‘Troubled’, ‘once-great’, ‘flagging’, ‘accident-prone’, ‘unreliable’ - these are adjectives often found in western accounts of the present-day Russian space programme. Occasional set-backs quickly attract headlines of ‘another Russian failure’, but are the political prejudices of the new cold war triumphing over reality?

There is no doubt that the Russian space programme contracted greatly from the end of the 1980s, when it operated the Mir space station, launched satellites weekly and roamed the solar system with its unmanned space probes. Shock capitalism in the 1990s reduced space budgets by three quarters, a similar proportion quit the workforce, scientists left for foreign countries and the breakup of the former Soviet states wrecked supply chains. Even electricity became intermittent and spacecraft were completed in darkened hangars by candlelight.

As a result, missions were grounded, delayed and cancelled, while cosmonauts had to remain in orbit until their return spacecraft were ready. Cyclical maintenance stopped, buildings decayed and even fell in on themselves.

By 1997, there were gloomy predictions that the Russian space programme would collapse altogether. The space science side was almost abandoned: lacking data from their own satellites, scientists re-ran ancient datasets or accessed American ones. No more weather satellites were launched and military observation missions became infrequent. Even the libraries could not afford to order journals and President Yeltsin did not seem interested. With no cash, the hidden casualties were new research and development, applications, infrastructure, maintenance, management and quality control.

Dmitry Rogozin (left) on a visit to the Polyot plant.

Dmitry Rogozin (left) on a visit to the Polyot plant.

Recovery

The most state-funded space programme in the world quickly became the most entrepreneurial by making its assets available to other countries

Although the situation appeared to justify the negative headlines, a hidden recovery was in fact already under way. As a result, the most state-funded space programme in the world quickly became the most entrepreneurial by making its assets - launch centres, rockets, spacecraft and space stations – available to other countries…but at a price.

Dmitry Rogozin meeting with Vladimir Putin.

Dmitry Rogozin meeting with Vladimir Putin.

Desperate attempts to bring in cash, such as selling chief designer Sergei Korolev’s slide rule, and even spacecraft sitting on other celestial bodies (‘new owners collect’), were successful. Space tourists paid cash to fly to the International Space Station (ISS). Managers who ran Soviet industries - some of the most efficient in the world - turned their skills to building commercial opportunities with western companies, the most improbable being launching the Soyuz rocket from the European Union territory of French Guiana in the south American jungle. More significantly, Russia’s rocket engines - still the most advanced in the world - were sold to the Americans to power their Antares and Atlas V rockets, the latest batch arriving at the end of 2019. The retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011, and American slowness in making replacement Starliner and Dragon spacecraft flightworthy, meant a ten-year stream of dollars for Russia from delivering astronauts to the ISS.

Moreover, the arrival in the Kremlin of Vladimir Putin made a significant difference. He took a direct interest in the space programme, consulted with industry leaders frequently, personally pinned heroism medals onto cosmonauts and visited design bureaux and factories, which he still tours. A big space science mission planned in the 1980s, the Spektr R telescope, finally flew in 2011 and made a major contribution to astronomy. The space-based navigation system, GLONASS (Russia’s ‘GPS’) was restored to full strength.

There were, however, limits to what could be achieved, as a function of uncertain budget flows. A long-promised return to the Moon with Luna 25, 26, 27 and 28 was repeatedly delayed and these missions have still to fly, while Venera D, a long-duration Venus lander first designed in the 1980s, is not due to appear until the late 2020s.

The retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011 meant a 10-year stream of dollars for Russia from delivering astronauts to the ISS

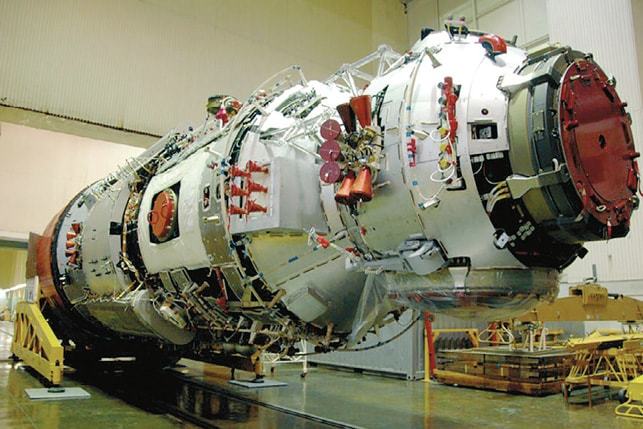

The saddest case was Nauka, the large science module that Russia still wishes to add to the ISS. Built in the 1990s, it is actually the backup to the Functional Control Block (FGB), the first module of the space station. Having languished for years, when eventually prepared for launch it was found that its tanks and pipes had corroded. It went back to the shop for a fix that took years, but it is expected to be shipped to Baikonur for launch in 2021.

One successful strategy was to try to spread costs by involving European countries and the European Space Agency (ESA). Russia launched Europe’s INTEGRAL observatory in exchange for observing time; began the ExoMars project with ESA, which already has an orbiter around Mars; and last summer launched the Spektr RG x-ray observatory carrying German and Russian instruments. And ESA is now on board some of the Luna missions, so they may fly after all.

The Nauka MLM is the backup to the Functional Control Block, the first module on the ISS. This much-delayed unit was originally built in the 1990s and is now planned for delivery to the ISS early in 2021. It will be installed on the Earth-facing docking port of the Zvezda module.

The Nauka MLM is the backup to the Functional Control Block, the first module on the ISS. This much-delayed unit was originally built in the 1990s and is now planned for delivery to the ISS early in 2021. It will be installed on the Earth-facing docking port of the Zvezda module.

Politics

Perhaps the most significant change took place in 2018 with the appointment of Dmitry Rogozin as head of the Russian space agency, Roskosmos. In this case, a space programme hitherto shielded from politics became part of the front line.

Dmitry Rogozin was a parliamentary deputy for the nationalist Rodina (motherland) party, for which he served in the Duma from 1993 to 2007. When Rodina was banned for racism, he left his partisan political past and moved to the political centre, whereupon President Putin appointed him ambassador to NATO in 2008 and then deputy prime minister responsible for space and defence in 2011. After President Putin’s re-election in 2018, he was appointed to head Roskosmos. At first sight, this might appear to be a demotion; however, Rogozin brought a surge of energy to the post and has been seen, ever since, visiting cosmodromes and production plants, welcoming foreign delegations, meeting specialists and encouraging young people into the space programme. He appears to have frequent access to the president.

Then, in the middle of his new governmental career, came the events of 2014 in the Ukraine and Crimea: the US imposed sanctions on 6 March 2014, followed by the European Union on 17 March. This featured a ‘hit list’ of 149 individuals and 38 organisations and was designed to punish nationalist politicians, separatists and oligarchs as well as Russian banks, oil, energy and defence companies, including some in the space industry. The most senior person on the list was Dmitry Rogozin, even though he seems to have had no direct connection to events in these nations. Officially, he was included for supporting the re-incorporation of Crimea into Russia - as did most Russian politicians - but analysts believe that the real purpose was to hit the president’s closest political allies. Being sanctioned, he was prohibited from visiting Europe or the US. Either way, the selection of Rogozin raised serious questions. Given the importance of space cooperation to the US and Europe, was his position on the sanctions list a deliberate attempt to undermine such cooperation? Or did the people who wrote the list even check or consider the consequences?

One successful strategy was to try to spread costs by involving European countries and the European Space Agency

In practical terms, this meant that Rogozin could not attend the Heads of Space Agencies plenary at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Bremen, Germany, in October 2018. Moreover, visa denials to Russian speakers at events in Europe and North America became the norm - something that had never happened during the Cold War from the 1960s to 1980s, nor even in Germany in the 1930s.

Construction of a new Angara pad in Vostochny.

Construction of a new Angara pad in Vostochny.

The sanctions regime had many absurdities. The first ExoMars probe to the red planet, Trace Gas Orbiter, used hydrazine fuel. The Russians traditionally obtained hydrazine from a former Soviet republic, but this was no longer available so it was forced to depend on Europe. The European Union had to amend its own law to permit a breach in its regulations to ship the hydrazine and did so again in 2018 for the second ExoMars probe due to fly 2020. The Russians later opened a new hydrazine factory of their own in Nizhny Novgorod.

Structural issues

In the meantime, the Rogozin-Putin axis got on with the business of rebuilding the Russian space programme. This time, a sustained effort was made to address structural issues, the first of which involved the workforce. Its age profile was the most elderly (and male) of all the world’s space programmes (the exact opposite of China, where the average age is in the 20s). In Russia, young and middle-aged people left in the 1990s and were never replaced; those who stayed took on additional jobs to make a living, a practice that has not yet fully died out. Older people had higher incomes and pensions and had nowhere else to go.

Tsiolkovsky city, Vostochny.

Tsiolkovsky city, Vostochny.

From the arrival of Rogozin, a sustained effort was made to interest young people - boys and girls - in careers in the space industry, with space-related events, training, taster courses and summer camps all around the country; talks were given by cosmonauts and certificates were awarded afterwards. The students were taken to space museums and, in Moscow, the old Cosmos pavilion at the Exhibition of Economic and Scientific Achievements, the VDNK (which had languished ignominiously as a car salesroom in the 1990s), re-opened as a gleaming showcase of Russian space achievement. In keeping with the new media age, Dmitry Rogozin took to Twitter; Roskosmos developed an up-to-date media-friendly website; and the infrastructure agency TsENKI gave NASA a run for its money in live launch broadcasting.

Perhaps the most significant change took place in 2018 with the appointment of Dmitry Rogozin as head of Roskosmos, the Russian space agency

The second issue addressed by the politicians was the problem of the crumbling launch infrastructure. The Russians must have wept whenever they visited China, with its totally modern steel-and-glass buildings while their own launch centres, facilities and offices rotted as the paint peeled away. There had been some renovations in the cosmodromes of Plesetsk and Baikonur in the 1990s, but they were paid for by western companies using these facilities.

Young visitors to VDNK, Moscow.

Young visitors to VDNK, Moscow.

The most spectacular example was the construction of a wholly new cosmodrome in the far east, Vostochny. Launches from the region were not new, for the nearby missile base of Svobodny Blagoveschensk had been used for satellite launches in the 1990s, but this was an entirely new base. The forest was cleared for a Soyuz launch pad, which requires a huge trench and elaborate launch platform and adjacent assembly facilities, while a new town of 30,000 people grew up nearby - named Tsiolkovsky after the father of cosmonautics, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935).

Vostochny saw its first launch in 2016 and five missions have been launched to date. Ultimately, all launches from Baikonur will move there, saving political debts to Kazakhstan from whom it is leased. Perhaps the most ambitious part of renewal is the building of a ‘space city’ in Moscow beside the Khrunichev plant where the Proton rocket has been made. Even at institute level, the biennial meeting of COSPAR – for international space scientists - in 2014 was held in a big, new ‘Fundamental Physics’ building in Moscow.

Thirdly, like the Chinese, the Russians began rolling out a new launcher fleet, replacing existing launchers with a new generation. A new light launcher - the Soyuz 2.1v - was introduced; although it looks like a Soyuz, it uses different engines (NK-33s) and a new upper stage, the Volga (hence the v). It replaces ageing launchers like the Cosmos 3M and missiles built in Ukraine which are no longer available. Soyuz 2.1v has now flown five times.

In addition, the heavy Proton launcher, able to lift over 20 tonnes, will be phased out in favour of the new, more powerful Angara launcher; indeed, it is possible that the last Proton has already been built. The first Angara launch pad was constructed in Plesetsk - more infrastructure renewal - and launched in December 2014. The second Angara pad is, at the time of writing, in construction at Vostochny in the midst of the winter snow.

Another important piece of the jigsaw is a new manned spacecraft to replace the Soyuz, designed in 1960. Called the Orel, its design appears to have been frozen and the newest squad of cosmonauts is already training to fly it. For Orel to reach the Lunar Gateway - the international project to replace the ISS - it will require a new heavy-lift launcher, the design of which Rogozin signed-off in December 2019.

The investment by Putin and Rogozin in a younger workforce, infrastructure, a new launcher fleet and improved quality control are likely to pay dividends well into the 2020s

A fourth and final key area for improvement is quality control. From the 1990s, the Russian space programme began to suffer from increasing instances of quality control lapses, such as the loss of two Mars probes, a constellation of GLONASS satellites and two Progress freighters. Even a Soyuz malfunctioned, the occupants (Alexei Ovchinin and Nick Hague) being saved by the ever-reliable abort system. Quality control problems were a consequence of poor management and morale, the inability to attract and retain the right people, lack of updating of systems, insufficient inspection and the shoddiness of some suppliers - not unique to Russia but creating a vicious circle that was hard to break. Slow but extensive measures were taken to try and squeeze these problems out of the system. The reward came in 2019 when, of 25 Russian launches that year, there was not a single failure.

Russia’s new Soyuz 2.1v light launcher has now flown five times.

Russia’s new Soyuz 2.1v light launcher has now flown five times.

Time will tell if the Putin-Rogozin axis will restore the Russian space programme to its full potential and whether the Russia-Europe-US political standoff will ease. Russia’s recovery has been very much overshadowed by China’s astonishing space achievements. In 2019, China launched 34 rockets, the US 27 and Russia 25. Even if the US abandons the ISS, Russia will not and the Nauka module, when it arrives, will add considerably to the station’s scientific capacity.

Perhaps most importantly, the investment by Putin and Rogozin in a younger workforce, infrastructure, a new launcher fleet and improved quality control are likely to pay dividends well into the 2020s.

About the author

Brian Harvey is a writer on spaceflight based in Dublin, Ireland. His first book was Race into space - the Soviet space programme (Ellis Horwood, 1988), followed by further publications on the Russian, Chinese, European, Indian and Japanese space programmes. His books and book chapters have been translated into Russian, Chinese and Korean. He has just completed China in space - the great leap forward (second, edition, Praxis/Springer, 2019) and is currently writing European-Russian cooperation in space: from de Gaulle to ExoMars, due to be published by Praxis/Springer next year.