The 74th International Astronautical Congress (IAC), held in October 2023 in Baku, Azerbaijan, hosted the usual parallel conference sessions and an exhibition, at which ROOM Space Journal was a media sponsor. Mark Williamson reviews this annual meeting of the global space community and makes some personal observations on the development of the international space industry.

Azerbaijan is not well known for its space industry but it impressed the International Astronautical Federation (IAF) sufficiently to allow it to host the 74th IAC. In fact, it was not the first time that the conference had graced the shores of the Caspian Sea: it was held in the nation’s capital, Baku, in 1973 – exactly half a century ago.

Of course, in those days, any space-related achievements in Azerbaijan were subsumed within the overall Soviet space programme. Indeed, long-term ‘space watchers’ may remember the name of Musa Manarov, the Baku-born Soviet cosmonaut who spent a total of 541 days on the Mir space station.

Today, most of the nation’s space efforts are coordinated by Azercosmos, the Space Agency of the Republic of Azerbaijan, which, via its teleport in Baku, operates the Azerspace-1 and -2 communications satellites and the Azersky imaging satellite. In August 2009, President Ilham Aliyev signed a decree to establish and develop Azerbaijan’s space industry, but these things take time and it can currently best be described as ‘emergent’.

The busy Asgardia and ROOM booth at IAC 2023 during a visit from Head of Nation Dr Igor Ashurbeyli.

The busy Asgardia and ROOM booth at IAC 2023 during a visit from Head of Nation Dr Igor Ashurbeyli.

President Aliyev was an honoured guest at the IAC’s opening ceremony, where he gave a well-crafted political speech detailing what his government had done to improve his country. Given the flaring tensions to the west of the nation that greeted conference-goers a week or so before the IAC began, it was interesting to hear Aliyev’s take on the situation in the disputed territory of Nagorno Karabakh (although the region was not mentioned by name). In keeping with other such IAC ceremonies, the local heritage of astronomical observation and the culture of song and dance provided an antidote to more serious matters.

Parallel universes

China’s presence was significant, with stand space some four or five times that of NASA – and a good deal more interesting

Once the dignitaries are whisked away from the venue, and the security presence fades into the background, the IAC conference and attendant exhibition can settle down to ‘business as usual’. This doesn’t mean that life is any easier, however, as the challenge of choice rears its ugly head. A key problem with events as large as this one is the concept of multiple parallel sessions, which can offer seven or eight technical sessions, along with other events, all happening at the same time. An additional problem in Baku was that technical sessions were spilt between two large buildings, impressive for their architecture but embodying the architectural paradigm of ‘form over function’.

Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku, location for the IAC.

Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku, location for the IAC.

A solution for many of the more technical IAC attendees is that they gravitate towards individual symposia (on space propulsion, space debris or space history, for example), but this tends to result in attendees being ‘siloed’. The fact that the IAC involves content organised separately under the auspices of the International Academy of Astronautics (IAA) and the International Institute of Space Law (IISL) means that, even though the space community prides itself on being ‘cohesive’ and ‘all-inclusive’, engineers rarely talk to lawyers and practicing scientists rarely interact with historians.

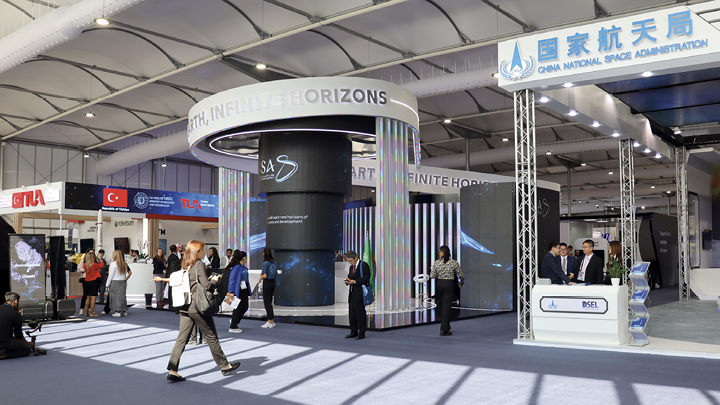

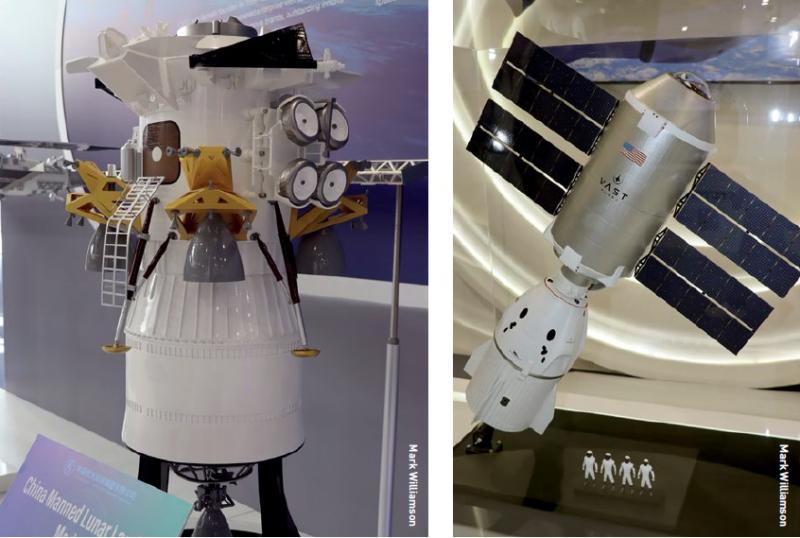

There are, of course, notable exceptions to this notional rule, as witnessed by the forum provided by ROOM magazine, which benefitted from its presence at this year’s exhibition. Although the exhibition was smaller than some, due to the predictable absence of the large American prime contractors, it featured a diverse range of large and small international organisations. China’s presence, for example, was significant, with stand space some four or five times that of NASA – and a good deal more interesting. A 1:15 scale model of the China Space Station took pride of place, while a 1:10 model of a China Manned Lunar Lander (with attached lunar rover) evoked fond memories of Apollo days. Meanwhile, a full-size model of the Yutu-2 lunar rover heralded “Open and Peaceful Utilization” and the promise of the International Lunar Research Station.

Other space agencies in attendance included those of India, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the UK, while companies included AstroScale, i-Space, Surrey Satellite and Thales Alenia Space. It was also interesting to see a new offering from VAST (tagline: “live in space”) in the hall. Having recently emerged from ‘stealth mode’, the company was advertising “Haven-1… scheduled to be the world’s first private space station” (ostensibly from 2025). While it’s always great to see new companies that are ‘keeping the dream alive’, experienced attendees will not be holding their breath for a launch on that timescale.

So, despite the competing attractions of the parallel sessions (and the delights of Baku beyond), the exhibition provided a useful meeting place for a wide variety of participants from across the space community… especially in the late afternoons when the liquid hospitality began to flow. Ultimately, however, it was the free coffee from a local supplier that allowed many of us to navigate the parallel universes of the IAC!

IAC 2023 exhibition entrance.

IAC 2023 exhibition entrance.

Key themes

Despite the push to return to the Moon, there is scant recognition of the issues looming in the cis-lunar environment

It is always interesting - and challenging - to identify the key themes of such an extensive congress. If pressed, one could suggest that they include the ‘top three’ of many of today’s space-related meetings: the renewed focus of lunar exploration; the continuing recognition of the need for space sustainability; and the promise (or threat depending on your national perspective) of China’s advancing space technologies.

Inevitably, the Lunar Gateway system featured broadly among the technical sessions, even though the launch of the first hardware to lunar orbit is at least a couple of years away. Although NASA personnel love to use the strapline “back to stay” in connection with this programme, it is notable that the baseline for the Gateway involves it being crewed for only 30 days a year (over its planned 15-year lifetime). When questioned about this, a speaker responded that this could be extended to 60 days and “even 90 days” (though it was clear that the latter was merely ‘aspirational’). Not entirely unconnected was the revelation (for this author anyway) that the Gateway will not include a toilet (for “water stagnation” reasons); instead, lunar-orbiting astronauts will be required to use the one in the Orion capsule. This design decision was further rationalised by explaining that, in contrast to the International Space Station, Gateway crews will “focus on exploration, not maintenance”. So plumbers need not apply…

More seriously, some of us who can’t wait to get people back to the Moon were somewhat disappointed to hear that the contract for the Gateway airlock has still to be confirmed. This gives the impression that instead of being ‘stuck in Earth orbit’ (as the ISS critique has it), crews will be ‘stuck in lunar orbit’. Apparently, the airlock is not due to be delivered until the Artemis VI mission on a date still unconfirmed.

A 1:10 model of a China manned lunar lander with attached lunar rover and (far right) VAST’s Haven-1 private space station.

A 1:10 model of a China manned lunar lander with attached lunar rover and (far right) VAST’s Haven-1 private space station.

Sustainability

It is good that space sustainability is talked about in conferences such as this, but the community should be wary of over-academising the subject, while its corporations ‘greenwash’ their way to space

In general, there is more positive news on the space sustainability front and this was reflected in a number of conference sessions and exhibits. The need for space debris mitigation in low Earth orbit now seems to be a ‘given’, and there are several systems under development for reorbiting or removing objects and refuelling otherwise healthy satellites. However, despite the push to return to the Moon, there is scant recognition of the issues looming in the cis-lunar environment: with an increase in the lunar orbital population, what about sustainability of that orbit? How much development can the lunar surface environment stand, given its inability to renew itself? The space community is still reluctant to face these issues.

The conference also reinforced the notion that, while many space professionals are well-meaning in their recognition of sustainability issues, the inclusion of the word itself does not necessarily lead to understanding or action. For example, many presenters threw in the acronym SDG (with reference to the United Nations’ 17 sustainable development goals) as if it’s as common as IT, ISS or LEO. One proposal in a ‘sustainability session’ even pitched a “4SDG” structure (covering space economy, security, accessibility and diplomacy) as a basis for potential international agreement. Although it is undeniably beneficial to align ‘space’ with the UN’s goals, it’s debatable whether we need yet more structures and acronyms to do it.

Meanwhile, an IAC plenary on ‘Security, Investment and Sustainability’ – accorded the acronym SIS – provided a good example of how environmental issues can be conflated, and arguably diluted, by association with other, pragmatic near-term issues. It is good that space sustainability is talked about in conferences such as this, but the community should be wary of over-academising the subject, while its corporations ‘greenwash’ their way to space.

All this is not to ignore the Artemis Accords (Principles for a Safe, Peaceful and Prosperous Future), which by November 2023 had been signed by 32 nations, but some question whether this will be enough. A NASA spokesperson stated that there would be “no regulation on the Moon” and that the agency would “rely on the Artemis Accords”. However, one of the world’s leading space nations, China, has yet to sign the Accords… and nor has Russia. If nothing else, this disparity provides material for much legal discussion in the IISL sessions of the IAC.

Idiosyncrasies

For all its idiosyncrasies, the International Astronautical Congress remains, arguably, the world’s most diverse and multidisciplinary space conference

In fact, it was in one of these law sessions that ROOM magazine’s founder and benefactor, Igor Ashurbeyli, received some unwanted publicity. One typically outspoken law professor included a Photoshopped representation of the Head of Asgardia, the Space Nation, wearing a jewelled crown, declaring the concept of Asgardia “stupid”. With reference to Asgardia’s goal of facilitating the birth of the first child in space, he also revealed, without specifics, that “a Dutch organisation” was already investigating “the ethics of babies in space”. In fact, Asgardia has already been associated with Netherlands-based SpaceBorn United whose CEO Egbert Edelbroek was an MP in the Asgardia Parliament.

Although the audience failed to challenge the speaker on his views, several attendees considered his characterisations to be unprofessional, especially under the auspices of such a well-regarded congress. No-one can say whether Asgardia will outlive its 10th anniversary in October 2026 – like so many things it will depend on sufficient funding – but Ashurbeyli could still have the last laugh.

For all its idiosyncrasies, the International Astronautical Congress remains, arguably, the world’s most diverse and multidisciplinary space conference and, for many, is their annual ‘must attend event’. Indeed, some of us IAC aficionados can count IAC attendances into the dozens!

These events are so involved and expensive to organise that their locations are decided up to three years in advance. Thus, next year’s congress will be held in Milan, Italy, with the 2025 and 2026 events planned, respectively, for Sydney, Australia and Antalya, Turkey. I think I’d better invest in a new suitcase!

Asgardia’s head of national Dr Igor Ashurbeyli with space nation ministers, MPs and support staff at IAC 2023 in Baku.

Asgardia’s head of national Dr Igor Ashurbeyli with space nation ministers, MPs and support staff at IAC 2023 in Baku.

About the author

Mark Williamson is an independent Space Technology Consultant to the space industry, space insurance and space education sectors. As a chartered physicist and chartered engineer, he has 40 years’ experience in satellite communications engineering and consultancy. He is also the author of six books (including The Cambridge Dictionary of Space Technology and Space: The Fragile Frontier), has edited three space industry magazines and written more than 600 articles and papers on space technology. He has a BSc in physics and astrophysics from Queen Mary London and a PhD in sustainable development of the space environment from the University of Sunderland. He is a Commissioning Editor for ROOM Space Journal.