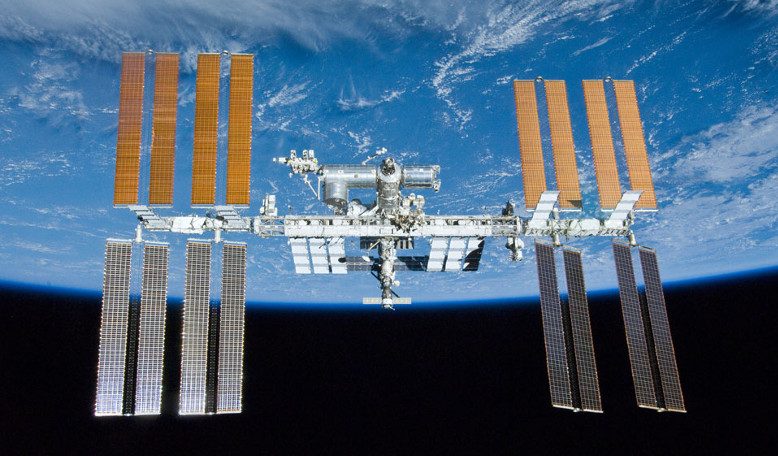

For the past 20 years, the International Space Station (ISS) has served as an off-world floating laboratory for inhabitants around the globe to learn what it means to live and work in space. But what now lies ahead for the permanently inhabited space outpost after a new audit report by NASA’s Inspector General pours scepticism on the practicalities of transferring the station’s operational running to commercial interests, if funding stops in a few years.

“Transitioning the ISS to private operation under the timetable currently envisioned presents significant challenges in stimulating private sector interest to take on an extremely costly and complex enterprise. Based on our audit work, we question the viability of NASA’s current plans, particularly with regard to the feasibility of fostering increased commercial activity in low Earth orbit on the timetable proposed..” the report says.

“Specifically, we question whether a sufficient business case exists under which private companies will be able to develop a self-sustaining and profit-making business independent of significant Federal funding within the next 6 years.”

Earlier this year, the Whitehouse reported that the Trump administration wants to end direct federal support for the ISS – which currently stands at around $3 to $4 billion per year – and instead shift the focus to commercial development of the station.

The decision is probably partly due to NASA’s interest in developing a human-tended lunar gateway that would orbit the moon. Any extension of the ISS past 2024 would therefore mean less (or no) money for the agency’s cislunar or deep space ambition, so naturally something has to give. And at this moment in time, it is the ISS which is looking increasingly likely to take the full financial loss.

But this does not mean that the US wants to scrap all affiliation with the station, it just doesn’t want to finance it anymore. US senators Ted Cruz, Bill Nelson, and Ed Markey have recently introduced the Space Frontier Act (S. 3277) to ensure that the US has continued access to low Earth Orbit and it plans to do this by extending the operation and utilisation of the ISS until 2030. However, how this will be achieved financially is unclear.

Maintaining the largest structure ever built in space is certainly a costly business, but since its completion, the ISS has provided researchers with the unique ability to study the effects of long-term exposure to microgravity and other extreme conditions, including space radiation; the effects of which can pose serious health risks to humans living and working long-term in space.

The ISS has been instrumental in identifying these risks, along with determining the technology gaps needed to ensure long-duration human spaceflight is possible and although NASA is currently positioned to complete most of its research in these areas, not all projects would be finished by the looming deadline of 2024.

“At least 6 of 20 human health risks that require the ISS for testing and 4 of 40 technology gaps will not be completed by the end of FY 2024 when funding for the Station’s operation is scheduled to end. In addition, research into 2 human health risks and 17 technology gaps is not scheduled to be completed until around 2024.”

If they are not completed within this timeframe, then what you may ask? “NASA may be forced to choose among a variety of options, including extending operation of the ISS past 2024, relying on alternate testing methods (i.e., non-space-based), or accepting higher levels of risk for future missions,” says the report.

The ISS is not purely a US endeavour however, as it shares the responsibilities of the station with Europe, Russia, Canada, and Japan. It is yet unclear which, if any, partners would be willing to sign on for an extension without an annual injection of cash from the States.