The space sector has evolved dramatically over the last 20 years, experiencing an increasingly diverse range of employment opportunities and requirements, which one could otherwise characterise as ‘disruptions’. Given that the space professional workforce will always be highly skilled, Jason Maroothynaden explains these disruptions from the viewpoints of employers and employees.

‘Earned’ media, which includes all the media activity that a company does not generate directly, influences potential employees’ inclination to work for, or stay with businesses. In late 2021 a rash of negative headlines about Blue Origin caused difficulties for recruiters, while the opposite was true for SpaceX in July 2020.

‘Earned’ media, which includes all the media activity that a company does not generate directly, influences potential employees’ inclination to work for, or stay with businesses. In late 2021 a rash of negative headlines about Blue Origin caused difficulties for recruiters, while the opposite was true for SpaceX in July 2020.

Even with the appearance and subsequent development of the NewSpace sector, the space sector in general has remained largely unchanged in that it continues to require highly-skilled personnel. The role of an organisation such as HE Space Operations is to provide those resources and for some 40 years, it has been embedding skilled personnel in every major European space programme. The company’s modus operandi is simple: hire the best people and support them to deliver.

As well as providing personnel, the company believes in supporting space professionals as early in the value chain as possible. As such, it is a founding member of Women in Aerospace Europe, regularly supports the Space Generation Council and even has its own children’s foundation enabling less fortunate children to become future space professionals.

Despite the constancy of the need to provide a skilled workforce, the space industry has encountered a number of major disruptions.

Disruption 1: remote working

Despite the constancy of the need to provide a skilled workforce, the space industry has encountered a number of major disruptions

Virtually overnight, the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated existing workplace trends with regard to ways in which professionals were expected to work. Remote working changed from being an occasional tool to employ temporary, outsourced services (usually disconnected from a company’s main establishment) to a non-negotiable demand on employees regarding where they should work.

Employers and employees have had to come to terms with ‘when’ and ‘how much’ work is done in these circumstances, coupled with the experience of ‘death by Zoom’. For example, many parents have juggled a mix of work commitments with the increased demands on their time from family members, while also having to find suitable spaces for working and a stable internet connection.

Remote working limits employee interactions, knowledge sharing and collaboration and can often lead to a feeling of isolation, leading to employee retention issues. This new environment also means that there is no effective way of maintaining a company’s ethos and culture. Nevertheless, being able to cope with the demands and stresses of remote working is now a required part of an employee’s skillset.

From an employer’s point of view, when selecting candidates to fill job descriptions, they can no longer ignore a candidate’s tolerance for remote working as it has a direct influence on ‘boundary control’ - their ability to keep work and family separate, which directly influences when and how much work is done.

As for employee retention, employers will now have to work harder at dynamic reengineering or job redesign. This means figuring out a continually adaptive, proactive and collaborative effort between employees, supervisors and the organisation to find suitable remote working (and eventually hybrid) solutions.

Success in this regard will result in opportunities to change job characteristics, improve organisational efficiency and enhance a ‘person-job fit’. Moreover, for some professionals, remote working resolves the need to relocate and even commute to work, which can enable them to achieve their desired level of boundary control.

Thus, in the medium and long-term, employers will have to come to terms with a percentage of their workforce having no desire to be ‘at work’, again, having to re-engineer the job description to figure out if physical presence in the office is critical at all.

Covid has brought about a shift in the way we work. Employers will now have to work harder at dynamic reengineering or job redesign to find suitable remote working - and eventually hybrid - solutions in order to retain staff.

Covid has brought about a shift in the way we work. Employers will now have to work harder at dynamic reengineering or job redesign to find suitable remote working - and eventually hybrid - solutions in order to retain staff.

Disruption 2: Industry 4.0

The Covid years have shown that the space sector is a very resilient one, but remote working has also highlighted the need for the space sector to re-imagine its current and future operations

The Covid years have shown that the space sector is a very resilient one, but remote working has also highlighted the need for the space sector to reimagine its current and future operations.

Global management consultant McKinsey & Company’s 2020 report, ‘Building the vital skills for the future of work in operations’, states that “The future of work will require two types of changes across the workforce: upskilling, in which staff gain new skills to help in their current roles, and reskilling, in which staff need the capabilities to take on different or entirely new roles.”

Meanwhile, the SmartSat ‘Space Industry Skills Gap Analysis’ report, a detailed and in-depth examination and assessment of Australian space-related skills released in May 2021, identified the following general areas of interest: basic and academic skills; remote sensing/Earth observation; position navigation and timing; engineering; satellite communications; technical skills inferring a mixture of required ‘upskilling’ and ‘reskilling’ to build a space ecosystem.

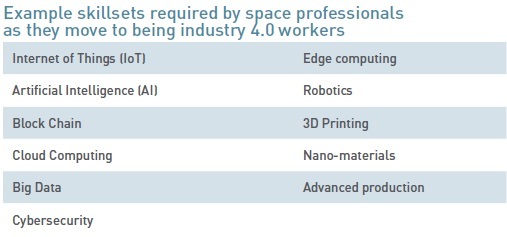

Looking at the requirements for future public space organisations, coupled with the requirements of private space, one sees the heavy influence of Industry 4.0 skillsets and technologies, underpinning the new automation/diversity of technology revolution in the space sector.

These industry 4.0 skills (see table) typically come from the digital world of the Internet and information technology. Given that space professionals are highly skilled, they are increasingly required to upskill in order to be relevant. Indeed, increasing specialism means that in some instances space professionals must either reskill or not actually be employed in the space industry to do tomorrow’s jobs. Interestingly, in some cases, a so-called ‘space professional’ will not have to have any experience of space at all!

The International Commercial Experiment (ICE) Cubes control centre, a public-private partnership with ESA near Munich, Germany. Traditionally a Master’s degree has been a minimum entry requirement for ESA and other space-related organisations but employers could lose out if they continue to ignore a subset of highly skilled people that has not needed to possess an advanced degree.

The International Commercial Experiment (ICE) Cubes control centre, a public-private partnership with ESA near Munich, Germany. Traditionally a Master’s degree has been a minimum entry requirement for ESA and other space-related organisations but employers could lose out if they continue to ignore a subset of highly skilled people that has not needed to possess an advanced degree.

Disruption 3: soft skills

This poses an interesting problem for employers in that, in some instances, a Master’s degree has been seen as the default entry requirement to becoming a space professional. For example, in January 2022, the European Space Agency (ESA) published a schematic where all paths to an ESA staff position originated from an employee having a Master’s degree as a minimum.

However, in the digital and information technology sector, professionals are required to have professional qualifications focused on practical skills (i.e., soft skills) over a university degree (i.e., mental skills). These practical skills are considered ‘soft’ skills, because they are learned, action-based skills where professionals become experts at imitation and recovery of action (i.e., best practice) and increasingly efficient at problem solving. Professionals with MIT’s Professional Certificate Program in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence, Amazon Web Services (AWS) Solutions Architect - Associate etc, are examples of a baseline ‘soft-skill’ requirement for an industry 4.0 workforce.

With this in mind, one could argue that having a Master’s degree should no longer be the minimum level for a space professional. Many have tried to place good candidates with a Bachelor’s degree and over three years of soft-skill experience, but have had limited success, as organisations, especially start-ups, stubbornly fixate on higher degree-based hard skills as a minimum. This is understandable, as cashflow to pay salaries can be constrained in start-up (NewSpace) companies and there is little appetite to take on experienced professionals with enhanced soft skills.

Also, we have seen that some large organisation executive teams are blinded by ‘having a Master’s degree’ and don’t understand, or are unwilling to accept, underlying professional qualifications outside the space sector. As such, employers potentially lose out on advancing their organisational goals and achieving their competitive outcomes, as they totally ignore a subset of highly skilled people that has not needed to possess an advanced degree.

Increasing specialism means that in some instances space professionals must either reskill or not actually be employed in the space industry

But what about traditional soft-skill needs defined by a professional’s emotional ability to collaborate, motivate and empathise with their colleagues? Soft skills literature, including space-focused sources such as the Space Skills Alliance ‘Space Skills Literature Library’ (https://spaceskills.org/library), indicate that much research has been done on the importance of soft skills in the workplace. It is recognised that the lack of soft skills can sink the promising career of someone who has technical ability and professional expertise but no interpersonal qualities. However, looking at the job roles of tomorrow coupled with the disruptions identified earlier, one could argue that this is just an early-career problem.

In the future, given that Industry 4.0 skills will be more needed over a university degree, recognised space-focused professional qualifications which do not yet exist will become increasingly more important.

Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Oxford, UK, works across sectors including Space, Clean Energy, Life Sciences and Quantum Computing, with an increasing number of businesses and start-ups discovering the benefits of collaboration across sectors – space tech that has beneficial Earth applications and vice versa. Recent years have seen an increasingly diverse range of employment opportunities and requirements, which one could characterise as ‘disruptions’.

Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Oxford, UK, works across sectors including Space, Clean Energy, Life Sciences and Quantum Computing, with an increasing number of businesses and start-ups discovering the benefits of collaboration across sectors – space tech that has beneficial Earth applications and vice versa. Recent years have seen an increasingly diverse range of employment opportunities and requirements, which one could characterise as ‘disruptions’.

Disruption 4: company ‘noise’

Even with an increasing tolerance for remote working coupled with the need to develop new types of soft-skills, space professionals are active social agents that need to feel part of an ecosystem and/or social movement. Company media, or ‘noise’, directly communicate organisational reputation and place within an ecosystem.

This seems an odd disruption, but given that the employers furnishing the sector have to make the headlines, the influence of such noise on potential employee motivation and decision-making in applying for a job should not be ignored.

According to a report from SpaceTech Analytics (STA), a strategic analytics agency focused on markets in the Space Exploration, Spaceflight, Space Medicine, and Satellite Tech industries, there are 10,000 SpaceTech related companies, 5000 leading investors, 150 R&D Hubs and Associations, and 130 governmental organisations, each of them with multiple media channels such as corporate websites and social media pages.

Additionally, there is the noise of ‘earned media’ that includes all the media activity that a company does not generate directly, which results from public relations, press mentions and word-of-mouth. Given that this type of noise is not influenced by the 10,000 SpaceTech-related companies, it is seen to be one of the most credible sources for describing a company’s reputation.

In the next 20 years, new definitions of what constitutes a ‘space professional’ might have to be created!

Space professionals are heavily influenced by earned media in decisions related to applying for a job and whether to stay with a company. For example, in October 2021, the Washington Post headlined “Inside Blue Origin: Employees say toxic, dysfunctional ‘bro culture’ led to mistrust, low morale and delays at Jeff Bezos’s space venture”. This was one of many negative publicity headlines for the company that left its recruiters with a difficult recruiting situation. It was in complete contrast to “How SpaceX, social media and the ‘worm’ helped NASA become cool again” headlined by CNBC in July 2020.

Again, looking to the future, company noise, in particular earned media, will continue to differentiate space companies by communicating organisational reputation and place within the ecosystem.

Future definitions

Given the disruptions highlighted, space professionals will continue to ask themselves, “Where do I want to work and why?” and the answers will change as they progress through their careers. Given that the workforce is becoming more Industry 4.0 oriented, non-space derived professionals will be particularly critical of earned media to influence their choice to enter and diversify the sector.

We all accept that companies need people with the right skills to develop, manage and maintain their operational processes. But the definition of what skills are required by space professionals is undergoing disruptive changes driven by the influence of Industry 4.0, whether we like it or not. And this has been catalysed by the pandemic and employer media perception. As a result, in the next 20 years, new definitions of what constitutes a ‘space professional’ might have to be created!

About the author

Jason Maroothynaden is a Business Development Manager and UK Managing Director for HE Space Operations Ltd in Harwell, Oxfordshire. Having studied at Imperial College London and Oxford University, Jason has worked as a bio-instrumentation engineer at ESA/ESTEC and as a business broker in the ESA Space Solutions Programme. With 20 years in the aerospace business and venture capital environment, his expertise covers investment, finance relations, venture growth, downstream applications, microgravity sciences and payload development.