Controversy over what constitutes a planet has rocked the planetary world ever since Pluto was down-graded to a dwarf-planet over a decade ago. While there were reasons for its demotion, the decision did not sit well with everyone. Now, new research suggests that the rationale behind this judgement is invalid and that Pluto should be reclassified as a planet again.

Pluto was discovered in 1930 by US astronomer Clyde Tombaugh and although everyone was quick to add this relatively small ball of rock and ice into the fold of existing planets in our Solar System, some astronomers began to question this course of action. They started to wonder whether this newcomer might instead be simply a wayward resident of a population of small, icy bodies that belong to the Kuiper belt; a ring of debris littered with objects of varying sizes that sit beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Later, discoveries of other Kuiper Belt Objects with masses roughly comparable to Pluto, such as Quaoar, Sedna and Eris, which actually appears to be larger than Pluto, helped push the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 2006 to relegate Pluto to the status of dwarf planet. Cue a reprint of posters and planetary textbooks around the world to reflect this seemingly harshly judged decision.

The verdict was also aided by an updated definition as to what makes an object a planet. The new guidelines, based on previously published scientific literature, specified that to be a fully-fledged planet then an object must "clear" its orbit, or in other words, be the largest gravitational force in its orbit. Unfortunately for Pluto, this was a double whammy as it shares it’s orbit with other Kuiper Belt objects.

However, in a new study published in the journal Icarus, UCF planetary scientist Philip Metzger, who has scoured over scientific papers from the past 200 years says that this standard for classifying planets is not supported in research literature; except for in one case. And that was back in 1802. And it was based on reasoning that has since been disproven.

"The IAU definition would say that the fundamental object of planetary science, the planet, is supposed to be a defined on the basis of a concept that nobody uses in their research. And it would leave out the second-most complex, interesting planet in our solar system,” Metzger said. "It's a sloppy definition.”

"We now have a list of well over 100 recent examples of planetary scientists using the word planet in a way that violates the IAU definition, but they are doing it because it's functionally useful," said Metzger.

Metzger implies that the IAU's definition is rather ambiguous as they don’t specify what they mean by clearing their orbit. “If you take that literally, then there are no planets, because no planet clears its orbit."

Co-author of the study, Kirby Runyon, another scientists who also feels that Pluto has been dealt with unfairly, suggests that the IAU's definition was indeed erroneous since the literature review showed that clearing orbit is not a standard that is used for distinguishing asteroids from planets, as the IAU claimed when crafting the 2006 definition of planets.

"We showed that this is a false historical claim," Runyon said. "It is therefore fallacious to apply the same reasoning to Pluto.”

So how should a planet be defined then? It should be based on its intrinsic properties, rather than ones that can change, such as the dynamics of a planet's orbit Metzger said.

"Dynamics are not constant, they are constantly changing. So, they are not the fundamental description of a body, they are just the occupation of a body at a current era,” he added.

Instead, a planet should be classified based on whether it is large enough for its gravity to allow it to become spherical in shape explains Metzger. "And that's not just an arbitrary definition. It turns out this is an important milestone in the evolution of a planetary body, because apparently when it happens, it initiates active geology in the body.”

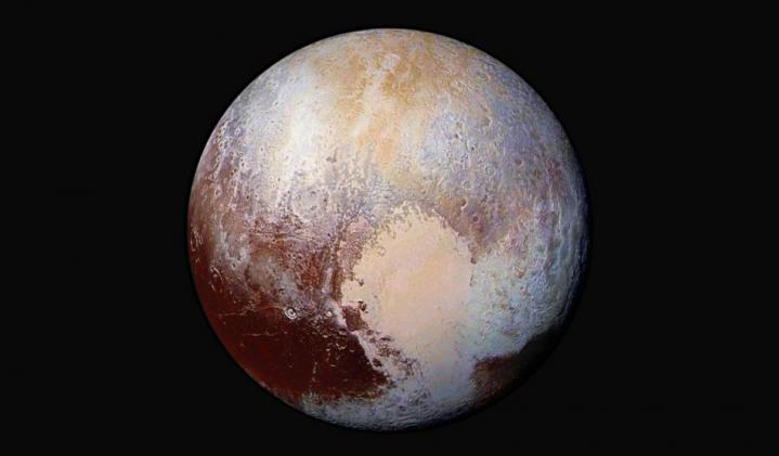

If this were the case, then Pluto would be right back up there with its bigger planetary neighbours as it has organic compounds, an underground ocean, evidence of ancient lakes, a multilayer atmosphere, and multiple moons. ”It's more dynamic and alive than Mars," Metzger said. "The only planet that has more complex geology is the Earth."