The launch market is divided into two sectors: government-ordered launches and the commercial sector. Government launches are known for monopolies of both launch providers and customers, as well as relative stability as far as business is concerned. Reconnaissance satellites, military communication satellites, weather monitoring satellites, navigation satellites, as well as research units, both manned and unmanned spacecraft: these launches are all commonly sponsored by governments. In this sector, high reliability and the ability to schedule an ironclad date for the launch are paramount. Costs are a secondary factor.

In this sector, only certified providers are usually allowed. The United Launch Alliance, for example, serviced most US government launches for a very long time. ULA is a joint venture of Boeing and Lockheed Martin, and uses Delta IV and Atlas V rockets.

Because SpaceX dramatically lowered prices, it was able to enter the commercial market, and to do so very aggressively, without having a statistical history of launches like its major competitors.

Until very recently, most US carriers served the government sector as opposed to the commercial sector because this was where the profits were.

In Russia, government launches are usually provided by the Centre for Operation of Ground- Based Space Infrastructure (usually abbreviated as TsENKI), which is owned by Russia’s Space Agency, Roscosmos, and the Russian Aerospace Defence Forces, together with developers and manufacturers of launch vehicles – Samara’s TsKBProgress (which famously developed the Soyuz-FG and Soyuz-U rockets) and Moscow’s Khrunichev State Research and Production Space Centre.

EU governments mostly use Arianespace and utilise the help of foreign providers in rare cases. For example, a few years ago the German SARLupe reconnaissance satellites, were launched via Russian Kosmos-3M rockets. In this particular T case, we can say that the costs of the launch played a part in the Europeans’ choice of a launch provider.

Breaking ground at the Falcon Heavy launch pad.

Breaking ground at the Falcon Heavy launch pad.

The market for commercial launches is more dependent on economic conditions. It has several providers and many different customers. Cheaper prices and high reliability are particularly important to this market. This market sector is also less exacting when it comes to launch dates.

Until recently, the commercial market was divided between several prominent players: Arianespace, International Launch Services (ILS), ULA, Sea Launch and Land Launch, all of which were oriented towards launching relatively large satellites to geostationary orbit. Meanwhile, Eurockot and Kosmotras specialized in launching light, low-orbit apparatuses on this market.

As already mentioned, ULA and Orbital Sciences Corp (commonly known as just Orbital and using Pegasus, Minotaur and Taurus rockets), practically did not service the commercial market, since that’s not where the big profits were. When they did do commercial launches, they were mainly serving other American companies.

Meanwhile, Indian, Chinese, and Japanese providers did not have a big presence on the commercial market.

The overall size of the launch market in 2013 was $5.4 billion, with the commercial segment representing $1.9 billion of that total sum. Profits on the commercial market were divided thus: $0.34 billion for the US $0.76 billion for Russia, $0.71 billion for the EU, and $0.1 billion for international organisations.

Major changes

The first major shake-up of the commercial segment came when Sea Launch went bankrupt. Due to a negative economic situation, an inability to provide a regular schedule of launches, as well as several disasters that caused customers to balk, Sea Launch ended up in a crisis and announced bankruptcy and Chapter 11 (as per US law) proceedings on June 22, 2009.

As we know from the paperwork, Sea Launch’s assets were valued around $100–$500 million, while its debts were valued from $500 million to $1 billion. Sea Launch emerged from bankruptcy in 2010, with Energia Overseas Ltd., a Russian company, as majority owner. Yet its financial woes continue; the Ukraine crisis has further caused the company to suspend operations until mid-2015.

At the same time, in 2010, SpaceX, headed by ambitious CEO Elon Musk, presented its Falcon 9 launch rocket to the market. This rocket was created as the result of SpaceX’s participation in the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program of deliveries to the ISS by commercial providers. The COTS program, announced by NASA in 2005, itself became a kind of revolution, because it brought a spirit of competition to the government sector.

A Russian Proton-M rocket being readied for ‘rolling out’ to the pad.

A Russian Proton-M rocket being readied for ‘rolling out’ to the pad.

Because SpaceX dramatically lowered prices, it was able to enter the commercial market, and to do so very aggressively, without having a statistical history of launches like its major competitors.

From 2010 until the end of 2014, SpaceX completed 13 missions. In 2015, it plans to complete an overall of 17 launches. In its launch manifest in the beginning of 2014, SpaceX listed a total of 41 missions. Only 12 of those missions are government-oriented (One order from the US Air Force, and 11 orders from NASA). One will be a test mission for Falcon Heavy – a heavy lift launch vehicle. The other 28 missions are being planned in the interests of commercial customers from various countries. A Falcon 9 launch currently costs $61.2 million, while a Falcon Heavy launch will cost $85 million. At this price, SpaceX launch vehicles are cheaper than most launch vehicles in their class.

SpaceX therefore has every chance to become the leader of the overall launch market, seriously encroaching upon both Arianespace and ILS territory. SpaceX was successful in betting on simple design solutions of the 1960s-1970s, while combining them with the most innovative manufacturing technologies. It also rejected complicated cooperation schemes, thus cutting spending on others’ expenses and profits.

But SpaceX’s main breakthrough will come if it manages to utilise the technology behind reusable rockets. If it can successfully do so, launch costs will go down several times and SpaceX will have an indisputable advantage on the market.

Even as it wants to conquer a great part of the commercial market, SpaceX also looks for profits in the government segment. The US Air Force plans to certify Falcon 9 in 2015, so that it can use the rocket to launch satellites in the interests of national security.

A serious challenge may originate via new Chinese, Indian, and Japanese launch vehicles.

SpaceX’s competitors, ULA chief among them, argue that government organisations should not rely on SpaceX due to the fact that the company doesn’t have a long statistical history of successful launches. Nevertheless, most Falcon 9 launches are successful.

There are other players besides SpaceX that are willing to transform the commercial launch market. Orbital – a competitor and a co-participator in COTS – is offering its medium-sized Antares launch vehicle as a comparatively low-cost alternative to NASA’s old “work horse,” the Delta II rocket. Yet the October 28, 2014 disaster and the consequent need to refine its technology means that Orbital is likely to be an outsider for the next two-three years or so.

Serious challenge

A serious challenge may originate via new Chinese, Indian, and Japanese launch vehicles. The Chinese CZ-7 medium class modular rockets, and the CZ-5 heavy class rockets, which are analogous to Delta IV and Atlas V respectively, are being finalised. If China can access the commercial launch market, it could compete with SpaceX as far as prices go.

Atlas V, the most in-demand rocket in the States (for now).

Atlas V, the most in-demand rocket in the States (for now).

India’s new GSLV MkIII rocket has similar capabilities to the Falcon 9 v.1.1, and could even be cheaper. Yet the frequency of launches is not great so far. The first launch of a fully completed vehicle will not occur until the end of 2015, or the beginning of 2016.

The challenge from Japan was unexpected. Insurers have already confirmed that the main Japanese launch vehicle, H-IIA, is reliable, while developers’ efforts could also result in a gradual price decrease of the launches. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has announced plans to cut launch costs by 50 percent by 2020, thus announcing a serious decision to enter the commercial launches market.

At the same time, ILS – the main provider of Proton-M rockets – could potentially lose a 15 percent share of the commercial market, going from 40 percent to 25 percent. The amount of commercial Proton-M launches has been decreasing since 2009, as offers by competitors grow in plentitude. The overall launch market is seeing tougher competition, and in order to stay in it, the Khrunichev Centre must take major steps in making production more effective, cutting its expenses, and solving issues of reliability.

Rising production costs and Proton-M launch failures, both government-sponsored and commercial, have helped out the Khrunichev Centre’s competitors.

The Soyuz rocket is comparable to the Falcon 9 v.1.1 as far as carrying capacity and cost. But this respectable Russian launch vehicle was designed all the way back in the 1950s and 60s, and its production costs continue to climb.

How the market is reacting

The arrival of new players on the scene has not gone unanswered. After much searching, the European Space Agency has settled on a look for its prospective launch vehicle, Ariane-6, which is meant to cater to the needs of both market sectors, as well as reflect the desire to retain the established cooperation between rocket developers – even if this cooperation may, in some cases, not be as economically effective.

…SpaceX’s main breakthrough will come if it manages to utilise the technology behind reusable rockets. If it can successfully do so, launch costs will go down several times and SpaceX will have an indisputable advantage on the market.

ULA is also ready to go head-to-head with SpaceX. At present, Atlas V is the most in-demand American launch vehicle (nine missions in 2014 alone). ULA plans to use growing demand from the Pentagon to develop more rockets, make them less costly, and re-enter the commercial market. In order to do that, ULA plans to introduce a new launch vehicle, Vulcan, to cater to both government and commercial customers.

Russia’s Angara-1.2 and Soyuz-1.2 lighter capacity rockets, which are beginning to be tested, may be a cheaper competitor to Vega (Europe), Taurus and Minotaur (US), and GSLV (India) – while being able to carry bigger loads. Yet the profits from launching smaller satellites are, right now, much lower than those from launching heavy geostationary satellites.

The newest heavy capacity Angara-A5 rocket, launched for the first time on 24 December 2014, can so far only be launched from Plesetsk, which limits its capabilities. A new launch pad on the Vostochny cosmodrome will not be completed until 2020. If the rocket proves itself to be statistically reliable, it may be later used for commercial launches. Until then, the Proton rockets are to serve the commercial market.

Considering new challenges on the market, Samara’s TsKB-Progress is researching the possibility of creating a new, modular launch vehicle, Soyuz-5, which could be an alternative to Soyuz-2, Zenit, and Angara-A5. Its main design features include a kind of technical simplicity, using liquefied natural gas as fuel, and greater effectiveness and flexibility, so that the rocket could be used to satisfy both commercial and state orders. Yet Soyuz-5 isn’t likely to make its debut before 2020.

Japan, meanwhile, has plans to create the H-III vehicle, with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries being the main contractor. This project is projected to cost $1.9 billion and take eight years to complete. Flight tests may begin in 2020. This rocket may be a direct competitor to Falcon 9.

What happens in a decade?

The main problem facing commercial launch providers is ambiguity surrounding prices offered by SpaceX and Chinese developers.

If the current, highly attractive SpaceX launch prices are not just a loss-leading lure aimed at poaching clients from more established providers (this is something that SpaceX’s competitors are claiming in unison), the market will be very different than what it was just five years ago.

Five years ago, rockets were developed with an eye to competitors’ well-known pricing politics, and nobody planned on major changes in the next 5-10 years.

Things have changed today – in order to set the correct parameters for your launch vehicle, one ought to know what kind of prices SpaceX will be offering in 2020. And this is something that nobody can know for sure. If SpaceX cannot master the technology required for reusable rockets, then other providers will have a fighting chance. If it does, almost all modern launch vehicles will be at a major disadvantage. This is why it is so hard to make concrete predictions.

What I can presuppose is that the commercial market will continue to be dominated by three companies. But Sea Launch will be supplanted by SpaceX with its Falcon 9. If it is successful, SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy will meanwhile be able to out-perform heavy capacity vehicles such as Ariane-5 and Proton-M. So, the Europeans’ and the Russians’ shares of the commercial market will steadily decline.

Later, around 2020, CZ-5/7 and H-III may join the scene. But these launch vehicles, just like GSLV MkIII, will not be able to capture a big slice of the commercial market and are likely to be used largely for government-sponsored launches. ULA rockets will likely meet a similar fate. After 2020, we may see Ariane-6 and Angara-A5 enter the market, but they will offer SpaceX only limited competition as far as pricing goes.

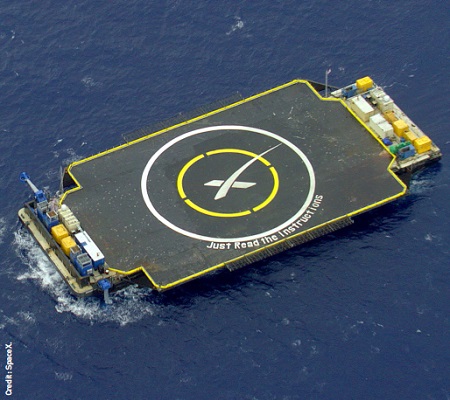

SpaceX have twice tried to land on a seabourne platform and failed. But the second time was closer than the first. Could the third time be the charm?

SpaceX have twice tried to land on a seabourne platform and failed. But the second time was closer than the first. Could the third time be the charm?

The U.S. government-sponsored launch market will be dominated by SpaceX and ULA. Orbital may plant its stake in the “lighter launches” category. In Russia, Europe, India, China and Japan, government-owned satellites will be launched by locally made rockets.

The good news is that the emergence of cheaper launch vehicles will open up space to more companies and organizations, and the overall number of launches will grow significantly.