As NASA ploughs ahead with returning to the Moon by 2024, a key aspect of the Artemis mission will be to bring something back with them - moon rocks. Lunar samples are worth their weight in gold and can provide a wealth of resources and information for both scientific and commercial purposes alike. But bringing these moon rocks back might be more problematic than it appears.

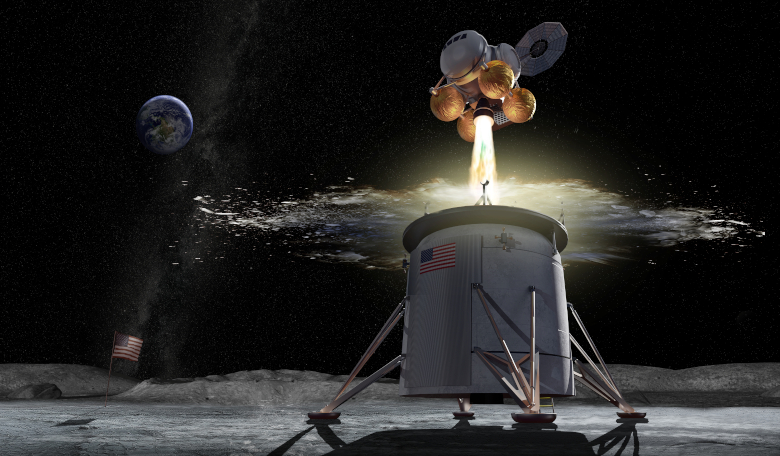

At the end of September, NASA announced that it was officially seeking proposals for human lunar landing systems designed and developed by American companies.

The agency had already issued two drafts over the summer giving many potential industry partners the chance to see NASA's requirements ahead of the official announcement.

Proposals to build a landing system are due today (1 Nov) - a timeline that even NASA states is ambitious. The first company to complete its lunar lander will be the one to land NASA astronauts on the moon in 2024, NASA officials said in a statement. Second place gets a 2025 mission, they added.

Initial drafts of the landing requirements for the first mission called for returning 100 kilograms of samples; this includes the mass of the sample containers. This was reduced in the final version however to 35 kilograms - 26 kilograms of samples and nine kilograms for the containers. Not a huge improvement on the samples returned by Apollo 11 during a single two-hour moonwalk, which totalled 22 kilograms.

This minimum amount or “threshold” landers is what landers have to be capable of carrying in order to qualify for the program, but according to Greg Chavers, deputy program manager for the Human Landing System at the Marshall Space Flight Center, the goal remains 100 kilograms; “we’ve clearly communicated to the companies that they will be evaluated more favourably on their ability to get to the 100 kilograms,” he said.

However, whether or not this payload can then be transferred to Earth in its entirety inside the Orion spacecraft is not so clear cut.

In presentations by NASA officials at the annual meeting of the Lunar Exploration and Analysis Group (LEAG) this week, eagle-eyed attendees spotted a small footnote on one particular slide that hinted Orion was not equipped to bring back the moon-rock payload NASA has asked for;

“Orion does not have specific storage to match the HLS [Human Landing System] sample return volume. Sample return mass to Earth via Orion might require mission-by-mission decisions on storage within Orion and possible considerations for different sample return container/bag design.”

In a separate presentation at LEAG, Chavers said of the issue; “Getting there quickly with technology we currently have, in 2024, was very challenging. We had no margin on the return mass.

“We haven’t conceded that it’s zero back on Orion yet, we just don’t know what the capability will be,” he added.

To get around this possible dilemma, Chavers said that alternative mechanisms for getting samples back, such as a robotic sample return vehicle delivered to the moon on a Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) lander, may need to be studied as a backup.

Not everyone was thrilled this latest development. During a discussion that followed Chavers’ presentation, Clive Neal, a lunar scientist at the University of Notre Dame said, “it’s getting very complicated.” It emphases the need to train astronauts “to bring the top quality ones back,” added Neal.

Eric Berger, Senior Space Editor at Ars Technica, took to Twitter to say; “The way to read this, I think, is that they have to negotiate this between the lander program and the Orion program. Probably not an issue, but it could be an issue. Right now they just don't have an answer on Orion rock capacity.”