperature increase happens, apart from anything else, global coffee supply is going to be reduced by half? It may not always be the first thing we think about when sitting in a coffee shop, but satellites can help mitigate those risks.

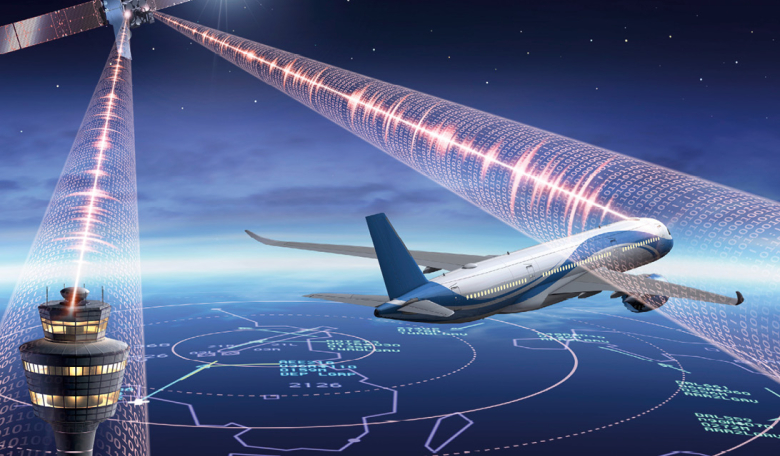

In terms of commercial flights, on average every European flight flies an extra 26 unnecessary miles, yet there is no global policy in place to ensure air traffic control systems change systemically to ensure the implementation of satellite solutions to prevent this waste and so help reduce the carbon emissions from aviation.

ESA’s IRIS programme, for example, aims to make aviation safer, greener and more efficient by developing a new satellite-based air-to-ground communication system for Air Traffic Management (ATM). It is being developed in conjunction with Inmarsat and by 2028 will enable full 4D trajectory management over airspaces across the globe with a data link acting as the primary means of communications between controllers and aircraft crews.

Such programmes, which directly link space technology with everyday applications, could play their part in helping eliminate those extra miles which would have a huge impact on global emissions.

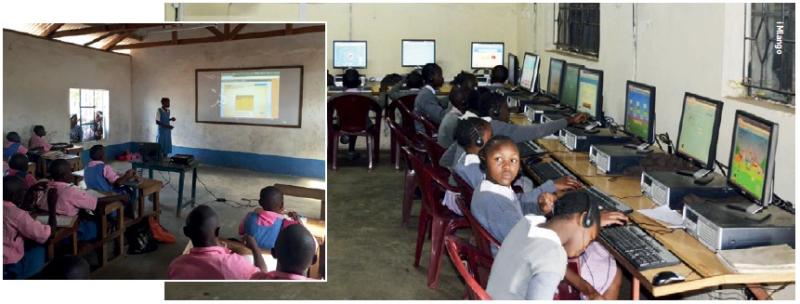

Elsewhere, whilst one UK satellite operator is helping educate marginalised girls across 245 rural and isolated schools, millions of girls worldwide are still uneducated and in poverty because there is no national, regional or globally targeted programme to use satellites to reach them. This is despite the fact that satellites have the capability to take people from zero connectivity to 3G or 4G within the space of a few months.

All of these examples require UNOOSA to collaborate with international organisations and other UN specialised agencies, but at the heart of them all are the Member States.

The UN can and should provide leadership but ultimately it is Member States that need to push these solutions.

iMlango is a comprehensive educational technology programme that aims to improve Kenyan pupils’ learning outcomes, enrolment and retention. It is delivered by UK satcoms company Avanti and its partners sQuid, Camara Education and Whizz Education working in partnership with the Kenyan and UK governments.

iMlango is a comprehensive educational technology programme that aims to improve Kenyan pupils’ learning outcomes, enrolment and retention. It is delivered by UK satcoms company Avanti and its partners sQuid, Camara Education and Whizz Education working in partnership with the Kenyan and UK governments.

Regulatory frameworks

UNOOSA needs to and wants to help with tangible results from space for our future, but that is a big challenge and one that will require strong and committed partners. We need innovation as part of this but what I think is really missing is the link between science and technology and policymaking.

We need to focus and accelerate with a sense of urgency. There are so many areas of need, whether we consider the digital divide or climate change. All these needs find a solution in satellite.

Unfortunately, there are gaps between demand for solutions and their supply. Those gaps are often the lack of an enabling regulatory framework, or the lack of political will or, quite simply, that policymakers have not yet realised that they need to act to bridge the gap between demand and supply.

There are plenty of use cases leveraging satellite solutions today. But are these efforts clearly visible? My answer is ‘no’! Do we tell our stories well enough? No!

Most of the examples I’ve given will be familiar especially to members of the space community. It is increasingly important that we scale them quickly to cover as many areas as possible. The science is there, and the technologies are there. Space is a key piece of the sustainable development puzzle that urgently needs slotting into place.

COPUOS seeks to develop space sustainability frameworks

COPUOS seeks to develop space sustainability frameworks

Editor’s note: This article is based on a keynote address given by the author at the UK Space Conference, Belfast, November 2023. Though a predominantly British audience her words have a wider resonance to the worldwide space community and governments at large.

About the author

Aarti Holla-Maini was appointed Director of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) in Vienna in June 2023 by UN Secretary-General António Guterres. Ms Holla-Maini has over 25 years of professional experience in the space sector including in managerial and advocacy functions. Most recently, she held the role of Executive Vice-President Sustainability, Policy & Impact at NorthStar Earth & Space, prior to which she spent over 18 years as Secretary-General of the Global Satellite Operators Association.