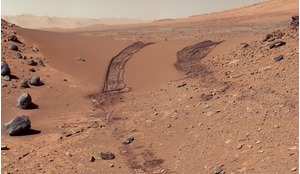

Researchers studying the psychology of space travel have long been interested in the phases of change that could occur in human performance and health during prolonged missions beyond Earth’s orbit. If patterns of mood change and performance during spaceflight could be reliably predicted, mission planners could introduce additional training and countermeasures aimed at optimising crew health and cohesion during critical phases. Nathan Smith and Gro Sandal examine the evidence for what has become known as the ‘third quarter phenomenon’ and consider its implications for space travel.

Over 30 years ago, a review of groups in extreme environments (Harrison and Connors, 1984) suggested that mood and morale would reach a low point at some stage beyond the halfway mark of different missions. Taking this idea further, Robert Bechtel and Amy Berning (1991) were the first to coin the term the ‘third quarter phenomenon’ (TQP). Their study, largely based on anecdotal evidence and reflections from the cold regions study project, proposed that those undertaking deployments in challenging scenarios are likely to experience a reduction in mood, irritability, tension and decreased morale after the midpoint and into the third phase of a mission – the TQP. Further, their review suggested that this was more a relative than absolute phenomenon that occurred regardless of the overall length of a mission.

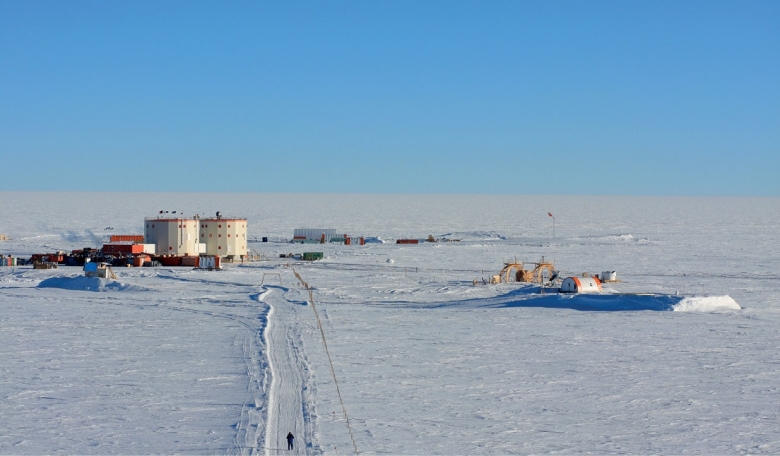

Early evidence for the relative nature of the TQP was provided by Connors et al. (1985) looking at the results of those undertaking a year-long stay in Antarctica, a short submarine mission, and inpiduals participating in a 90-day simulation study. What counts, psychologically, seems to be the knowledge that the first half of the stay is finished, and the anticipation that an equally long period of time lies ahead.

Find out more about the third quarter phenomenon and how long-term space travel can affect the human mind in the full version of the article, available now to our subscribers.