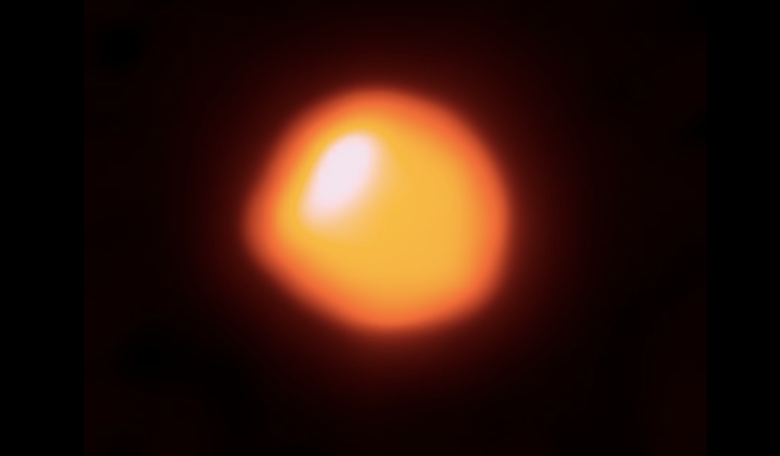

Stories are spreading that Betelgeuse, the red supergiant star which makes up the Hunter’s left shoulder in the constellation of Orion, is about to spectacularly outshine its neighbours as it detonates in a phenomenal explosion known as a supernova.

Betelgeuse ranks as one of the brightest stars in the sky and is one of the largest visible to the naked eye.

Its supergiant status already earmarks it as a variable-type star; a star that regularly brightens and dims with generally predictable frequency. In fact it is one of the most variable types of star of its kind, but even so, recently Betelgeuse has gone dim - much dimmer than expected of this luminous giant.

Its unusual behaviour has prompted some to speculate that Betelgeuse is on the verge of going supernova; a transformational rebirth event, that given the mass of the star (Betelgeuse is between 8 and 17 times as massive as our Sun and is about 120,000 times as luminous) means there is the possibility it could form a black hole after the explosion.

Most likely it will leave behind a neutron star that will eventually turn into a fast spinning star called a pulsar.

But still, the prospect of witnessing a supernova first hand and having telescopes ready to document the after-effects is very tantalising to those who study stars.

But just how possible is it that the star will explode anytime soon?

People have been observing Betelgeuse for as long as they have looked at the up at the skies. According to Chinese researchers, Chinese astronomers in the 1st century BC identified the prominent star as being yellow in colour. Was this a mistake, or was Betelgeuse at that time in a different stage of evolution? A yellow supergiant phase perhaps?

In the 19th century, British astronomer Sir John Herschel, noted many variations in Betegeuse’s brightness including a 10-year quiescent period that started in 1839. This had followed two episodes of excessive brightness from 1836 to 1840 and again in November 1839, where the star had outshone its constellation companion, Rigel.

Although Betelgeuse was the first star apart from our Sun to have its photosphere imaged, the red supergiant is cloaked in a cloud of dust and gas. Although dust shell makes observing the massive star difficult, it does indicates that Betelgeuse has been going through a period of mass loss and as such is no longer fusing hydrogen to helium in its core. Instead, hydrogen fusion is now occurring in a shell surrounding the core.

Eventually, the helium ash in the core will grow dense and hot enough to fuse helium into successive heavier elements until it reaches a runaway phase and the inward and outward forces in the core can no longer balance.

This life cycle is the same for all stars, large or small, but large stars live fast and die young. These same processes in a small star (like out Sun) would take billions of years to complete, but for a star like Betelgeuse, it would only take millions of years.

Has Betelgeuse finally reached the stage of no return? Miguel Montargès, an astrophysicist at Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, who studied Betelgeuse as part of this PhD, thinks not.

“In the coming days/weeks we expect the star to get brighter. Will it go supernova? Most probably not: models suggest it is a "young" red supergiant. But who knows? Our understanding remains partial,” said Montargès via Twitter.

Thought to be around eight to ten million years old, Betelgeuse is somewhere near the end of its life span, but how near no one knows for sure and it could still be as long as 100,000 years before the inevitable explosion occurs.

Emily Levesque, an astronomer at the University of Washington and an expert on the life cycles of red supergiants is equally cautious about the recent dimming of Betelgeuse. “We’ve never observed a star and said, ‘That star is going to die as a supernova,’ ” said Levesque. “That’s very much something we still need to learn.”

If it did happen soon, then you can rest assured that at around 670 light years away, the fallout from Betelgeuse going supernova will have no measurable effect on Earth.

The expanding shell of gas and dust that follows the explosion typically travels at around 10,000 kilometres per second (for comparison, the solar wind reaches around 450 kilometres/sec). This means it wouldn’t arrive at our planet until about 100,000 years after we see the star brightening.

The shell of material would be so spread out by the time it reached Earth that the only debris to envelope the planet would be tiny neutrinos, detectable with only the most sensitive scientific instruments. There would be no nearby nebula to swoon over or ghostly-looking aurora filling our skies. In short, the inhabitants of the planet 100,000 years from now would not notice any different.

“In any case, it is good to see that my favourite star triggers so much interest and we will continue to observe it,” says Montargès.