Something weird is happening to oxygen levels on Mars and so far, all experiments to try and explain it are falling short of a conclusive answer, say scientists, who for the first time in the history of space exploration, have measured the seasonal changes in the gases that fill the air directly above the surface of Gale Crater on the Red Planet.

One of the jobs NASA's Curiosity rover is set to perform while it ambles around the martian surface is to inhale the air around Gale Crater with its Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument and analyse what its made of.

After a three year study – Mars years, not Earth. Three martian years equates to nearly six Earth years – SAM has deducted that Mar’s atmosphere is composed of: 95% by volume of carbon dioxide (CO2), 2.6% molecular nitrogen (N2), 1.9% argon (Ar), 0.16% molecular oxygen (O2), and 0.06% carbon monoxide (CO).

SAM’s analysis also reveals how this thin and wispy gas that stretches over this 154 kilometre wide depression, mixes and maintains the air pressure throughout the year as the seasons come and go.

In winter, CO2 freezes out over the poles. This lowers the air pressure across the planet as the other molecules redistribute themselves to maintain pressure equilibrium.

When CO2 is re-released from the polar caps as spring and summer returns, it mixes with the other gases to raise the air pressure again.

Nitrogen and argon also follow the pressure changes, but with a delay, indicating that transport of the atmosphere from pole to pole occurs on faster timescales than mixing of the constituent gases.

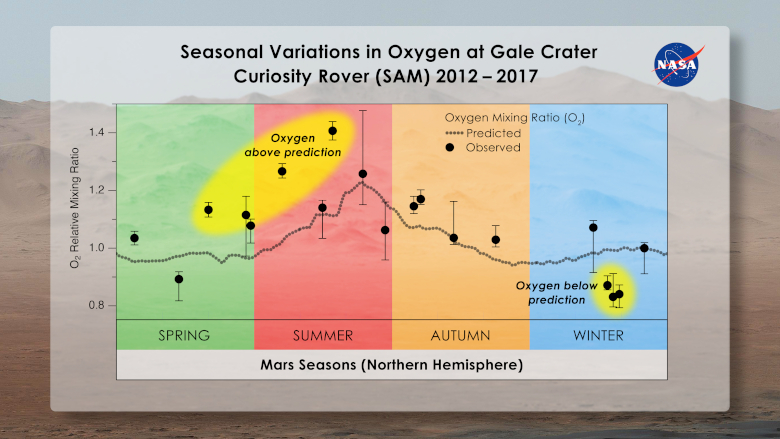

So far the patterns play out as predicted. Bizarrely though, scientists have found that one atom is not playing ball; oxygen. Oxygen should follow suit, but it isn’t.

Oxygen has been observed to show not only significant seasonal variability but also year‐to‐year variability, implying that something was producing it and then taking it away.

"The first time we saw that, it was just mind boggling," said Sushil Atreya, professor of climate and space sciences at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Atreya is a co-author of a paper on this topic published on 12 November in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

All manner of checks have been done to ascertain that it’s not an instrumental error at fault giving out dodgy readings; its not, SAM is doing just fine apparently. And chemical processes that maybe could account for what is going on don’t fit either;

What about the oxygen decrease? Could the Sun’s rays have split oxygen molecules into two atoms that then escaped into space? No, scientists concluded, since it would take at least 10 years for the oxygen to disappear through this process.

"We're struggling to explain this," said Melissa Trainer, a planetary scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland who led this research. "The fact that the oxygen behavior isn't perfectly repeatable every season makes us think that it's not an issue that has to do with atmospheric dynamics. It has to be some chemical source and sink that we can't yet account for."

But its not just oxygen that has scientists perplexed; methane (CH4) also spikes randomly and dramatically and increases in summer by about 60 percent for inexplicable reasons.

As the two gases appear to fluctuate in tandem, what's driving methane's natural seasonal variations may also be driving oxygen's cycle too.

"We're beginning to see this tantalising correlation between methane and oxygen for a good part of the Mars year," Atreya said. "I think there's something to it. I just don't have the answers yet. Nobody does."

Both of these organic molecules, oxygen and methane, can be produced from biological processes (i.e from microbes for instance) or through abiotic means (the weathering of rocks for example). All options are being considered, and although most people, if not all, would love the seasonal variations to be a by-product of living organisms at work, there is no convincing evidence of biological activity on our nearest planetary neighbour. Not yet anyway.

"We have not been able to come up with one process yet that produces the amount of oxygen we need, but we think it has to be something in the surface soil that changes seasonally because there aren't enough available oxygen atoms in the atmosphere to create the behavior we see," said Timothy McConnochie, assistant research scientist at the University of Maryland in College Park and another co-author of the paper.

There is still a lot of work ahead for the SAM team and Mars’ atmospheric gases will be continued to be monitored so that scientists can gather more detailed data throughout each season. In the meantime, Trainer and her team hope that other Mars’ experts will work to solve the oxygen mystery.

"This is the first time where we're seeing this interesting behavior over multiple years. We don't totally understand it," Trainer said. "For me, this is an open call to all the smart people out there who are interested in this: See what you can come up with."