The Hubble Space Telescope has given astronomers an unprecedented view of some of the Universe’s brightest infrared galaxies, allowing features as small as 100 light years or less across to be distinguished.

Only a few dozen of these bright infrared galaxies, which are as much as 10,000 times more luminous than our Milky Way, exist in the Universe and their properties may hold clues as to how galaxies formed billions of years ago.

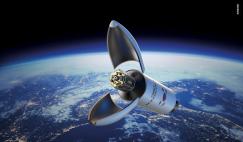

The galaxies were identified through a phenomenon called gravitational lensing, which occurs when the intense gravity of a massive object such as a galaxy or cluster of galaxies bends and magnifies the light of fainter, more distant background sources. Utilising this natural magnifying lens in space, Hubble has revealed what appears to be a tangled network of misshapen objects, but in reality is an attribute of the foreground lensing galaxies' gravity which is distorting the images of the distant galaxies.

"We have hit the jackpot of gravitational lenses," said lead researcher James Lowenthal of Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. "These ultra-luminous, massive, starburst galaxies are very rare. Gravitational lensing magnifies them so that you can see small details that otherwise are unimaginable.”

The results of the research indicate that the galaxies are veritable star-making factories, churning out more than 10, 000 new stars a year, at a time that corresponds with the peak of the Universe's stellar-birth boom more than 8 billion years ago. This frenzied activity has a knock-on effect as star formation creates lots of dust that enshrouds the host galaxies. While visible light is effectively blocked from our telescopes making it very difficult to detect them, the galaxies shine brightly in infrared light instead, so much so that they burn with the brilliance of 10 trillion to 100 trillion suns.

What is perplexing however, is that these young and distant ultra-bright galaxies are pushing out stars with a birth rate at 5,000 to 10,000 times higher than that of our Milky Way but with only the same amount of gas.

"We've known for two decades that some of the most luminous galaxies in the Universe are very dusty and massive, and they're undergoing bursts of star formation," Lowenthal said. "But they've been very hard to study because the dust makes them practically impossible to observe in visible light. They're also very rare: they don't appear in any of Hubble's deep-field surveys. They are in random parts of the sky that nobody's looked at before in detail. That's why finding that they are gravitationally lensed is so important."

One suggestion is that the material needed to make the stars is flooding into the faraway galaxies from another source. "The early universe was denser, so maybe gas is raining down on the galaxies, or they are fed by some sort of channel or conduit, which we have not figured out yet," Lowenthal said. "This is what theoreticians struggle with: How do you get all the gas into a galaxy fast enough to make it happen?"

As Lowenthal's team is only halfway through its Hubble survey of 22 galaxies, and with plans to use the Gemini Observatory in Hawaii in conjunction with these observations, the team can begin to ascertain the differences between the foreground and background galaxies to eventually provide a greater understanding of how these monster galaxies form.