Jupiter’s icy moon Europa has long intrigued scientists with its potential to harbour a subsurface ocean beneath its frozen crust. As Project Scientist for NASA’s Europa Clipper mission and a planetary scientist at Brown University, Dr Ingrid Daubar is at the forefront of efforts to explore this enigmatic world. In this article, she shares insights into the mission’s objectives, the challenges of deep space exploration, and the quest to determine whether Europa could support life.

Astrobiology studies the origin, evolution, distribution and future of life in the universe. We know that Earth is teeming with life but determining whether life exists elsewhere in the universe is hugely challenging. Astronomers use ground-based and space-based telescopes to find and study exoplanets but with current spaceflight technology it would take thousands of years to reach even the nearest stars. For now, the best thing we can do to see if there is life beyond Earth, is to explore closer to home.

The three main conditions required for life on Earth are: liquid water, a source of energy, and the presence of the right chemical elements, and Jupiter’s moon Europa seems to meet all of these conditions.

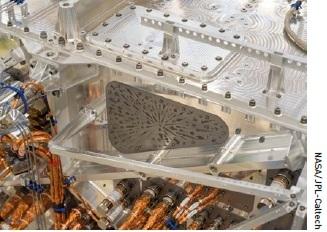

Europa Clipper’s Vault Plate is made of tantalum metal about 1 mm thick, 7 inches (18 cm) tall and 11 inches (28 cm) wide. It is part of the structure that will protect Europa Clipper’s electronics from Jupiter’s harmful radiation. The outward-facing side of the vault plate is engraved with waveforms for the word “water” in 104 languages. The waveforms extend from a circular symbol in the middle of the design, which represents the non-spoken word for water in American Sign Language.

Europa Clipper’s Vault Plate is made of tantalum metal about 1 mm thick, 7 inches (18 cm) tall and 11 inches (28 cm) wide. It is part of the structure that will protect Europa Clipper’s electronics from Jupiter’s harmful radiation. The outward-facing side of the vault plate is engraved with waveforms for the word “water” in 104 languages. The waveforms extend from a circular symbol in the middle of the design, which represents the non-spoken word for water in American Sign Language.

Evidence for an ocean

Decades of data from previous missions like Galileo, the first mission to measure Jupiter’s atmosphere directly with a descent probe, along with Earth-based observations, provide compelling evidence that a global ocean lies beneath Europa’s ice. The Galileo spacecraft orbited Jupiter for almost eight years and magnetometer readings revealed magnetic field fluctuations consistent with a conductive layer - likely a salty liquid ocean. Observations of chaotic terrain and surface features suggest material from beneath the ice may be rising to the surface. These findings, along with recent telescope studies that hint at water vapour plumes, have strengthened the case for an active ocean world.

Scientists believe that elements including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulphur - the building blocks of life - were likely incorporated into Europa as it formed. Later, asteroids and comets collided with the moon and may have left more organic materials.

To protect the Europa Clipper from intense radiation levels the spacecraft will orbit Jupiter and carry out flybys of Europa.

To protect the Europa Clipper from intense radiation levels the spacecraft will orbit Jupiter and carry out flybys of Europa.

Europa’s main energy source is tidal heating, caused by its elliptical orbit around Jupiter. The gravitational tug of Jupiter causes ‘tidal flexing’ where the moon is stretched and compressed, generating heat internally.

Jupiter’s icy moon Europa has long intrigued scientists with its potential to harbour a subsurface ocean beneath its frozen crust

Europa presents a unique landscape in our solar system. Unlike many planetary bodies, it has relatively few impact craters, suggesting a young and dynamic surface. This scarcity of craters indicates active geological processes that may be resurfacing the moon and erasing older features. The few craters that do exist are particularly intriguing, as their distinct appearances hint that the subsurface ocean is influencing surface geology.

Recent studies suggest that Europa’s surface is shaped by tectonic-like processes, driven by the tidal flexing from Jupiter’s gravitational pull. This constant ‘kneading’ of the moon’s interior not only keeps its ocean in a liquid state but also causes the icy crust to fracture and shift. These movements could enable nutrients and energy to cycle between the surface and the ocean, a key factor in determining the moon’s habitability.

The primary goal of the Europa Clipper mission is to assess the moon’s potential habitability. To achieve this, the spacecraft will conduct dozens of close flybys, each one covering a different area so that almost the entire moon is scanned. It will carry out detailed reconnaissance of Europa’s surface and subsurface, investigating the thickness of the ice shell, the depth and salinity of the ocean beneath, and the extent of material exchange between the ocean and the surface. Understanding these factors is crucial in determining whether Europa possesses the necessary conditions to support life.

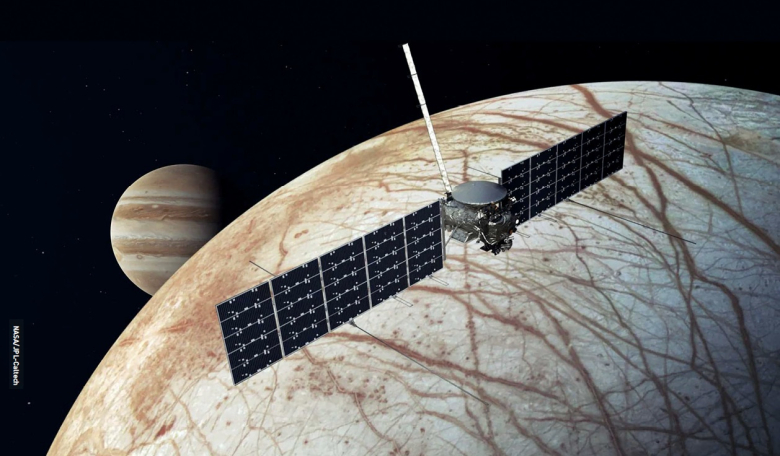

Illustration of NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft above the surface of Europa and in front of Jupiter.

Illustration of NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft above the surface of Europa and in front of Jupiter.

Instruments and techniques

Europa Clipper is the largest spacecraft NASA has ever built for a planetary mission, spanning more than 100 feet (about 30 m) with its solar arrays deployed. It is equipped with a suite of sophisticated instruments designed to probe the moon’s secrets:

- REASON (Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding - ocean to near-surface): This ice-penetrating radar will map the structure of Europa’s ice shell and detect any subsurface water bodies.

- EIS (Europa Imaging System): A wide-angle camera and a narrow-angle camera will study geologic activity, measure surface elevations, and provide context for other instruments.

- E-THEMIS (Europa Thermal Emission Imaging System): A thermal camera that will identify areas of recent or ongoing geological activity by detecting subtle thermal anomalies.

- Europa-UVS (Europa Ultraviolet Spectrograph): This spectrograph will study the composition and structure of Europa’s atmosphere and any plumes.

- MISE (Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa): For mapping the distribution of ices, salts, organics, and the warmest hotspots on Europa.

- ECM (Europa Clipper Magnetometer): This instrument will measure strength and orientation of magnetic fields. It should allow scientists to confirm that Europa’s ocean exists, measure its depth and salinity, and measure the moon’s ice shell thickness.

- PIMS (Plasma Instrument for Magnetic Sounding): PIMS Faraday cups will distinguish distortions from Europa’s ionosphere and plasma trapped in Jupiter’s magnetic field from Europa’s induced magnetic field, which carries information about Europa’s ocean.

- Gravity/Radio Science instrument: Measuring Europa’s gravity at various points in the moon’s orbit will show how Europa flexes and help reveal its internal structure

- MASPEX (Mass Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration) and SUDA (Surface Dust Analyzer): These instruments will analyse the composition of particles in Europa’s thin atmosphere and any potential plumes, searching for organic molecules.

By integrating data from these instruments, the mission aims to build a comprehensive picture of Europa’s habitability.

The mission’s science goals are guided by three overarching themes: to confirm the presence and characteristics of the subsurface ocean, to explore the composition of the surface and subsurface, and to study the geology to understand current and past activity. These objectives are aligned with NASA’s broader search for biosignatures and environments where life as we know it could exist.

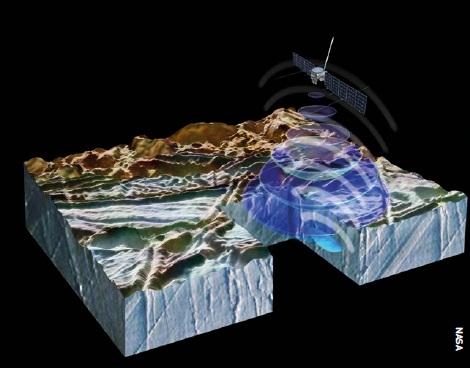

The ice-penetrating radar of REASON - Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface – one of nine instruments aboard Europa Clipper, will peer beneath the moon’s icy crust to reveal the structure beneath.

The ice-penetrating radar of REASON - Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface – one of nine instruments aboard Europa Clipper, will peer beneath the moon’s icy crust to reveal the structure beneath.

Challenges of deep space exploration

The Europa Clipper mission represents a significant step forward in our quest to understand the potential for life beyond Earth

Operating in the harsh environment of the Jupiter system presents significant challenges. Europa Clipper must withstand intense radiation levels, necessitating robust shielding and radiation-hardened electronics. Its payload and other electronics will be enclosed in a thick-walled vault made of titanium and aluminium to slow down degradation by high-energy atomic particles. Additionally, the spacecraft’s instruments must function flawlessly after a journey of over 1.8 billion miles (taking around five and a half years from launch to arrival at Jupiter), requiring meticulous testing and calibration.

Because of the distance and communication delay, Europa Clipper must operate with a degree of autonomy. The spacecraft uses advanced onboard systems that allow it to make some navigation and data collection decisions independently. These autonomous systems help it react to changing conditions during each close flyby of Europa, ensuring that critical science operations are carried out even with limited contact with mission control.

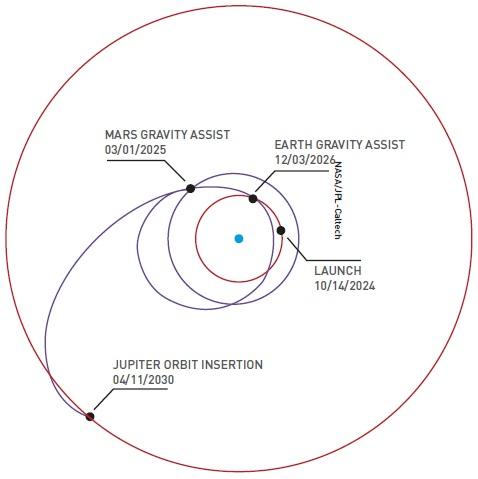

To optimise its trajectory, Europa Clipper performed a gravity assist manoeuvre by flying just 550 miles above Mars on 1 March 2025. The flyby not only adjusted the spacecraft’s path but also provided an opportunity to test instruments like E-THEMIS, which captured over a thousand infrared images of Mars during the encounter. This, and a second flyby in 2026, this time of Earth, will give the spacecraft the energy it needs to reach Jupiter.

International collaboration

The quest to explore Europa is a global endeavour. NASA’s Europa Clipper mission complements the European Space Agency’s JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) mission, which will also study Europa, along with the two other large ocean-bearing Jovian moons, Ganymede and Callisto. The two missions have coordinated efforts, with instruments like Clipper’s REASON and JUICE’s RIME (Radar for Icy Moon Exploration) designed to provide complementary data sets.

Europa Clipper’s reconnaissance will lay the groundwork for potential future missions, including landers that could directly sample the surface or even penetrate the ice to access the ocean below. By identifying regions of interest, such as areas with recent geological activity or potential plume sources, Clipper will help determine the most promising sites for in-depth exploration.

The Europa Clipper mission represents a significant step forward in our quest to understand the potential for life beyond Earth. By investigating Europa’s subsurface ocean, ice shell and surface composition, we aim to uncover the secrets of this intriguing moon and assess its habitability. The insights gained will not only enhance our knowledge of Europa but also inform our understanding of other ocean worlds in our solar system and beyond.

Artist’s concept depicting NASA’s Europa Clipper as it flies by Mars, using the planet’s gravitational pull to alter the spacecraft’s path on its way to the Jupiter system.

Artist’s concept depicting NASA’s Europa Clipper as it flies by Mars, using the planet’s gravitational pull to alter the spacecraft’s path on its way to the Jupiter system.

Editor’s Note

This article is based on an interview conducted by Steve Kelly at the Northeast Astronomy Forum (NEAF) in New York in the spring of 2025.

About the author

Dr Ingrid Daubar is a planetary scientist at Brown University and a Project Scientist for NASA with extensive experience in scientific research and space mission operations. Her research interests focus on impact cratering and time-varying phenomena on planetary surfaces. Dr Daubar has participated in science and operations on multiple NASA planetary missions and instruments including HiRISE (High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment), InSight (Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport), Europa Clipper, and Juno.