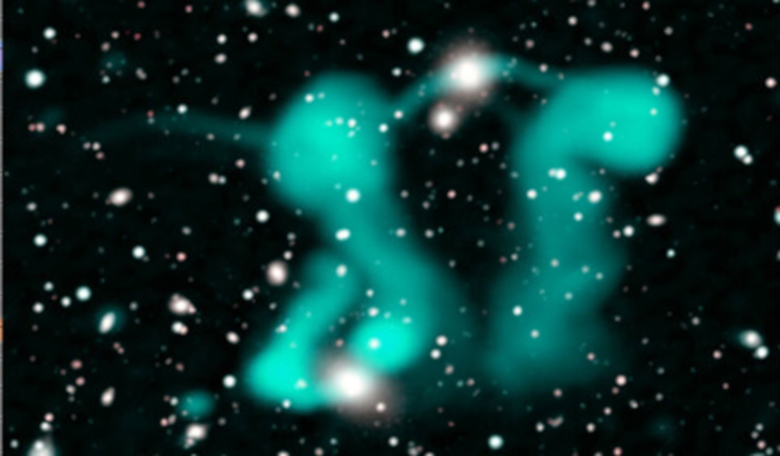

Astronomers collecting data as part of the first Pilot Survey of the EMU (Evolutionary Map of the Universe) project have discovered a number of new astronomical phenomena including a pair of "dancing ghosts" that have never been seen before.

Thought to be clouds of electrons surrounding galaxies about a billion light years away, the "dancing ghosts" baffled astronomers when first identified, says lead researcher Professor Ray Norris from Western Sydney University and CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation).

"When we first saw the 'dancing ghosts' we had no idea what they were,” Norris says.

After weeks of work, Norris and an international team of astronomers figured out they were seeing two 'host' galaxies, deep in the cosmos.

“In their centers are two supermassive black holes, squirting out jets of electrons that are then bent into grotesque shapes by an intergalactic wind,” Norris adds.

The team are not sure where the wind is coming from or why it is so tangled. Or indeed what is causing the streams of radio emission.

“It will probably take many more observations and modeling before we understand any of these things,” Norris says.

Along with the discovery of ORCs last year – mysterious Odd Radio Circles stretching nearly a million light years across – project team members have also found a giant radio galaxy, one of the largest known, whose existence had never even been suspected.

Whats more, its supermassive black hole is generating jets of electrons nearly 5 million light years long.

“ASKAP is the only telescope in the world that can see the total extent of this faint emission," Norris said.

The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope is one of the precursor instruments to the Square Kilometre Array, an international project to build the world’s largest radio telescope. The other will be built in South Africa.

ASKAP generates data at the rate of 100 trillion bits per second and consists of 36 ‘dish’ antennas that work together as one telescope. The antennas stand three storeys tall, each with a 12-metre-wide dish, and they are dotted across the outback over an area of about six square kilometres at the Murchison Radio Astronomy Observatory in Western Australia.

Australia will initially host more than 130,000 SKA antennas with an ultimate goal of expanding this up to a million antennas.

The primary goal of the EMU project is to make a deep radio continuum survey of the entire Southern Sky, extending as far North as +30 degrees beyond the Earth’s equatorial plane.

Once complete, it is expected to generate a catalogue of as many as 70 million galaxies.

In preparation for the full EMU survey, Norris and team are conducting the EMU Pilot Survey (EMU-PS) to test software and the survey strategy beforehand.

The EMU-PS will cover a smaller region in the sky and will incorporate an area covered by the Dark Energy Survey (DES).

DES, which is designed to probe the origin of the accelerating universe and help uncover the nature of dark energy, records data from the cosmos in visible light, whereas ASKAP is designed to look at much longer radio wavelengths.

By sharing data between the two projects, team members will be able to see if any object detected in radio waves has an optical counterpart and vice versa.

"We are getting used to surprises as we scan the skies as part of the EMU Project, and probe deeper into the Universe than any previous telescope,” Norris says. “When you boldly go where no telescope has gone before, you are likely to make new discoveries.”