A common objection to restorative justice is that without reference to external notions of proportionality, stakeholders could pursue excessively punitive responses. In other words, crews on long-duration missions could end up developing their own ‘ad hoc’ legal system, much like the apocryphal ‘wild west’ sheriff.

As many members of the space community have suggested, there is a need for the development of a robust conflict resolution system for long-duration interplanetary human spaceflight missions. Well-functioning relationships amongst crew members are vital for a successful mission – to the Moon, Mars or anywhere else. However, while pre-flight measures to minimise conflict such as careful crew selection are possible, the unpredictable and pioneering nature of interplanetary spaceflight means that it is difficult to foresee and eliminate conflict entirely.

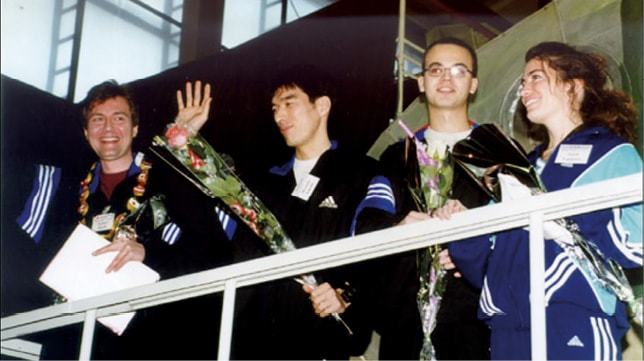

Analogue studies which seek to assess the psychological impact on humans of travel to Mars have shown varying levels of conflict, sometimes of a serious nature. For example, during the SFINCCS ‘99 study (an experiment simulating long-duration missions on the International Space Station (ISS) featuring crews of ‘astronauts’ from different countries), there was an allegation of sexual assault and a vicious fight between participants.

Conflict on a long-duration spaceflight, where crew members from different backgrounds and cultures live in close quarters for an extended period of time, could reduce their effectiveness or even completely destabilise the mission. So it is important that measures are put in place to resolve conflicts where they arise.

Conflict on the way to Mars

There is a need for the development of a robust conflict resolution system for long-duration interplanetary human spaceflight missions

Long-duration interplanetary missions differ in significant ways from current space activity, and may therefore require a different legal approach from Earth-orbiting missions. For example, distance-related signal delays will affect the quality of communications with Mission Control, as well as with family and friends, because real-time interaction will be impossible with anyone but other crew members.

The journey to Mars is likely to take around nine months, which is a considerable period of time to be living alongside a small group of people in close quarters, travelling an unprecedented distance from Earth. Opportunities to spend time alone, or to avoid another crew member who may be showing signs of psychological disturbance, or simply behaving in an irritating manner, will be minimal.

View from mission control into the habitat of the SIRIUS-19 four-month analogue mission that served as the crew’s spacecraft, lunar lander and home during their simulated journey to the Moon and back. Future SIRIUS missions will extend the duration to eight and eventually 12 months. In contrast to a simulated Moon mission, real-time contact with Ground Control will be impossible for Mars missions.

View from mission control into the habitat of the SIRIUS-19 four-month analogue mission that served as the crew’s spacecraft, lunar lander and home during their simulated journey to the Moon and back. Future SIRIUS missions will extend the duration to eight and eventually 12 months. In contrast to a simulated Moon mission, real-time contact with Ground Control will be impossible for Mars missions.

Analogue studies have given some indications of the psychological challenges that humans might face on a journey to Mars, and behavioural health risks have been identified as particularly difficult to mitigate. It is possible that these studies may even underestimate adverse psychological pressures, as they cannot adequately simulate being a long distance from Earth or the inability to return to Earth quickly (as from the ISS). It may well be, therefore, that conflict levels would be even greater than indicated in simulations.

Conflict in the special environment of interplanetary spaceflight could be catastrophic. The crew is likely to be small and everyone vital to the success of the mission (simply because there is little financial or practical scope for the inclusion of ‘back-up’ crew members). It will therefore not be an option to simply confine or separate a crew member whose behaviour becomes problematic.

Where conflict occurs, the solution must be focused on resolving the conflict and its causes, and reintegrating those who have contributed to the conflict. Importantly, this will need to be managed and implemented by the crew members themselves, as both the distance from Earth and communication delays would make it impractical to involve an external, Earth-based justice system in the process - even for serious conflicts. This does not, however, preclude the use of more traditional justice methods upon return to Earth.

Restorative justice

A promising model of conflict resolution that might work well in this context is the legal concept known as ‘restorative justice’. There are numerous varieties of restorative justice but the ‘empowerment-focused conferencing model’ is of most relevance here.

Members of the third crew of the 240-day SFINCCS ‘99 analogue mission, which was marred by an allegation of sexual assault and a vicious fight between participants.

Members of the third crew of the 240-day SFINCCS ‘99 analogue mission, which was marred by an allegation of sexual assault and a vicious fight between participants.

The basic concept is that, following a conflict, the stakeholders of that conflict (those most affected) come together to hold a restorative justice conference to discuss how best to resolve the conflict and move on. While the question of who ‘counts’ as a stakeholder can be an issue for restorative justice, in the context of interplanetary spaceflight, it is clear: all crew members are stakeholders.

Stakeholders, including the wrongdoer(s) themselves, must agree on how best to move forward following the conflict, and may consider issues such as how to restore harmonious relationships and how to reintegrate into the community anyone who has caused or contributed to the conflict. The stakeholders are empowered to decide for themselves how the conflict should be resolved, so they retain ‘ownership’ over the situation, and it is their values, considerations and needs that are prioritised.

The unpredictable and pioneering nature of interplanetary spaceflight means that it is difficult to foresee and eliminate conflict entirely

This is in contrast to a more traditional justice model, in which external values - external to the stakeholders and the situation - may take priority; for example, there may be prescribed methods of dealing with particular types of conflict, determined in advance of any situation.

Restorative justice is therefore more adaptable to the needs of particular individuals and particular circumstances. The fact that the wrongdoer participates fully, and must also agree to any outcome of the process before it is finalised, means that they have the opportunity to take responsibility for their actions and move on from the conflict. Studies have shown that offenders who participate in restorative processes are more likely to cooperate with the outcome and less likely to offend in future. The participation and feeling of ownership over the process and outcome are key factors in this regard.

Let’s consider a hypothetical case of wounding. Four months into a journey to Mars, crew member ‘A’ has been getting progressively more annoyed by crew member ‘B’s’ dreadful taste in humour and tendency to play irritating, sometimes slightly dangerous practical jokes. After a particularly unfunny incident, A snaps and lashes out with a sharp tool they happen to be holding, cutting B on the leg. The cut is relatively minor and A is immediately remorseful for the loss of temper. If this had occurred on Earth, in England, it could be charged as wounding, contrary to section 20 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861, and A would face a maximum sentence of five years in prison. If this had occurred on the ISS, jurisdictional issues would have to be determined, but if we assume both A and B to be English, then A could be returned to Earth for trial and face the same maximum sentence of five years (as per the ISS Intergovernmental Agreement, Article 22).

If such an incident were to occur during a mission to Mars, return to Earth to be dealt with by a terrestrial criminal justice system is clearly not an immediate option. It could still occur months later, but the friction caused by the conflict would need to be dealt with more urgently, to restore relationships amongst crew members to as great an extent as possible and to minimise the risk of jeopardising the mission.

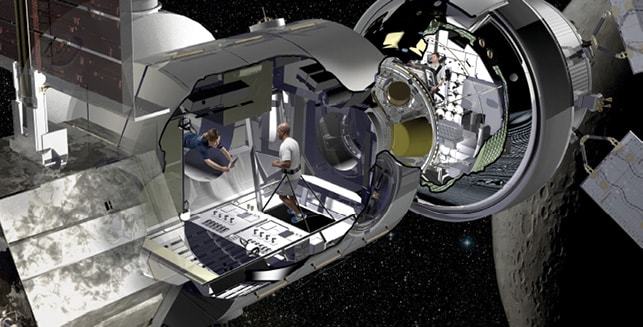

Living quarters concept for deep space missions of 30 to 60 days accommodating four crew members. At about 4.5 m wide and nearly 7 m long (the size of a small bus), the habitat may look roomy but it could feel very cramped after a few weeks.

Living quarters concept for deep space missions of 30 to 60 days accommodating four crew members. At about 4.5 m wide and nearly 7 m long (the size of a small bus), the habitat may look roomy but it could feel very cramped after a few weeks.

In this type of scenario, restorative justice would enable the crew members to work together, discussing the actions of both A and B and the context of those actions, to consider the best way of moving forward. This is likely to involve discussion of the various harms caused, to ensure both A and B understand the impact of their behaviour on other crew members. It may also mean working together to develop strategies to reduce levels of boredom for B, to reduce the likelihood of B pranking other crew members; and developing strategies to keep A’s temper under control and reduce stress.

Ultimately, it will be for those most connected to the offence to agree a suitable plan that can be implemented, and which fits the values and needs of the crew members at that particular point in the mission, in the particular novel environment in which they find themselves.

Limitations

A common objection to the use of restorative justice is that empowering stakeholders to decide on an appropriate response to conflict and wrongdoing, without reference to external notions of proportionality, could lead to excessively punitive responses. In other words, crews on long-duration missions could end up developing their own ‘ad hoc’ legal system, much like the apocryphal ‘wild west’ sheriff.

However, while crew members could in theory decide to implement whatever they all agreed to - which could include punitive measures - it is important to note that studies of restorative justice have shown that the process tends to reduce the retributive and punitive tendencies of participants. This may be because care is taken to consider all sides of what has happened, with an emphasis on context and ensuring everyone has a say in how to approach, manage and resolve the conflict.

Studies have shown that offenders who participate in restorative processes are more likely to cooperate with the outcome and less likely to offend in future

In addition, there are practical constraints on what is achievable to implement in the context of interplanetary spaceflight, where all crew members are important to the mission. This too is likely to guide participants towards less punitive measures that favour crew reintegration.

There are, of course, limitations to the effectiveness of restorative justice for conflict resolution on long-duration spaceflights. Firstly, it is not an effective fact-finding mechanism and therefore relies on admission of wrongdoing. Where no admissions have been made, it may be that the commander would need to decide what has occurred through speaking to crew members, perhaps with certain evidential safeguards in place. The commander would probably also need to be empowered to decide whether further action on return to Earth was necessary

SpaceX Starship approaching Mars - a journey to the red planet could take up to nine months.

SpaceX Starship approaching Mars - a journey to the red planet could take up to nine months.

Secondly, although the discussion may have highlighted useful elements concerning the context of what happened, agreement might not be reached following a restorative justice conference. That said, the special context of interplanetary spaceflight, where crew members have clear shared interests in the success and safety of the mission, may increase the likelihood of agreement.

Useful option

It would appear that restorative justice is a relatively low-cost, quick-to-implement conflict resolution mechanism that is particularly well-suited to the needs of interplanetary spaceflight. This is mainly because it avoids the risks of delaying conflict resolution until return to Earth or implementing some kind of complex long-distance justice system involving Earth-based lawyers and judges.

The main cost would come in the need to train all crew members in the subject, as all would need to be capable of taking on the role of facilitating a restorative justice conference. The importance of adequate training cannot be overstated, as restorative justice conducted incorrectly, and without a proper understanding, can be problematic and even harmful.

Restorative justice has an emphasis on context and ensuring everyone has a say in how to approach, manage and resolve the conflict, and the process tends to reduce the retributive and punitive tendencies of participants.

Restorative justice has an emphasis on context and ensuring everyone has a say in how to approach, manage and resolve the conflict, and the process tends to reduce the retributive and punitive tendencies of participants.

Fundamentally, restorative justice offers a method for resolving disputes that requires no external intervention, because the crew members are empowered to act autonomously. It encourages reintegration, which is important when no crew member is expendable and there is unlikely to be room on a spacecraft for confinement facilities. Even in the event that no disputes arise, the crew benefits from the security of knowing that an accessible system for resolving disputes is in place.

A mission to Mars will be challenging enough, thanks to the possibilities of equipment failure, microgravity effects and radiation exposure. Conflicts and disputes among the crew will only increase the challenge, so any mechanism for relieving this additional stress should be welcomed.

About the author

Dr Elizabeth Tiarks graduated from Durham University with a degree in philosophy, after which she studied law and qualified as a barrister. Alongside her practice in criminal and regulatory law, she completed an MA in philosophy and a PhD in law at Durham University. She is currently a senior lecturer in law at Northumbria University, with particular interests in philosophy of punishment, space law and cyberlaw.