As Europe enters a defining phase of its space ambitions, the fifth European Space Forum unfolded in Brussels in July, just weeks after the European Commission launched its long-anticipated EU Space Act. This timing was no coincidence – it seemed to reflect an intentional moment of convergence between vision and legislation, between rhetoric and regulation. In a year that may well come to be seen as a turning point for Europe’s space future, the Forum offered a platform for policymakers, industry leaders and institutional actors to debate and align on the continent’s ambitions in orbit and beyond. The EU Space Act sets out to replace Europe’s fragmented approach to space governance with a harmonised framework that promises to increase competitiveness, enhance security and embed sustainability at the core of space operations. Against this backdrop, the Forum provided ROOM Space Journal with a firsthand insight into how Europe plans to redefine its role in the global space economy.

For years, Europe’s space sector has operated within a patchwork of national regulations, creating inefficiencies and barriers for cross-border cooperation. The EU Space Act aims to change this by establishing an internal market for space activities. Structured around three foundational pillars – safety, resilience and sustainability – the Act seeks to safeguard both space assets and the orbital environment, while promoting a fertile landscape for industrial growth.

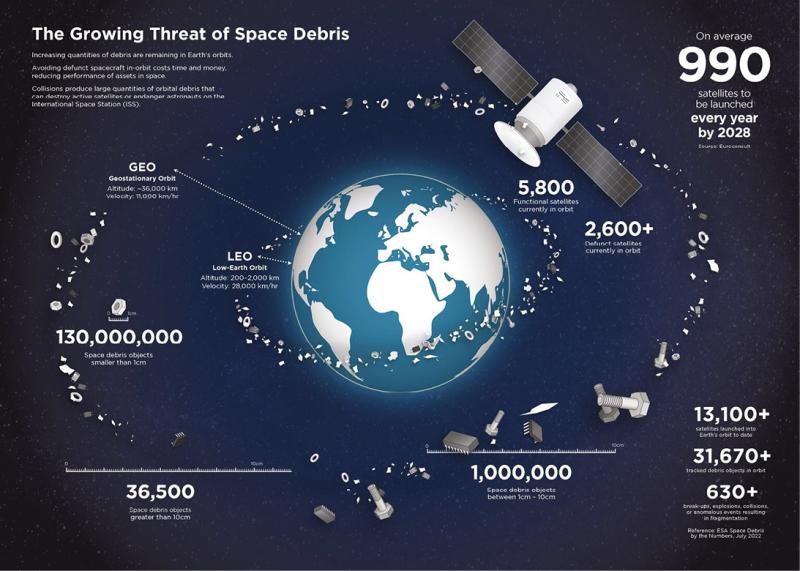

Safety is an increasingly urgent concern as low Earth orbit (LEO) becomes saturated with satellites and debris. With over 11,000 active satellites and projections of another 50,000 by 2035, the risk of catastrophic collisions is no longer theoretical. The Act mandates improved tracking of space objects and stricter end-of-life disposal standards, aligning EU policy with international norms.

Safety is an increasingly urgent concern as low Earth orbit becomes saturated with satellites and debris

Resilience addresses a different dimension of vulnerability – cyber threats and electronic interference. From satellite jamming to ground station breaches, threats to space infrastructure have grown in frequency and sophistication. The EU Space Act requires lifetime cybersecurity assessments and incident reporting, aiming to harden Europe’s orbital assets against both criminal and state-sponsored attacks.

The European Commission unveiled its long-awaited draft of the EU Space Act on 25 June 2025.

The European Commission unveiled its long-awaited draft of the EU Space Act on 25 June 2025.

The sustainability pillar reflects the EU’s broader climate goals. Space operators will be required to quantify and reduce their environmental impact, from launch emissions to orbital waste. Incentives for green technologies, such as in-orbit servicing, are designed to align economic innovation with ecological responsibility.

ESA strategy

While the EU Space Act provides the regulatory scaffolding, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) approach defines the technical and programmatic direction. The Agency’s evolving strategy was presented at the Forum by Eric Morel de Westgaver on behalf of ESA Director General Josef Aschbacher. Structured around ESA’s ‘Strategy 2040’, the presentation outlined how the upcoming Ministerial Council (CM25) in November will act as a watershed moment for Europe’s ambitions.

ESA’s five strategic goals – protecting the planet, exploring and discovering, strengthening autonomy and resilience, boosting competitiveness and inspiring Europe – will guide a proposed budget of €22.7 billion. This package includes next-generation Earth observation missions such as Space4Rail and the Digital Twin Earth initiative, designed to reinforce Europe’s global leadership in climate monitoring.

Delegates at the fifth European Space Forum.

Delegates at the fifth European Space Forum.

In the exploration domain, ESA plans to extend its footprint through initiatives like the ‘Terrae Novae’ programme, which includes the Argonaut lunar lander and new cargo return vehicles. These projects position Europe as a serious actor in the in-space economy and deep space logistics.

Launch capability remains a linchpin of sovereignty. ESA’s investments in Ariane 6, Vega-C, and the ongoing European Launcher Challenge are designed to restore reliable, independent access to orbit. In parallel, ESA’s ARTES programme and IRIS² constellation aim to provide secure, high-throughput communication networks for both civil and defence applications.

Perhaps the most ambitious proposal is the European Resilience from Space (ERS) initiative, a modular system designed to integrate Earth observation (EO), low Earth orbit (LEO) telemetry and navigation, and secure communications (IRIS2).

“No single member state can develop and maintain the full range of space infrastructure on its own,” de Westgaver noted. “Pooling resources allows Europe to respond to complex, fast-evolving threats with strategic autonomy.”

Vision and investment gaps

“We need coordination over duplication. Simplicity over complexity”

Giancarlo Granero, Head of Unit for Space Economy at the European Commission, reinforced the EU’s strategic outlook. With the global space economy forecast to reach US$1.63 trillion by 2045, Europe must mobilise its industrial base and academic excellence to secure a larger share, he urged. Currently, EU countries represent only 11 percent of global space investment, trailing far behind the United States (57 percent) and China (15 percent).

Granero identified three priorities – strengthening EU capacity, leveraging space across sectors like agriculture and climate, and capturing the in-space economy. Key initiatives include the CASSINI Accelerator (for startups), the Scala Investment Fund for manufacturing resilience, and new public procurement instruments designed to provide SMEs (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises) with market credibility.

Public-private synergy is at the heart of this vision. Space, said Granero, is no longer a niche domain but a critical enabler of economic growth and strategic autonomy. “The mission now is to turn this vision into reality,” he concluded.

Industry in transformation

From the private sector, Isabelle Mauro, Director General of GSOA, the non-profit Global Satellite Operator’s Association, offered a pragmatic yet optimistic view. She described a “satellite renaissance” driven by exploding demand for secure, ubiquitous connectivity and the convergence of terrestrial and non-terrestrial networks (NTNs).

Mauro emphasised that 96 percent of the world’s population may be covered by mobile networks, but those networks only represent 20 percent of the planet’s surface area. Satellites are increasingly vital for bridging digital divides, enabling services from education to precision agriculture in underserved regions.

She identified four trends transforming the sector: surging demand, rapid satellite innovation (including LEO and MEO advancements), cross-sector applications, and the integration of NTNs with 5G and beyond. She also welcomed the EU Space Act and Vision as “historic milestones,” but urged regulators to apply the guiding principles of proportionality, competition and consistency.

“Space safety, sustainability and resilience must be addressed by building on existing international standards,” she said. “We need coordination over duplication. Simplicity over complexity.”

Danish leadership

Space is increasingly intertwined with Europe’s strategic priorities

Frederik Pedersen, Space Councillor at the Danish Permanent Representation to the EU, and current chair of the Council’s Space Working Party, outlined the broad strategic goals of Denmark’s six-month EU Presidency which started in July.

He framed the Danish approach around the slogan “to focus Europe and protect the world”, reflecting the need for unity, competitiveness and resilience in a time of global instability.

Acknowledging a shifting international landscape shaped by “conflict, strategic competition and the legacy of Covid-19”, Pedersen emphasised the importance of European responsibility and self-reliance, particularly in areas like security and innovation. This included continued support for Ukraine, enhanced diplomatic engagement and efforts to secure Europe’s economic foundations.

For the space sector, Denmark sees strategic value in fostering a competitive European space industry that supports Europe’s open strategic autonomy and contributes to its green transition, digital transformation and security goals. “Satellites are a critical infrastructure,” Pedersen noted, “essential to numerous strategic functions”.

Ariane 6 completed its first flight on 9 July 2024.

Ariane 6 completed its first flight on 9 July 2024.

He confirmed that the newly launched EU Space Act would be a central focus for the Danish Presidency, with work centred on laying the groundwork for future negotiations. While final agreement during Denmark’s six-month term is unlikely, Pedersen stressed that the priority is “getting it right, not just getting it done quickly” – ensuring the emerging framework meets the needs of industry, member states and Europe’s long-term ambitions in space.

The Danish programme also includes key events designed to support the space agenda and technological innovation. These include a Presidential Space Conference in Malmö on 23 October – chosen as a model for sustainable urban development and emerging space entrepreneurship – and a joint conference with ESA and the European Space Policy Institute (ESPI) in Brussels focused on space security.

Pedersen’s emphasis on unity and long-term planning underscores the EU’s collaborative approach to space regulation, as member states prepare to engage with the Space Act’s legislative journey.

In conclusion, Pedersen highlighted that space is increasingly intertwined with Europe’s strategic priorities. “Technology is a key part of competitiveness and a key part of security,” he said. “We need stronger technology environments – for space, research and beyond – and that will be a defining theme of this presidency.”

Third country questions

The EU’s move signals a strong commitment to sustainability, safety and long-term governance – and a timely reminder that access to orbit increasingly comes with strings attachedESA

While the proposed EU Space Act was broadly welcomed by stakeholders within the bloc, its extraterritorial implications were also highlighted. One of the more pointed exchanges came during a panel on ‘Delivering Autonomy’, where a question was raised about the Act’s impact on post-Brexit UK operators, now classified as part of a “third country” under EU law.

Asked how the regulation might affect UK-based companies, UK government representative William Smith offered a measured response. “I think it’s very early days to comment,” he replied. “The UK Government doesn’t have a formal position yet. We acknowledge what [the Act] is trying to do and support any endeavour that is looking to make the orbital environment and space in general more secure, more resilient and safer. That is a collective good, undoubtedly.”

Smith emphasised the UK’s own approach: “The UK’s regulatory regime is an outcomes-based, agile regime, which works. It’s not perfect but we get good feedback from international stakeholders.”

While the EU’s draft legislation includes the potential to recognise third country regulatory regimes as equivalent, it provides no detail on how equivalence would be determined or negotiated. In the meantime, UK firms could face a dual compliance burden or barriers to market access unless a formal agreement is struck.

The proposed implementation date of 1 January 2030 offers a transitional window for dialogue and regulatory alignment. But as Smith’s comments underscored, ambiguity remains. “With no formal UK stance yet,” one delegate observed, “the industry remains in a holding pattern.”

Even so, the EU’s move signals a strong commitment to sustainability, safety and long-term governance – and a timely reminder that access to orbit increasingly comes with strings attached.

Focus on space sustainability

Providing an international perspective, Aarti Holla-Maini, Director of the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), highlighted the growing urgency of sustainability. Her remarks went far beyond orbital debris, touching on emerging challenges such as the environmental impact of re-entering debris particles, chemical residues in the mesosphere and even launch fallout affecting aviation.

“When we think about space sustainability, the mind goes immediately to space traffic, debris or spectrum interference,” she stated. “But there are deeper dimensions – from environmental consequences of launch vehicles to the rights and obligations related to debris landing on Earth. These are no longer hypothetical concerns – they are emerging policy challenges for a growing number of states.”

She highlighted growing cooperation with agencies like the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to address these broader implications, including initiatives addressing launch safety, ocean pollution and atmospheric emissions.

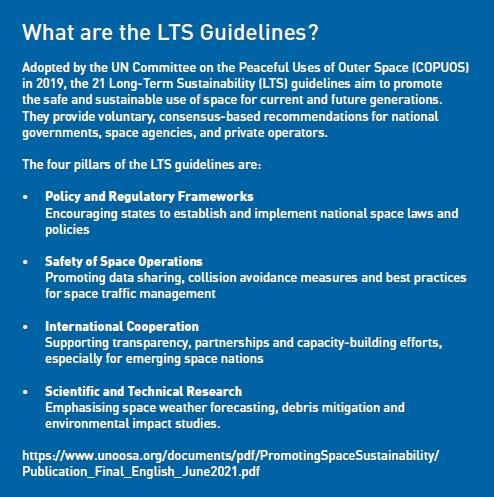

UNOOSA is leading efforts to implement its 21 Long-Term Sustainability Guidelines [see box] and improve compliance with the UN Registration Convention, which currently accounts for just 88.5 percent of space objects launched. A new expert group under COPUOS on Space Situational Awareness (SSA) will enable industry participation and global coordination for space traffic management.

“There is no margin for inaction. The treaties from the 1970s are not outdated – in fact they’re more relevant than ever. But they need support through modern implemen-tation”

In a striking anecdote, Holla-Maini recounted a recent near-collision involving a Malaysian satellite and a North Korean object, with a predicted miss distance of just 75 metres. “The satellite was not manoeuvrable. It was a real risk,” she stated. “And while disaster was averted, it underlined a troubling reality – national regulators are often left alone to deal with these incidents.”

Holla-Maini added: “We cannot clean up space like we can sometimes clean up Earth. There is no margin for inaction. The treaties from the 1970s are not outdated – in fact they’re more relevant than ever. But they need support through modern implementation.”

In closing, she issued a clear call: “The future of space is inextricably linked to how sustainably we use it. Europe has the innovation, the institutions and the global influence to lead by example – and UNOOSA stands ready to support that leadership.”

Turning vision into reality

The fifth European Space Forum and its 450 participants offered more than just aspirational rhetoric. It showcased a continent ready to consolidate its strengths, confront its weaknesses and articulate a cohesive vision for the future of space.

Between the EU Space Act and ESA’s Strategy 2040, Europe is aligning its regulatory, industrial and strategic levers to remain competitive in a rapidly evolving landscape. But as Frederik Pedersen reminded delegates, implementation matters more than speed and “Getting it right is more important than getting it fast”.

Europe now stands at the threshold of a new era in space governance – one that will be defined not just by the ambition of its vision, but by how boldly and precisely that vision is put into practice.

Aarti Holla-Maini, Director of the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA).

Aarti Holla-Maini, Director of the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA).

Frederic Pedersen, Space Councillor at the Danish Permanent Representation to the EU, and current chair of the Council’s Space Working Party.

Frederic Pedersen, Space Councillor at the Danish Permanent Representation to the EU, and current chair of the Council’s Space Working Party.