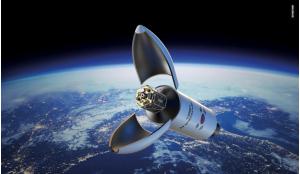

Every day Earth observation satellites generate vast amounts of data helping us to manage our resources, monitor and protect our environment and respond to humanitarian disasters. But getting this data back to Earth is a huge challenge. Radio frequency (RF) technology has hardly changed since the days of Sputnik and no matter how many terabytes of data sensors can collect, RF limits the flow of data to the ground to a trickle. To get the most out of Earth observation satellites, we need a high-speed data connection in space just as much as we do on the ground.

Last September NASA once again delayed the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), pushing it three years past its initial launch date to 2021. James Webb will peer into the cosmos using the most advanced imaging hardware available. The telescope’s mirror, a colossal honeycomb of gold-plated beryllium, is three times larger than the mirror on the Hubble telescope it replaces. Costing over US$9 billion, James Webb is the size of a yacht and has been under development since 1996. In the same time frame, thousands of small satellites will have gone into orbit, each no bigger than a suitcase and costing no more than a few million dollars.

While JWST probes into the deepest reaches of the universe, most of these small satellites will be looking back at our own planet. These satellites make up the rapidly expanding Earth observation industry, on a mission to understand the planet we live on like never before.