UK government-commissioned Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) report released in 2014 highlighted airfields in Scotland, Wales and England that could potentially host a British spaceport and be in operation by the end of the decade. The eight potential spaceport locations – all on the coast – are Campbeltown Airport (Scotland), Glasgow Prestwick Airport (Scotland), Llanbedr Airport (Wales), Newquay Cornwall Airport (England), Kinloss Barracks (Scotland), RAF Leuchars (Scotland), RAF Lossiemouth (Scotland) and Stornorway Airport (Scotland).

The initial selection to qualify locations as suitable for a spaceport was based on a CAA assessment of a wide range of criteria from meteorological to environmental and economic factors. Criteria also included an existing runway that could be extended to over 3000 m in length; the ability to accommodate dedicated segregated airspace to manage flights safely; and a reasonable distance from densely populated areas in order to minimise impact on the uninvolved general public.

Spaceplanes are widely acknowledged as the most likely means of enabling commercial spaceflight experience flights - or as it is widely known ‘space tourism’ – in the near future. They also have the potential to transform the costs and flexibility of satellite launches, and the delivery of cargo and scientific payloads into orbit. If the target is met and specialist space operators begin flying from British shores, the country’s space industry as a whole could eventually be worth ?40 billion a year and provide 100,000 jobs.

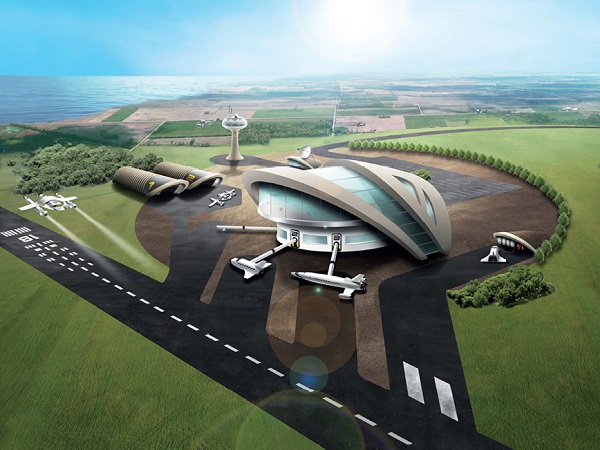

Impression of a potential UK spaceport

Impression of a potential UK spaceport

The CAA was also tasked to undertake a detailed review of what would be required – from an operational and regulatory perspective – to enable spaceplanes to operate from the UK. The review identified a wide range of potential obstacles but also recommended ways to overcome them.

One issue that current legislation does not fully address is the name ‘spaceplanes’. Both UK Department for Transport (DfT) and CAA legal experts classify spaceplanes as ‘aircraft’, meaning that the existing body of civil aviation safety regulation would apply to spaceplanes. But at this stage of their development commercial spaceplanes cannot comply with many of these regulations.

So, to enable spaceplane operations to start from the UK in the short term, the CAA has recommended that, under the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) Basic Regulation, sub-orbital spaceplanes be classified as ‘experimental aircraft’. This effectively takes them out of core civil aviation safety regulation and allows them to be regulated at a national level.

In addition, experimental aircraft are not normally permitted to conduct public transport operations, such as carrying paying participants for spaceflight experience. Given that this is the key goal of initial operations, the CAA says regulation could be possible under the Civil Aviation Act 1982 to issue exemptions and attach special conditions to the articles of the Air Navigation Order (ANO). However, it also says that spaceplane flight crew and participants would have to give informed consent in writing after being informed of the inherent risks in advance of any flight.

In the United States, spaceplane occupants will not be considered passengers in the traditional sense and the CAA says the UK should take a similar approach. Paying participants would have to acknowledge and accept that they will not benefit from the normal safeguards expected of public transport.

While all these steps would make it possible in legal and regulatory terms for commercial spaceplane operations to take place from the UK, there remains a clear risk. Whatever the standards of engineering and technical qualification, spaceplanes will not achieve the same safety standards as commercial aviation, and may never do so.

The CAA says that before allowing spaceplanes to operate from Brtain, the government must accept that such operations will carry a higher degree of risk than routine aviation activities. If this risk is acceptable, then protecting the uninvolved general public should become the highest safety priority consideration.

One of the most important factors in minimising any risk to the public at large will be the choice of the spaceport site. The CAA review details the different operational, safety, environmental and economic criteria involved in selecting a suitable launch site, and in doing so it recommends operations should start from an existing operational aerodrome and in an area of low population density, such as near the coast.

Different types of spaceplane could be launched from a site in the UK, ranging from air launch vehicles such as Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo to ground launch types embracing space tourist vehicles like the XCOR Lynx at one end of the scale and the UK’s Skylon at the other.

Among the first of the new crop is SpaceShipTwo, carried aloft on a WhiteKnightTwo turbo fan powered aircraft and likely to have marginal environmental impact and be the least problematical from a regulatory point of view.

Apart from integration and waiting facilities there would be relatively little required to adapt existing facilities to Virgin’s requirements. SpaceShipTwo’s unpowered descent and landing phase, however, might carry restrictions within the regulations set down by the CAA and the footprint reserved for the flight path would have to absorb potential down range and cross range errors that could result from technical failure or pilot error.

A well thought-out spaceport plan should also include a business park and an education centre. Most people like to think that a spaceport would create well-paid careers, improve the UK’s technological base, support and inspire our space sector and its next generation, benefit research and provide the positive feeling of returning us to a cutting-edge place in the world. For the region that secures the spaceport, it will act as a hub for some of the highest of high-tech industries and will inject a great deal into the local and national economy.

A potential flying candidate is XCOR Aerospace’s Lynx. The company continues to make steps towards commercial spaceflight and says its first flight could be during 2016. The Lynx is a two-seat, piloted space transport vehicle that will take people and payloads on a half-hour suborbital flight to 100 km and then return to a landing at the takeoff runway. Currently it is the only fully reusable suborbital spacecraft in pre-production.

Lynx propulsion is provided by four XR-5K18 rocket engines, each producing 12.9 kN (2900 lbf) vacuum thrust with kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants. Though it has a greater acoustic impact than SpaceShipTwo it is still relatively moderate compared to larger vehicles. It is designed to take off and accelerate to Mach 2 at an altitude of 42 km before a ballistic climb to an altitude of 107 km.

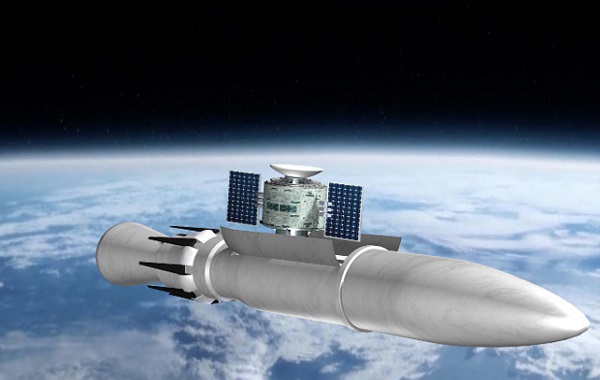

Artist impression of XCOR Lynx in orbit

Artist impression of XCOR Lynx in orbit

The space tourism market is unlikely to ever be large enough in commercial terms to justify adventure trips alone so all the major players are looking at the potentially lucrative prospects of using their craft for microgravity research flights as well. Virgin Galactic and XCOR both predict a future niche market for affordable microgravity flights carrying science and technology experiments on short periods of weightless flight.

Another potential spaceport user, though on an altogether different scale, is Reaction Engines’ Skylon spaceplane, currently being developed in the UK but unlikely to be flying much within the next 10 years. Skylon, capable of lifting a 15,000 kg payload to low Earth orbits, will require a more sophisticated kind of operating base to that of the sub-orbital spaceplanes. In fact, it is not really a spaceplane at all, but more of an aerospace vehicle capable of bridging the gap between air and space travel for the first time.

Powered by two Sabre engines delivering a combined take-off thrust of 2,700 kN and with a maximum loaded weight of 345,000 kilograms, the environmental impact will be considerable. It will be a noisy vehicle and may not so easily operate from a neighbourhood airport.

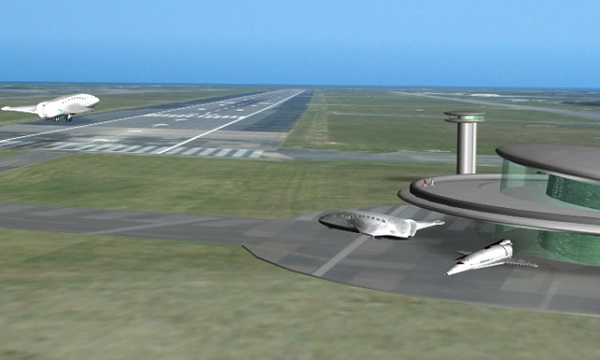

Newquay Airport in Cornwall

Newquay Airport in Cornwall

The application of Skylon is also very different from that of spaceplanes and it will need full payload processing and integration facilities in situ, as well as unique access requirements, which may be difficult at some of the named locations.

When it comes to selecting a spaceport location, those with long memories may think the UK has been here before. In the 1960s - when Britain had its own fledgeling space programme - Brancaster in North Norfolk was the main contender of three possible launch sites, the others being the Outer Hebrides and Woomera, Australia. The Outer Hebrides lost out because of poor accessibility and unpredictable weather and though Woomera seemed ideal it was obviously a long way from home. The preferred site was Brancaster.

Turning a daily or weekly launch schedule into a visitor attraction would be a good way to promote and pay for a spaceport

Turning a daily or weekly launch schedule into a visitor attraction would be a good way to promote and pay for a spaceport

Historian Nicholas Hill, who researched the thinking behind the Royal Aircraft Establishment’s apparently unlikely first choice, writes, ‘Brancaster was fairly close and it was convenient. If you launched from Norfolk then you had a clear run over the North Sea and over the polar icecap - and they thought this would be an ideal site.’

Brancaster was also relatively near Hatfield, Stevenage, and London, all important centres at the time in the British space industry, and yet it offered enough remote land for support equipment and buildings for launches of satellite-carrying rockets.

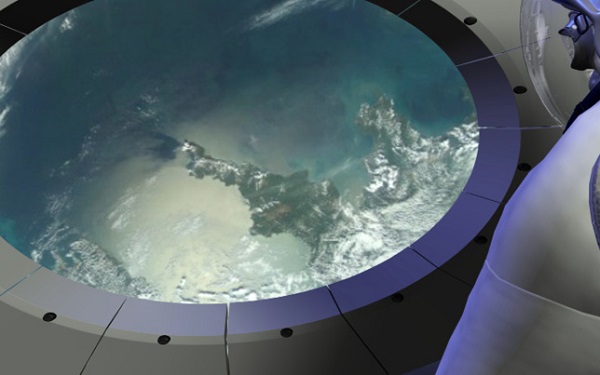

Views like this will be the preserve of the wealthy for some time to come

Views like this will be the preserve of the wealthy for some time to come

Of course, the Norfolk spaceport never happened. Each rocket would have most likely shed at least two stages during its ascent and, as oil rigs slowly spread across the North Sea, it was considered an unacceptable risk to launch rockets overhead. Britain’s space programme of the time, which included rockets such as Black Arrow, Black Knight and Blue Streak, was eventually switched to Australia - until the launcher project was axed in 1972.

The problem of oil rigs is not so acute for the modern spaceplane - which would not be discarding pieces during flight - and the government has stated that not being on the shortlist does not rule out the possibility of other sites being considered.

England’s only short-listed option is Newquay Cornwall Airport which has one of the longest (2,744 m) commercial runways in the UK and is home to Aerohub, the aerospace-focused Enterprise Zone which extends to 325 hectares and is the largest planning-free development site in the UK. Its location on the coast boasts uncongested and unrestricted airspace

The government must accept that such operations will carry a higher degree of risk than routine aviation activities

Glasgow Prestwick Airport, the Scottish government-owned strategic airport facility on the Ayrshire coast, is another possible location. Prestwick has a reputation as the UK’s foremost fog free airport and its micro-climate at the heart of the Ayrshire coastline meant that it was selected as the primary transatlantic ferry station for the thousands of US and Canadian built aircraft joining the Allied air campaign during WWII.

The same fair weather properties mean Prestwick today offers potentially excellent conditions for space launches, and the extensive airfield provides the facilities needed for the various types of re-usable spacecraft in development.

Small satellites and other payloads could be launched from spaceplanes more economically than from rockets

Small satellites and other payloads could be launched from spaceplanes more economically than from rockets

Prestwick has Scotland’s longest commercial runway (2,986 m) in service and is a strategic centre for search and rescue, freight operations and passenger services. With segregated spaceplane airspace a key requirement, its location sits outside of the congested south of England airspace sector dominated by inbound and outbound routings from major airports including Heathrow, Gatwick and Southampton, as well as routes into and out of major European hubs in Dublin, Paris and Madrid.

The offering from Wales is not insignificant either. The LLP 3 Runway at Llanbedr Airfield in the Snowdonia National Park is 2,414 m long and it boasts other impressive credentials too. It was once a dispersal airfield for Vulcan bombers during the Cold War and is near an active Danger Area (D201) operated and managed by Defence and Space Company QinetiQ.

From fully functioning communications satellites to smal cubeSats, business will be able to launch their equipment more frequently in future

From fully functioning communications satellites to smal cubeSats, business will be able to launch their equipment more frequently in future

Nearby MoD Aberporth offers unique radar and surveillance coverage over Cardigan bay, including high speed cameras and a Multiple Object Tracking Radar (MOTR) - of which only five exist in the world, the other four being in the United States. Rocket launches at Kennedy Space Center have been delayed in the past because the Welsh MOTR was not available.

Whichever location wins the day it is likely to be quite some time before we witness the first spaceplanes taking off in spectacular style from British soil with paying passengers on sub-orbital tourism flights. Spaceplanes flying from the UK will be largely owned and built abroad but there is no time to loose to secure a slice of the action because other European countries, like Sweden, are already promoting their own spaceport developments.

The UK government has shown foresight in planning to entice some of the early operators to the UK and the experience gained in the process may ultimately help pave the way for some of the much bigger and potentially game-changing vehicles of the future, such as Skylon.