On the BBC six o’clock news of 15 July 2015, as a result of the first New Horizons images, several paintings of Pluto were shown (some by myself) with the statement, ‘There is no longer any need for artists’ impressions.’ This comment was of course intended to be whimsical but, as the public sees it, there is an element of truth in it. We have after all now received images from all of the major bodies in our Solar System.

There will always be a need for artists (quite apart from the aesthetic aspects; space art can be at least as beautiful as terrestrial art) because from space probes we only see the whole object – planet, moon, comet - or close-ups of it, as it looks from space. Only artists can visualise what it would look like for someone actually standing on the surface. Of course, we heard the same sort of comments when photography was invented, when digital art became available, when the Hubble Space Telescope sent back its first amazing images of distant stars and nebulae. . . But let’s take a look at the history and background of space art.

Most space artists would dearly love to visit other worlds; even to take a trip into Earth orbit

Astronomical artists are sometimes divided into First and Second Generation (and I suppose that now we have even more). The first group were pioneers; they were the first in their field and had nothing to work with but their own knowledge, observations, intuition and talent. They include James Nasmyth, who in 1874 made models of the Moon’s surface and photographed them against a black, starry background for his book with James Carpenter, The Moon. Scriven Bolton later used a similar technique for The Illustrated London News. By far the most accurate artist was French astronomer Lucien Rudaux who, because he was an observer and had an observatory in Donville, Normandy, knew what the lunar mountains really look like in profile. His 1937 book Sur les Autres Mondes (On Other Worlds) is a classic.

Master of space art

The best-known space artist from the forties and fifties was the American Chesley Bonestell. It has come to light only relatively recently, thanks to artist and curator of the Bonestell estate Ron Miller, that Bonestell too made models, photographed them and painted over them in oils, creating amazingly realistic scenes of the Moon and planets. But his work became known for its jagged, craggy lunar landscapes, a result of his belief that without air, water or weather the mountains would be as rugged as the day they were born. He did not take into account the aeons of impacts by micrometeorites or the extremes of temperature, leading to the gradual flaking of rocks, which produced the rolling landscapes revealed by the Apollo landings in the 1960s. Even so, his influence cannot be overestimated.

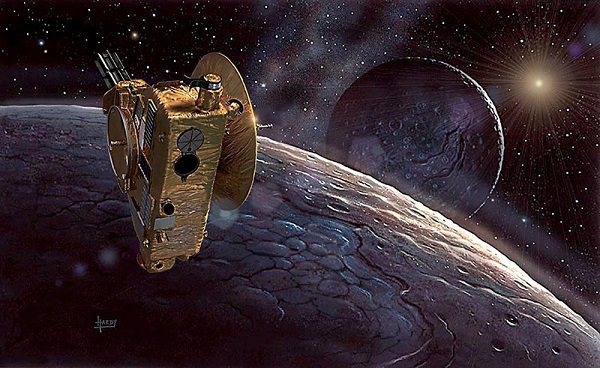

A painting of Pluto & Charon done in 1991, plus a 3D model of New Horizons by Dan Durda added in 2015. Note the atmospheric haze, the similarity to Sputnik Planum, and the chasms on Charon! (Gouache + digital)

A painting of Pluto & Charon done in 1991, plus a 3D model of New Horizons by Dan Durda added in 2015. Note the atmospheric haze, the similarity to Sputnik Planum, and the chasms on Charon! (Gouache + digital)

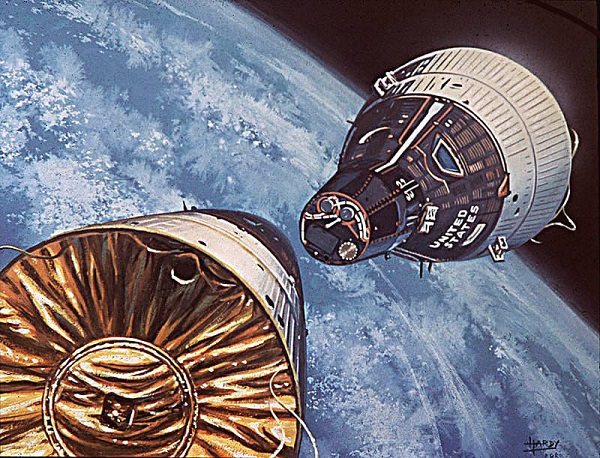

Gemini 6 and 7 docking in December 1965. There was nobody to photograph this historic event so it’s up to the artist! (Gouache, painted in 1970 for a VP filmstrip with Len Carter)

Gemini 6 and 7 docking in December 1965. There was nobody to photograph this historic event so it’s up to the artist! (Gouache, painted in 1970 for a VP filmstrip with Len Carter)

Chesley Bonestell was born in 1888. The Wright Brothers were then 17 and 21, and HG Wells was 22 and not yet published. Yet Bonestell was able to see his visions of men walking on the Moon and probes visiting most of the major planets become reality, for he died in 1986.

Artists have the advantage of being able to travel in time as well as space

Bonestell’s first published astronomical art was a series of paintings of Saturn from its (then nine) moons for a 1944 issue of Life magazine. Arthur C. Clarke was outraged by the comment of a shortsighted editor that ‘the figures (of astronauts) are included only to give scale’! Bonestell worked on special effects for films under producer George Pal, including Destination Moon and Conquest of Space. He went on to lead a team of illustrators, working with scientist-writers under Wernher von Braun and Willy Ley, on a series of articles for Collier’s magazine, showing how humans could explore space, from a wheel-shaped station in orbit to a fleet of moonships, and later a mission to Mars.

There can be no doubt that they succeeded spectacularly in showing a US public, whose lives had been dominated by Korea and the Cold War, a vision of a new frontier and great glory. In fact, they created a climate in which NASA could begin its work. Von Braun later designed the rocket motors which launched America’s first artificial satellite, and the Saturn V which took Apollo astronauts to the Moon.

But Bonestell’s highly realistic, even photographic oil paintings had another effect. As we have seen, his moonscapes showed dramatic, towering mountains - so much more inspiring than the flat, drab landscape on which Apollo 11 landed! Could the disappointment of this reality have been a factor in the public’s rapid disenchantment with the space programme?

Space hotel with zero-g stadium and super-shuttles (Gouache + digital). From ‘Futures: 50 Years in Space’ by David A Hardy & Patrick Moore, 2004

Space hotel with zero-g stadium and super-shuttles (Gouache + digital). From ‘Futures: 50 Years in Space’ by David A Hardy & Patrick Moore, 2004

Throughout the 1950s, science fiction and other illustrators who had never even looked through a telescope produced variations of Bonestell’s Moon (a warning to us all to do our own research and not copy the work of others). Even so, the books which followed the Life and Collier’s articles - Conquest of Space (1949), Across the Space Frontier (1952) and Man on the Moon (1953), among others, inspired future generations of space artists, including of course myself.

Early space artists

In 1950s Britain there was RA (Ralph) Smith, who worked with Arthur C Clarke and the British Interplanetary Society. Smith was an engineer as well as an artist, so was able to design his own vehicles and hardware, which he did to great effect: ‘ferry rockets’, forerunners of the Space Shuttle, a space station powered by solar energy, Moon bases and much more. The Czech artist Ludek Pesek is often cited as one of these pioneers but in fact his work was not seen until the 1960s and he came to prominence in 1970 for his excellent paintings of Mars in the National Geographic. However, his rather loose, painterly style was in great contrast to Bonestell’s tight, photographic technique. One could imagine that he had sat there with his easel, painting en plein aire. Or, in the case of the Moon, en plein espace!

At first these artists could only use for reference what they could see through telescopes, or the results from major observatories such as those at Mt Wilson and Mt Palomar. I consider myself fortunate - I might even use the overworked word ‘privileged’ - because my own career overlapped the last two, starting as I did around 1950. A few years later saw the dawn of the Space Age, with the launch of Sputnik 1, and we began to see the work of Second Generation artists, who could build upon the work of those who had gone before.

And even more important, not many years passed before we began to get back actual images from space, taken by the probes and orbiters as they travelled between Earth and Moon, and even landed - or crashed - on the latter. These were followed in the seventies by images and data from Mars, Venus, and later even Jupiter, and in the eighties of Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. These were accompanied by a quantum leap in our knowledge about the Solar System and the universe. Let’s take a look at how this affected space artists.

Changing landscapes

Mars was always seen as the most Earth-like planet. It has polar caps and dark areas which appear to change with the seasons. Due to contrast with the reddish desert areas, these can appear greenish, so it was natural to assume that there could be vegetation, growing and spreading as the pole cap melts in spring.

Night launch of Discovery (Acrylics, 1995) a private commission

Night launch of Discovery (Acrylics, 1995) a private commission

Some astronomers, notably Percival Lowell, even believed that they saw ‘canals’, dug by intelligent inhabitants to irrigate the deserts. Through telescopic observations using spectroscopes Mars was known to have an atmosphere; therefore it must have a blue sky - right? Likewise Saturn’s huge moon Titan.

We are delighted to find that the Solar System has turned out to be a much more exciting and dynamic place than was once believed

Now the sky of Mars is orange-pink and glows down on craters and vast canyons instead of canals. Titan’s sky is also orange, and at least partly opaque, with clouds and an almost Earth-like landscape, but with seas and lakes not of water but of liquid hydrocarbons. Venus was long known to possess a dense, cloudy atmosphere which obscures its surface, so it could once be depicted with oceans of soda-water (because of the carbon dioxide in its atmosphere) or even with lush prehistoric jungles; or perhaps it was a wind-blown dust-desert, with rocks eroded into strange shapes? Now it is a blistering, hostile hell-planet, with massive shield volcanoes, sulphuric acid rain and lightning bolts.

Exploring Mars with mobile laboratory (Digital), from ‘Futures’

Exploring Mars with mobile laboratory (Digital), from ‘Futures’

It was believed that one side of Mercury always faced the Sun, so one side was bathed in the Stygian gloom of eternal night while the other roasted in the constant blaze of a huge Sun. Now it is cratered and remarkably Moon-like (Bonestell got this right), with a strange tide-locked rotation of 59 days and a year of 88.

Jupiter used to have 11 satellites, while Saturn, with nine, was the only planet - perhaps in the entire Universe - to be blessed with the unique phenomenon of rings. Today we know that all of the outer gas-giants possess such a halo, and their combined satellites number in the hundreds. But who could have forecast the active volcanoes of Io, the salty ocean below Europa’s icy crust, the giant ice ravines on Miranda, or the geysers of Triton and Enceladus? Officially, Pluto is no longer a planet but a ‘dwarf planet’, but this does not stop it from being one of the most interesting and perplexing bodies we have visited. Artists didn’t get it wrong; we can only work with the data that we’re given! And we are delighted to find that the Solar System has turned out to be a much more exciting and dynamic place than was once believed.

The IAAA

In June 1982 nine artists from the USA and Canada first came together on the volcanic island of Hawaii and formed the basis for the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA). A year later, 19 artists met in Death Valley, California, and as the word spread more artists, of both sexes, joined - not just from America but from Britain and many other countries.

Today there are around 120 members. Not all are realists, and some produce work which is impressionistic, expressionistic, abstract or surreal, but the majority (unlike science fiction and fantasy artists, who work almost purely from imagination) do have a background in astronomy, physics and mathematics, which enables them to interpret accurately the data from observatories and space probes, and convert them into believable scenes.

Sometimes, of course, they depict those very probes and satellites too (often working with NASA or space agency scientists) - for who is out there to photograph them? They paint in oils, acrylics, gouache and markers, use pens, pastels or coloured pencils, or the latest digital technology. Not all space artists are IAAA members, of course; but why do those who are travel sometimes thousands of miles to meet up with fellow artists and, often, competitors?

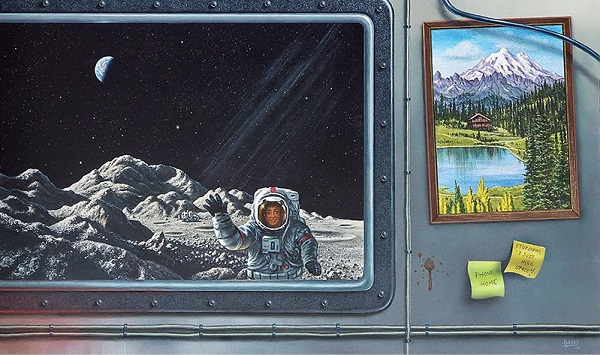

‘Two Worlds’ - my most recent ‘traditional’ painting. I wanted to show the ‘lived-in’ interior of a lunar base but also to contrast the bleak, monochrome lunar landscape with the blue skies, clouds, snowy mountains, lake and vegetation of our own Earth (Acrylics, 2015)

‘Two Worlds’ - my most recent ‘traditional’ painting. I wanted to show the ‘lived-in’ interior of a lunar base but also to contrast the bleak, monochrome lunar landscape with the blue skies, clouds, snowy mountains, lake and vegetation of our own Earth (Acrylics, 2015)

Speaking personally, after working as a ‘lone wolf’ since 1954 (the date of the first book I illustrated for Patrick Moore) it was almost like coming out of the closet when I finally met artists who were actually on the same wavelength. They hold critiques, exchange notes and tips - and have a lot of fun.

Most of them would dearly love to visit other worlds; even to take a trip into Earth orbit. Sadly, this is as yet impossible but they do the next-best thing. In 1988, a dozen Soviet artists met in Iceland with a similar number of US artists and one Brit (no prizes for guessing).

Other workshops have been held in Canyonlands, Utah, the Crimea, Yellowstone Park, the Grand Canyon and Meteor Crater, Arizona, and so on; nearly all ‘planetary analogues’. In a sense, they are following in the footsteps of the artists of the Hudson River School such as Frederic Church and Thomas Moran, who travelled with the pioneers who opened up the wild parts of America, enthralling the public with vast canvases of mountains, deserts and steaming thermal areas that seemed like the gates of Hell itself.

In deep space - the province of stars, nebulae and galaxies - even the Hubble Space Telescope and developments in terrestrial observing have not superseded but only provided much new material for space artists. Black holes, pulsars, quasars and hundreds of extrasolar planets; as each new space probe or satellite sends back its data, and each new discovery is made, artists review and revise their earlier renderings.

And they will continue to do so as humankind expands into space. Artists also have the advantage of being able to travel in time as well as space, because they can depict the beginning and the end of the universe, the birth of our Solar System, or the Earth and Moon - whatever takes their fancy. Despite the intrusion of the camera lens into the domain of artists, the paintbrush (or airbrush, or computer) will always be way ahead of it.

David A Hardy is a Fellow and European Vice President of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA) and is one of a handful of artists to have an asteroid named after them. His website is - www.astroart.org