The study of exoplanets has rarely left the news since their first discovery two decades ago [1] - and the headlines are unlikely to stop anytime soon. With a variety of future-planned space programmes in development to find even more systems, the number of detected planets will increase three-fold, if not more. But aside from knowing that exoplanets are ubiquitous and can be found around all types of stars, what else do we really know about them? Very little as it turns out. Not content with merely counting other worlds, scientists at UCL are developing a mission to study the atmospheres of at least 100 bright exoplanets in the Milky Way in a bid to add substance to planet style.

Since the discovery of 51 Pegasi b (also known as Dimidium) just over 20 years ago, the list of planets discovered orbiting distant stars has reached well over 3000. Ongoing and planned ESA and NASA space missions such as GAIA, Cheops, PLATO, Kepler II and TESS will increase the number of known systems to tens of thousands. Exoplanets have been detected around every type of star and our current statistical estimates suggest that, on average, every star has at least one planetary companion. That means that there are hundreds of billions of planets in the Milky Way alone.

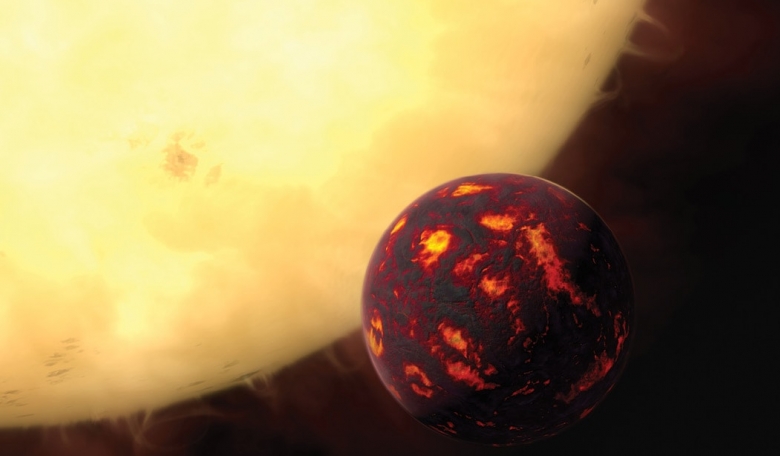

To the gas giants, rocky terrestrial planets and ice-worlds that we find in our own solar system, we have added a broad spectrum of new, exotic planetary types: giant hot-Jupiters orbiting their sun in hours or a handful of days, super-Earths with masses up to ten times that of our planet, gas dwarfs, temperate Neptunes. The sheer range of planetary bodies discovered has caused a paradigm shift in how we think about planetary systems and our understanding of how they form and evolve.

But in reality, what do we know about the individual planets? The answer is very little. For most, we simply know that they exist and where they are. For about a third of them, we know how big they are, their mass and how often they orbit their star. For about one per cent, we have used spectroscopy to extract a few clues about their atmospheric temperature and composition.

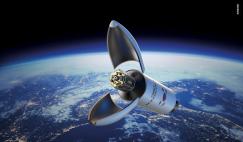

Twinkle is a small, low-cost mission that will study the atmospheres of at least 100 bright exoplanets in the Milky Way using optical and infrared spectroscopy. The targets observed by Twinkle will comprise known exoplanets discovered by existing and upcoming ground surveys in our galaxy (e.g. WASP or HATNet) and space observatories (Kepler-2, GAIA, Cheops and TESS). The Twinkle satellite will be built in the UK and launched into a low-Earth, sun-synchronous orbit by 2019, using a platform designed by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd and a payload built by a consortium of UK institutes led by UCL.

Read more about the exciting discoveries that await the Twinkle mission, as well as its capabilities and goals in the full version of the article, available now to our subscribers.