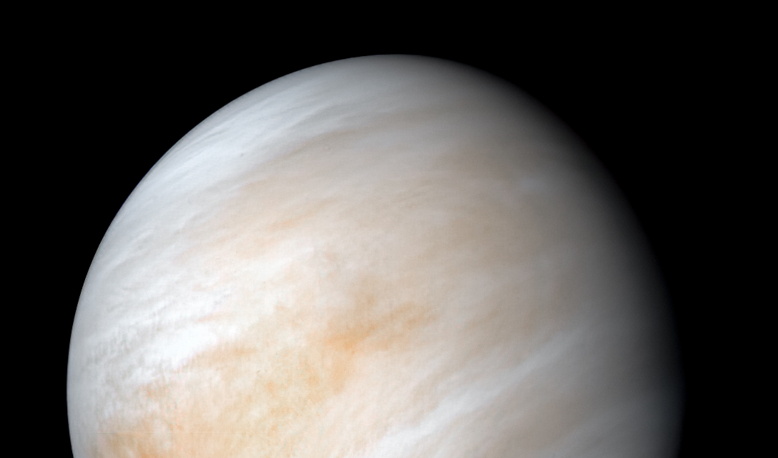

The search for life on our nearest planetary neighbour took an exciting turn last year when scientists found tantalising signs of phosphine – a gas that on Earth can only be produced artificially in a lab – in the clouds of Venus. Since then studies have either overturned the claim or added further intrigue to the finding.

But now, a new study measuring water concentration in Venus's atmosphere has concluded that life as we know it could not tolerate conditions among the planet’s sulphuric-laden clouds.

For life as we know it to exist, it needs water. Every cell on Earth is surrounded by a membrane and membranes are made from water. Without proper membrane structure, cells would be unable to keep important molecules inside the cell and harmful molecules outside the cell.

In order to help maintain shape and structure and to perform vital biological or chemical reaction, cells need energy and the available energy in a system is measured by a mechanism known as water activity.

Water activity is measured on a scale of 0 to 1, and laboratory studies have shown that life as we know it requires a water activity of at least 0.585 for metabolism and reproduction to take place, wherever a microbe might be hiding; be it a blisteringly hot habitat, or a freezing cold landscape.

But it seems that despite the ability of extremophiles to live in extreme environments, the thick, poisonous clouds of Venus are just too much as scientists now have a measure of water activity in the planet’s atmosphere and its not looking good.

That all important figure comes to below 0.004 – more than 100 times less than the limit for active life, says John Hallsworth at Queen’s University Belfast, and colleagues, in a new study published this week in Nature Astronomy.

It is so low because high concentrations of sulphuric acid – the bulk constituent of Venus’ clouds – reduce the water activity in the planet’s atmosphere.

"We bent over backwards to argue that the most extreme, tolerant microbes on Earth could potentially have activity on Venus," said Hallsworth at a press conference last Thursday.

But the parched skies of Venus have the equivalent to a relative humidity of 0.4 percent. “It's almost at the bottom of the scale, at an unbridgeable distance from what life requires to be active,” Hallsworth said.

However, there could be a silver lining of sorts. According to the team’s research, both Mars and Jupiter could have suitable levels for microbes to exist.

Water activity in Mars’s clouds is 0.537, which is slightly below the habitable range for life and similar to that of the stratosphere in Earth’s atmosphere.

Jupiter’s atmosphere on the other hand has a biologically permissive water activity of greater than 0.585 for temperatures between +10 °C and -40 °C. While this is within range, life could be hampered by factors such as “nutrient availability or high levels of radiation,” the team add.

Whats more, the team say that the approach used in this study can also be used to determine water activity in the atmospheres of planets beyond our Solar System. "The JWST will be able to determine atmospheric profiles of temperature, pressure and water abundance in exoplanet atmospheres," the authors write. As such it could be used to narrow down the search for extraterrestrial life.