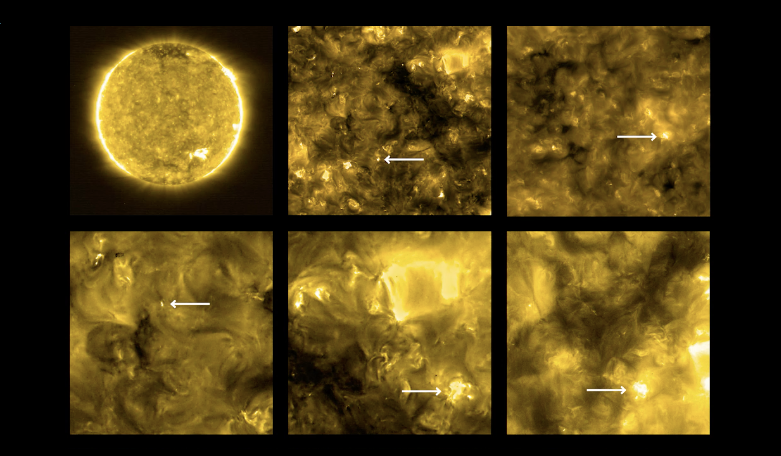

Positioned 77 million kilometres away from the Sun and only just out of its early phase of technical verification known as commissioning, the first pictures from ESA and NASA’s sun-watching spacecraft, Solar Orbiter, has wowed scientists by showing a new side to the sun not seen before.

In its first outing at observing the Sun, the Solar Orbiter spacecraft which was only launched in Feb this year, has revealed the presence of ubiquitous small fiery outbursts, dubbed ‘campfires’, near the surface of our closest star.

"The campfires we are talking about here are the little nephews of solar flares, at least a million, perhaps a billion times smaller," says David Berghmans of the Royal Observatory of Belgium (ROB).

Small however is a relative a term when it comes to describing phenomena on the Sun, as the campfires are at least the size of a European country, said mission scientists in a press conference yesterday.

The ‘campfires’ were detected with Solar Orbiter’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager, or EUI instrument, which takes high-resolution images of the lower layers of the Sun’s atmosphere, known as the solar corona. They are literally everywhere we look, added Berghmans who is the Principal Investigator of the EUI instrument.

The scientists do not know yet whether the campfires are just tiny versions of big flares known as nanoflares, or whether they are driven by different mechanisms.

But there is a good chance that these mini-explosions are behind one of the most mysterious phenomena scientists have yet to uncover about the Sun; why the solar corona, the outermost layer of the Sun’s atmosphere, is 300 times hotter than the Sun’s surface.

The solar corona extends millions of kilometres into outer space but bizarrely it is orders of magnitude hotter than the surface of the Sun, which is a ‘cool’ 5500 °C.

“These campfires are totally insignificant each by themselves, but summing up their effect all over the Sun, they might be the dominant contribution to the heating of the solar corona,” says Frédéric Auchère, principal investigator for SPICE operations at the Institute for Space Astrophysics in Orsay, France.

To know for sure, scientists need a more precise measurement of the campfires' temperature. Fortunately, another instrument on Solar Orbiter known as the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment, or SPICE instrument, does just that.

"So we're eagerly awaiting our next data set," Auchère says. "The hope is to detect nanoflares for sure and to quantify their role in coronal heating."

Solar Orbiter carries six imaging instruments, all of which study different aspects of the Sun and include along with SPICE, the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) and Solar and Heliospheric Imager (SoloHI).

SoloHI has also been instrumental in this early commissioning phase and has just helped the imaging team see a light so faint that the bright face of the Sun normally obscures it.

Known as so-called zodiacal light, this faint, eerie, cone-shaped white glow is visible in the night sky and appears to extend from the Sun's direction.

It is caused by light from the Sun reflecting off interplanetary dust and to see it, SoloHI had to reduce the Sun's light to one trillionth of its original brightness.

"The images produced such a perfect zodiacal light pattern, so clean," says Russell Howard of the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C, who leads the SoloHI team. "That gives us a lot of confidence that we will be able to see solar wind structures when we get closer to the Sun."

PHI on the other hand, which is designed to make high-resolution measurements of the magnetic field lines on the surface of the Sun, is helping the team monitor an active region seething with strong magnetic fields that has never been seen before by humans on Earth.

“Right now, we are in the part of the 11-year solar cycle when the Sun is very quiet,” says Sami Solanki, the director of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany, and PHI Principal Investigator.

“But because Solar Orbiter is at a different angle to the Sun than Earth, we could actually see one active region that wasn’t observable from Earth. That is a first. We have never been able to measure the magnetic field at the back of the Sun.”

Normally, the first images from a spacecraft confirm that the instruments are working, so not much is expected of them.

However the groundbreaking data returned by Solar Orbiter in its initial stages, has the mission team members clambering for more.

“Solar Orbiter has started a grand tour of the inner Solar System, and will get much closer to the Sun within less than two years. Ultimately, it will get as close as 42 million km, which is almost a quarter of the distance from Sun to Earth,” says Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter Project Scientist. “We are all really excited about these first images – but this is just the beginning.”