As widely reported in various issues of ROOM, many current international space conferences cover the important topic of space sustainability, and space experts devote many hours to space debris mitigation or removal. Space professionals and some governments are eagerly looking towards technical solutions to this vexing issue, but without the enforcement of a regulatory authority, this threatens to become a never-ending saga.

No single country can tackle space debris mitigation alone and it requires the willingness of all spacefaring nations. It is a comparable challenge to that of mitigating climate change. For this reason, space scientists and other experts have called for a legally binding treaty to ensure that the ‘space junk’ caused by the burgeoning space industry doesn’t irreparably threaten activities in Earth orbit.

In 1958, shortly after the launching of the first artificial satellite, the UN General Assembly established an ad hoc Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), initially composed of 18 members. The committee was made a permanent body in 1959 with 24 members and now consists of 102 members, one of the largest committees of the UN.

In 1958, shortly after the launching of the first artificial satellite, the UN General Assembly established an ad hoc Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), initially composed of 18 members. The committee was made a permanent body in 1959 with 24 members and now consists of 102 members, one of the largest committees of the UN.

Regulating debris removal

UNCOPUOS has done a lot of work on many issues of space management, but it does not have the authority to make enforceable lawsUnited

There are two aspects to Active Debris Remediation/Removal (ADR). One is the technical and scientific side where there is a lot of work in progress. Many governments and private space entrepreneurs are actively looking for solutions to mitigate and remove debris, at least from low Earth orbit (LEO).

The other side to ADR is the setting up of a regulatory regime which will not only regulate future satellites, however small, against creating new debris in LEO, but also evolve regulatory and financial mechanisms to remove existing debris. Most of the larger debris is identified and belongs to specific states (over 90 percent of it to the US and Russia or the erstwhile Soviet Union); according to the Outer Space Treaty (OST) of 1967, it is their liability. Debris that cannot be identified is no-one’s liability, but needs to be removed as a collective action of the spacefaring nations.

It is clear that under the OST space is a ‘common heritage of mankind’ or ‘global commons’ and that every nation and every person has an equal right to travel and live in space or send a satellite, platform or any such system into space. As space becomes more democratic, the size and affordability of satellites has reduced and the cost of launch has come down. Under these circumstances it is essential to have a system of enforceable regulations that will bring orderly growth in which all can partake and be able to protect these vital assets.

Regulating body?

The United Nations consists of 193 sovereign member countries plus two non-sovereign states (The Vatican and Palestine). There are five UN treaties governing space activities but not all countries have ratified them and the number of ratifications differs for each treaty. So how do we manage the sustainability of space when all countries are not on board even within the existing space treaties. For effective and enforceable regulation we need the cooperation of all countries, so that the regulations are compulsorily included in the domestic legislation of each state and not only those states that have ratified the regulation.

For effective and enforceable regulation we need the cooperation of all countries

Under the umbrella of the United Nations there are two specialised agencies which come close to our requirements of regulating the skies and beyond: the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) - ICAO being better suited to make regulations for space activities because of the commonality in areas of operation. But what about the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA)?

UNOOSA was constituted as a part of the UN in 1958, 14 years after the formation of ICAO. Its purpose was to promote international cooperation in the peaceful use and exploration of space, and in the utilisation of space science and technology for sustainable economic and social development. The Office was established to assist and advise the ad hoc Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), which itself was established by the UN General Assembly to discuss the scientific and legal aspects of exploring and using outer space to benefit humankind. COPUOS became permanent in 1959, with 24 members. It now consists of 102 members, one of the largest committees of the UN.

Over time, COPUOS has done a lot of work on many issues of space management, but it does not have the authority to make enforceable laws. For example, it is limited to producing debris mitigation guidelines and requesting that member voluntarily follow them. So, while COPUOS has done a great job, the guidelines remain unenforceable.

Because of the growth in NewSpace and related activities in low Earth orbit, there is a need to integrate Air and Space Traffic Management, especially in airspace because of possible conflict.

Because of the growth in NewSpace and related activities in low Earth orbit, there is a need to integrate Air and Space Traffic Management, especially in airspace because of possible conflict.

ICAO, on the other hand, has made enforceable standards and, since it was formed in 1944, has seen a tremendous growth in civil aviation that is totally regulated and controlled. As a result, aviation is the safest form of travel in the world. Unfortunately, UNOOSA and COPUOS have a limited scope of operation and, since their formation, have not been able to regulate the growth in space traffic.

UNOOSA and COPUOS have a limited scope of operation and, since their formation, have not been able to regulate the growth in space traffic

As a result of the growth in NewSpace and related activities in low Earth orbit, a number of requirements have become evident:

- the need to integrate Air and Space Traffic Management, especially in airspace due to possible conflict

- the need for debris management/mitigation/ADR for both launch operations as well as defunct satellites.

- the need for much greater Space Situational Awareness (SSA) in order to avoid an unfortunate mishap

- the need for a better liability regime in space

- the need for new space debris remediation technology and its financing.

The question is: can ICAO manage to make sustainable regulation for commercial space or do we need a new space management organisation?

The International Civil Aviation Organisation has made enforceable standards and, since it was formed in 1944, has seen a tremendous growth in civil aviation that is totally regulated and controlled. If it took over the regulatory function for commercial space, work on establishing standards for commercial space activities could start with immediate effect.

The International Civil Aviation Organisation has made enforceable standards and, since it was formed in 1944, has seen a tremendous growth in civil aviation that is totally regulated and controlled. If it took over the regulatory function for commercial space, work on establishing standards for commercial space activities could start with immediate effect.

A new organisation?

The United States has, as recently as 31 October 2023, passed legislation on space debris called the Orbital Sustainability (ORBITS) Act of 2023. According to the US Chair of the Senate Commerce Committee, the Act is designed to “jumpstart the technology development needed to remove the most dangerous space junk before it knocks out a scientific satellite, threatens a NASA mission, or falls to the ground and hurts someone”.

This and other developments are well-intentioned and forward-looking in making space travel safe and sustainable. However, this is not a coordinated action at a time when there is a growing worldwide demand for commercial satellites by many countries and private companies. Space activities are no longer within the exclusive remit of a few states, so we need a multilateral institution that can lay down regulations or laws for all countries to follow.

In this context, one might consider setting up a new space organisation along the lines of ICAO, IMO or the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). It is, however, felt that there is little time left for setting up such a new space organisation, as it takes a lot of coordination, time and consensus building. It is also costlier to set up a new international organisation when all countries may not want to contribute. Furthermore, the interrelationship between air and space activities is so intertwined that the new organisation may not be able to develop without deep cooperation and coordination with the older organisations.

It is therefore suggested that in order to meet the immediate and urgent need for the fast-growing commercial space segment, which is largely restricted to LEO, ICAO should be requested and persuaded to make regulations for commercial space activities.

Layers of atmosphere.

Layers of atmosphere.

ICAO advantage

ICAO should be requested and persuaded to make regulations for commercial space activities

One of the driving reasons for suggesting ICAO as the regulatory body for space is the lack of a legal distinction between air and space.

The two main treaties governing aviation and space are the Chicago Convention of 1944 and the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. Surprisingly, although they are considered to be the fundamental treaties in each sphere, the former does not define or delimit the extent of airspace and the latter does not define the start of outer space. As it turns out this is a blessing in disguise, because the distinction between air and space is becoming blurred.

Currently, commercial aviation extends up to 35,000 to 45,000 feet (10.7 to 13.7 km), while space is widely considered to begin at 330,000 feet or 62 miles (100 km) above sea level, as proposed by Hungarian-American engineer and physicist Theodore von Kármán and known as the Kármán line.

The issue under consideration, however, is the distinction between airspace and outer space, as this distinction has no basis either legally or scientifically. In fact, it is one continuum which has already been divided by space experts into the following layers of the atmosphere: troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere and exosphere.

These artificial distinctions incorporate the various functions at specific heights in the atmosphere and there are three factors which can be considered for differentiating airspace from outer space. The first is the height beyond which a jet aircraft is unable to fly as the air is too thin; the second is where gravity causes a space object to re-enter; and the third is the level at which a space object tends to burn up unless it is well protected. But if we agree that the distinctions are artificial, there is no reason why one body should not be responsible for regulation.

ICAO has a streamlined system for making Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) in which all contracting members (the same as for the United Nations) are fully involved. The Council of ICAO which approves a Standard is an elected body of 36 member countries, elected once every three years by the General Body of ICAO. Hence there is full consensus. The Council is assisted by another elected body of experts called the Air Navigation Commission and there is, of course, the ICAO secretariat which is also a talent pool of professionals.

Work on establishing standards for commercial space activities could start with immediate effect, including active debris removal and standards for new LEO satellites that ensure atmospheric re-entry

In order to enhance the scope of ICAO in making SARPs for commercial space activities, some modifications will need to be brought about (both in the Annexes to the Chicago Convention and in the Secretariat of ICAO), but both can be done by the Council of ICAO. It is worth pointing out that once the Council approves a Standard, it becomes the law and does not require ratification by the General Body of ICAO.

However, while there need not be any immediate change in the Council membership, there will be a need for another Commission in parallel to the Air Navigation Commission which could be called, for example, the Space Navigation Commission. This committee of space experts would provide the necessary guidance and advice to the Council. Also, in the Secretariat of ICAO, appropriate additions will need to be made with, perhaps, a Director for Space Navigation, but with these minor changes ICAO could immediately take over the regulatory function for commercial space.

As a matter of fact, UNOOSA has developed many guidelines and the US government/Federal Aviation Authority, European Space Agency and others, have already made enforceable rules for space management for their nations’ space activities. UNOOSA’s guidelines and regulations will provide a useful input to the proposed ICAO Commission; indeed, a part of UNOOSA’s office could be absorbed by ICAO.

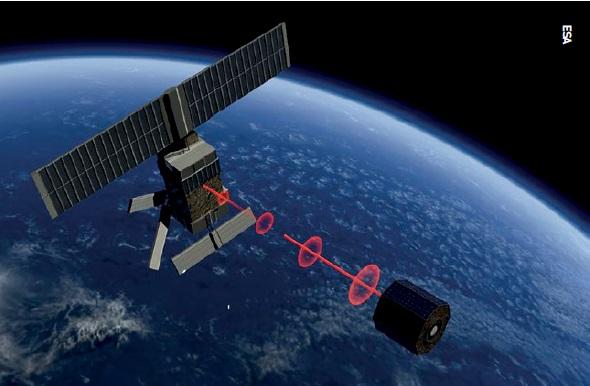

Active Debris Removal requires navigating in the close vicinity of the target. This might be achieved by Lidar means.

Active Debris Removal requires navigating in the close vicinity of the target. This might be achieved by Lidar means.

Near-term solution

All the new standards would automatically find their way into the national legislation of each member state as this is an ICAO obligation

If these suggestions are acceptable then work on establishing standards for commercial space activities could start with immediate effect, including active debris removal and standards for new LEO satellites that ensure atmospheric re-entry at end of life. The new ICAO could also start its work on an international consensus for debris remediation, in the way that it worked on the subject of aviation emissions and noise through its Committee on Aviation Environment Protection (CAEP). It is interesting to note that in the aviation sphere there were similar but unrelated issues of environmental damage by airlines and airports on the ground as well as in airspace; this was because of the emissions and noise by aircraft while taking off/landing and during flight.

All the new standards would automatically find their way into the national legislation of each member state as this is an ICAO obligation. ICAO also does a frequent audit of each country to ensure that its standards find their way into national legislation.

Another interesting feature of ICAO extending its jurisdiction to commercial space is that the Chicago Convention of 1944 has been ratified by all countries, in contrast to the five space treaties which have not been ratified by all. In fact, the space treaties do not have a high ratification rate and it varies from one treaty to the other, which makes the matter of enforcement very difficult, especially in terms of commercial liability disputes. Also, a weakness of UNOOSA’s Registration and Liability Conventions is that it is not compulsory for countries to register satellites on launching.

The goal of the UK Space Agency’s Clearing of the LEO Environment with Active Removal (CLEAR) Mission is to remove at least two UK-registered derelict objects from low Earth orbit (LEO). The Mission is intended to advance key technology building blocks and act as a catalyst for the development of commercially viable disposal services.

The goal of the UK Space Agency’s Clearing of the LEO Environment with Active Removal (CLEAR) Mission is to remove at least two UK-registered derelict objects from low Earth orbit (LEO). The Mission is intended to advance key technology building blocks and act as a catalyst for the development of commercially viable disposal services.

“If the Chicago Convention was extended to commercial space, these space conventions might not have much relevance for civil and commercial space activities except for guidance in space matters. Moreover, for issues of disputes and liabilities, the Montreal Convention of 1999 could be extended to commercial satellites, which would sort out the shortfalls in the Liability Convention in dealing with commercial satellites.

As commercial space becomes more popular, orbital debris is bound to grow. Furthermore, most new space LEO satellites and constellations have relatively short lifetimes - around five years due to rapid technological changes and cheaper cost - so the trend is towards quick replacements. There is therefore a greater need for regulation to make space safer. In the author’s opinion, the only and the best way to get out of this imbroglio is to give authority to ICAO to make binding regulations for commercial space activities.

About the author

Dr Sanat Kaul worked in India’s administrative service in the Ministry of Civil Aviation and was on the boards of Air India and the Airports Authority of India. As India’s Permanent Representative to the International Civil Aviation Organisation in Montreal, he is focused on the issue of the integration of Air and Near Space Traffic Management. Dr Kaul is Chairman of the International Foundation for Aviation Aerospace & Drones, and a member of the Parliament of Asgardia, the space nation. He is also on the Board of the International Association for Advancement of Space Safety (IAASS).