The topic raised by Keen at November’s TEDxESA ‘Science Beyond Fiction’ is a complex one. In her signature humorous style, Keen provides multiple examples of forgotten corners of space exploration history, mixing them with a discussion of the social aspects of women in space exploration.

She brings forth the idea that not only can avenues of space research be severely limited by social stereotyping but many of those scientific discoveries that do fall outside the widely accepted norm are at best soon forgotten by the public and, at worst, never known to begin with.

But let’s look at it from the beginning. As Keen mentions, the USA did not have a woman in space until 1983. The Soviet Union, on the other hand, sent the first woman into space back in 1963 (Valentina Tereshkova, 16 June 1963, on Vostok-6). Tereshkova remains the only woman to have gone to space solo.

For 20 years, social factors in the US and the very attitude that there was really no point in sending a female astronaut to begin with, halted progress in that regard completely. And yet, Tereshkova’s story isn’t quite as simple as being a milestone for women’s rights and progress. Little known facts are that she remained practically immobile for the duration of her flight and didn’t eat during her three days in space.

Surviving members of the original Mercury 13 on a Kennedy Space Center visit to witness a Space Shuttle launch - though they were not given the chance to become astronauts and the United States would not launch a woman into space until 1983, these women proved women were physically and mentally qualified for space travel.

Surviving members of the original Mercury 13 on a Kennedy Space Center visit to witness a Space Shuttle launch - though they were not given the chance to become astronauts and the United States would not launch a woman into space until 1983, these women proved women were physically and mentally qualified for space travel.

Upon her successful return to Earth, Sergey Kovalev (lead Soviet rocket engineer during the Space Race years) is rumoured to have exclaimed that another woman would only be sent to space over his dead body. And as it turned out, the USSR did not send another female astronaut into space until 1982 when Svetlana Savitzskaya became the first woman to make a spacewalk.

All in all, the early years of women in space had much less to do with women’s rights than with grabbing the lead and reaching another milestone in the Space Race. Looking back, it is perhaps somewhat ironic that the USSR succeeded in beating the US in this aspect of space exploration - while the US didn’t think this was an aspect worthy of exploration and competition to begin with.

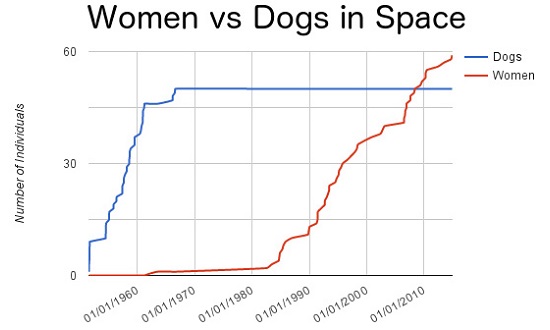

Unfortunately for budding female astronauts of the 1960s, no one cared much about their rights or personal accomplishments but rather used them much like they used various animals sent into space - a new animal is a new milestone, nothing more. As Keen mentioned, the number of women and dogs in space only evened out about seven years ago (when counting individual instances of dogs and women sent to space, as some have been in space more than once).

Research was limited by an imagination that did not see the point of women in space

And yet, women were vital to space research before the 1980s. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory was unusual for the time - it began employing female mathematicians as early as the 1940s. These women performed detailed trajectory calculations, yet their importance in space history is virtually unknown by the wider public. Dana Ulery, the first female engineer at NASA (hired in 1961) is not a household name by anyone’s standard, yet she automated real-time tracking systems for Ranger and Mariner space missions! Of course, 1952 also saw the start of the ‘Miss Guided Missile’ beauty pageant which was renamed ‘Queen of Outer Space’ in 1959.

Public knowledge omissions such as the above are precisely what Keen talked about. First, research was limited by an imagination that did not see the point of women in space. Then, wearing tiaras and competing in pageants, they quietly entered the industry - an industry that used their talents but hardly acknowledged their existence publicly for many years.

Finally, in 1960, William Randolph Lovelace II, who had helped develop tests for NASA’s male astronauts, let his imagination soar and asked himself - how would women perform on these tests? It was a question that hadn’t occurred to anyone and was met with a fair amount of scepticism from his colleagues, who did not see the point of testing women no one was planning to send into space anyway.

Geraldyn ‘Jerrie’ Cobb, one of the original Mercury 13

Geraldyn ‘Jerrie’ Cobb, one of the original Mercury 13

Lovelace argued that women may actually make better candidates than men - they typically weigh less, breathe less oxygen and even produce less waste. And so he invited Geraldyn ‘Jerrie’ Cobb to undergo the same testing as the men. She became one of the Mercury 13 - thirteen American women who underwent the same testing that Project Mercury astronauts had. They were never officially part of NASA’s astronaut programme and none of them made it to space. The testing was privately financed by aviator Jacqueline Cochran.

Cobb, like the other candidates, was already an accomplished pilot. Now working with Lovelace, she looked through the records of over 700 female pilots and ended up recruiting 19 other women. All of them had at least 1000 hours of flight experience.

Lovelace argued that women may actually make better candidates than men - they typically weigh less, breathe less oxygen and even produce less waste

Twelve women in addition to Cobb were finally chosen to undergo testing after the rest were disqualified for medical reasons. Cobb called them the Fellow Lady Astronaut Trainees (FLATs for short) and later they became known as the Mercury 13 - Myrtle Cagle, Jerrie Cobb, Janet Dietrich, Marion Dietrich, Wally Funk, Sarah Gorelick, Janey Hart, Jean Hixson, Rhea Hurrle, Gene Nora Stumbough, Irene Leverton, Jerri Sloan, Bernice Steadman.

Since very little was known about what awaited astronauts in space, the tests ranged from x-ray to electric shock and ice water in the ear to induce vertigo. All of the Mercury 13 passed the initial phase of testing.

For various reasons, including family obligations, only three of the women - Jerrie Cobb, Rhea Hurrle and Wally Funk - went on to Phase II testing which involved isolation tank and psychological tests. Cobb was the first one to move on to and pass Phase III testing (aeromedical, using military equipment and jets). The other two women were prepared to go through Phase III testing as well but, without an official request from NASA, the Naval School of Aviation Medicine did not give its consent for the tests.

In the end, Cobb was the only one out of the group to complete full testing. Cobb and Hart lobbied for the programme but were met with a dire lack of imagination, drawing astronaut John Glenn to comment: “The fact that women are not in this field is a fact of our social order.”

In the end, no decisive action was taken to promote female astronaut training. The Mercury 13 came into under spotlight again in 1963 after Tereshkova’s flight. The names of all 13 women were made public for the first time in LIFE magazine but soon after, as the US continued to have no interest in a female astronaut programme they faded from public view and the Mercury 13 became a story obscured by lack of imagination.

In the greater historical context of the social framework limiting the imagination and curiosity of scientists and eventually leading to selective obscurity of important historical feats the Mercury 13 are not an exception.

Katherine Johnson was the human computer who’d calculated the Apollo 11 trajectory to the Moon - the trajectory that ultimately led to humanity’s first steps on a celestial body other than Earth. Eileen Collins became the first female to pilot the Space Shuttle. Ed Dwight - the first African-American -astronaut trainee (selected by the Kennedy administration despite open discrimination - continued to train as an astronaut until Kennedy’s assassination made it impossible for him to continue his work and resigned from the Air Force in 1966.

Middle right: Joan Higginbotham was elected as an astronaut candidate by NASA in April 1996 and flew as a mission specialist on STS-116 Space Shuttle Discovery in December 2006

Middle right: Joan Higginbotham was elected as an astronaut candidate by NASA in April 1996 and flew as a mission specialist on STS-116 Space Shuttle Discovery in December 2006

Margaret Hamilton, who developed flight software for the Apollo space programme (work that eventually prevented an abort of the first Moon landing almost triggered by the computer) is also credited with coining the term ‘software engineering’. Only in 2013 did NASA finally hire an equal number of men and women (four of each) for its 2013 astronaut class.

These trailblazers discussed by Helen Keen in her presentation at TEDxESA are only a few of the many people whose ability to contribute to scientific advances was stunted by the lack of imagination around them.

Veterok and Ugolyok, launched into space on 22 February 1966 aboard the Cosmos-110 biosatellite, pictured at the Institute of Medical and Biological Problems, USSR Ministry of Health

Veterok and Ugolyok, launched into space on 22 February 1966 aboard the Cosmos-110 biosatellite, pictured at the Institute of Medical and Biological Problems, USSR Ministry of Health

As she says: “I always think there are so many stories that we haven’t heard! And so many stories even from the 1960s that we still haven’t heard! I only found out recently that in the 1950s and 60s in Langley, Virginia, there were a group of female mathematicians - African-American mathematicians - who were working on calculating trajectories for the Apollo missions. They were living in a racially segregated society and calculating where spacecraft were going to travel beyond Earth’s atmosphere. That’s just such a wonderful story!”

This story, and the other wonderful stories she mentions, all add up to one idea - the idea that limiting ourselves, for whatever reason only limits our ability to advance faster, better and further.

Valentina Tereshkova

Valentina Tereshkova

Keen ended her presentation with a quote from one of her favourite astronauts, the first African-American woman in space, Dr Mae Jemison, ‘Never be limited by other people’s limited imaginations’.

For scientists, for researchers, for all those striving to break out of limited contentment and go beyond the already discovered - to all those, Keen would say that these are, indeed, words to live by.